Local 600 Cinematographer Sonny Miller’s Legacy Washes Over the Industry in Waves of Talent and Respect. By David William McDonald. All photos Courtesy of David William McDonald.

Anyone who loves action cinematography – in the water, on concrete, or waist deep in snowy powder – already knows the legend that was Sonny Miller. Those who do not: I sincerely hope you will take the time to check out the provided Web links. They will help sustain the legacy of a union brother and true pioneer – a cinematic pirate of the seven seas who lived a life many only dream about.

We have a saying in the camera department that is often repeated when things get very stressful: “Hey, we’re still livin’ the dream!” I can say, as an admirer, student, and close friend of Sonny’s, he was one Guild cinematographer who lived that dream 24/7. Sonny radiated love, aloha, respect, and a desire to capture beautiful and thought-provoking images that would (and will) last a lifetime.

I’ll start at the beginning: Born Harold Miller in San Jose, California, on July 18, 1960, Sonny was given his nickname by his father, Bud, who remembers him as “the happiest baby” he’d ever seen. “Even as an infant,” Bud says, “Sonny was always calm, happy, smiling, cheerful. Some people are just born that way.”

In 1975, deep inside the “Brady Bunch” era, Sonny’s family relocated to North County, San Diego, where he grew up steps from the beach. He joined a crew of local skateboarders known as the “Down South Boys,” essentially the San Diego version of Stacy Peralta’s Dogtown crew, who were raising hell at roughly the same time 120 miles north in the Santa Monica/Venice Beach area. (Sonny shot some of the surfing scenes for The Lords of Dogtown feature decades later.) The late 1970s were the down-and-dirty days of skateboarding in drained pools and anywhere else concrete could be found, legal or illegal. A natural athlete, Sonny soon became a sponsored competitive skateboarder who counted himself among the pioneers of a sport that grew into a multi-billion-dollar industry.

One of the spots the Down South Boys found to skate was a place they called “Nuke Land,” the then-under-construction San Onofre nuclear power plant that offered giant culvert pipes as an early alternative to the half-pipe skate ramp. Sonny was also on his high school surf team and the surf team at local Palomar College, where he became a total “ripper” in the water, as well as on land. His love for photography began at an early age, taking a Super-8 class in junior high. By all accounts, Sonny seems to always have had a camera – motion or still – available to chronicle his friends’ adventures. This was, of course, long before the digital era of cell phone cameras and social media, when film required time and dedication, lab processing, and a great deal of exposure and lighting skill.

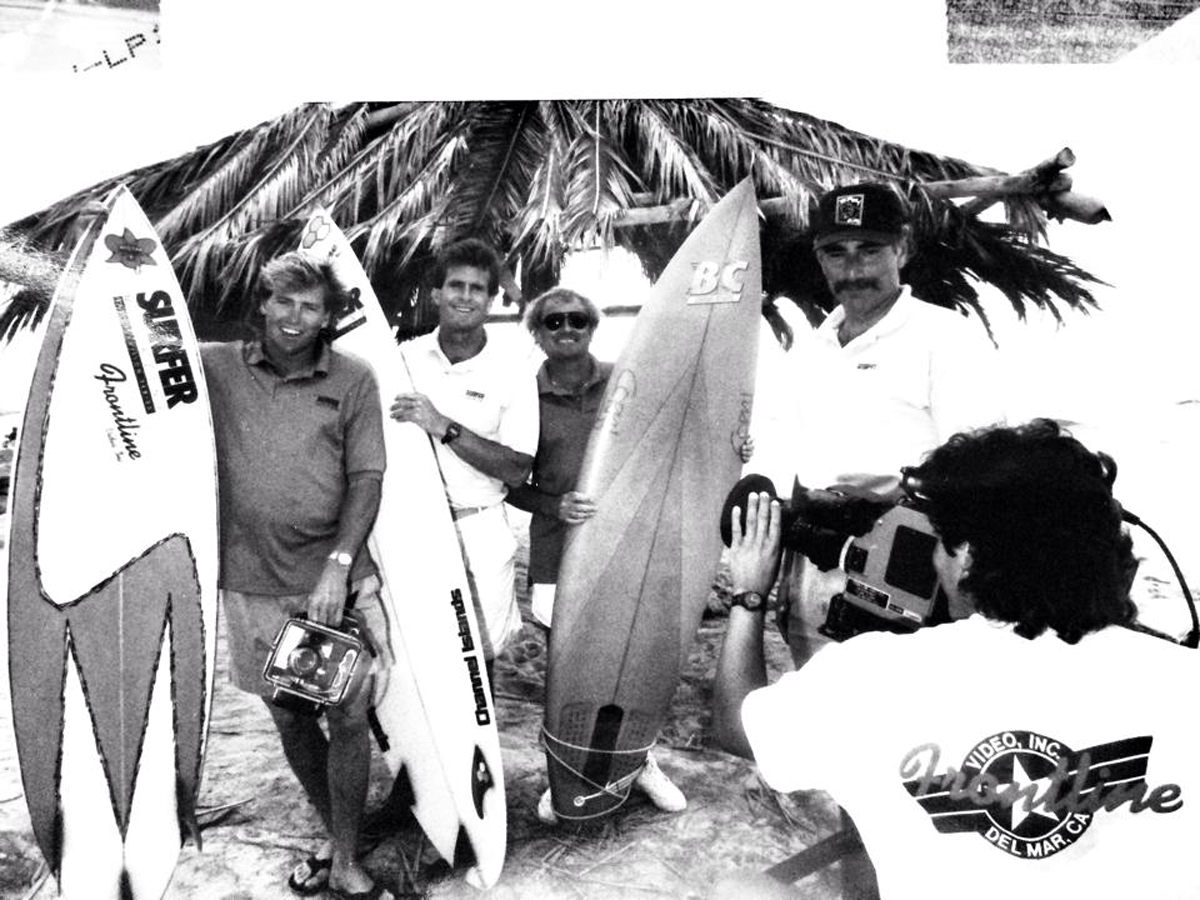

After delving deeper into photography at Palomar, Sonny landed a cover shot for Surfer Magazine, around 1984. He was one of the first photographers to use flash-fill lighting in a surf shot, and not just standard ambient light. As Sonny was naturally charismatic, with an infectious laugh and smile (his nickname was “Cap’n Fun”), and a fashion icon of sorts (for his crazy costumes), he made friends wherever his camera took him. While surfing a local spot in North County in the mid 80s, he met Ira Opper, an action-sports filmmaker producing a show for ESPN/Surfer Magazine. Ira felt Sonny was perfect for the role of on-camera host. But Sonny, who had begun to develop his own designed water housing for still and motion-picture cameras, was more interested in being “behind the lens for the show,” as Ira tells it, and so they agreed Sonny would do both.

The ESPN show, Hot Summer Nights, was broadcast nationally and featured Sonny alongside legendary pro surfer Corky Carroll. I remember taping the show on VHS in 1988, when I had moved back to Dallas (after living in Hawaii) and desperately needed a surfing fix. Other than the occasional contest on Wide World of Sports, Hot Summer Nights was all there was going for surf television.

Through the show, Sonny found a broader inside connection to the surf industry, as well as going out in bigger and better waves, and boat trips to unexplored surf destinations like Indonesia, Mexico, and South Africa. He gained access to pro surfers and visited “the seven-mile miracle,” the epicenter of competitive surfing located on the North Shore of Oahu, and the place that became the perfect canvas on which to paint his lifelong masterpiece.

When the 1990s dawned, Sonny had established himself as one of the top surfing photographers, both in and out of the water. Wetsuit manufacturer Rip Curl, based in Australia and one of the core brands behind the inception of professional surfing, contacted Sonny for a series of surf documentary films entitled The Search.

The documentary project would feature the company’s roster of sponsored professional surfers, most importantly, three-time world champ Tom Curren, who hailed from Santa Barbara, California. As the name hinted, the concept was to search for undiscovered surfing locations around the world. The series was directly influenced by Bruce Brown’s landmark 1966 documentary, The Endless Summer, which featured a laid-back V/O narrator (Brown) and two surfers hopscotching around the globe in search of the “perfect wave,” (which they found in South Africa). That low-fi, home-movie-type feature cost just $50,000 and to date has grossed more than $20 million!

Rip Curl’s “secret weapons” in this not-so-new idea of searching for the perfect wave were Curren’s eclectic taste in surf equipment and Sonny, who acted as director/producer and cinematographer. The pair travelled for years together, shooting The Search 1-5 and later the enigmatic Searching for Tom Curren, which documented the most innovative surfing sequences up to that time, thanks to Curren’s breathless talent and imagination in the water.

As athlete and cinematographer, Sonny and Tom developed a special relationship: Sonny had an uncanny talent for capturing Tom’s finest moments on film. He used Milliken 16-mm high-speed cameras and Arriflex 16-mm BL’s, all with his own custom-designed water housings. The Search series is still praised as some of the most innovative surf footage ever put on film.

Being part of a Union camera department, we are all well aware of what equipment is needed to capture the mood of a scene – on land. Sticks, hi-hat dollies, dollies on straight and curved track, gear heads, process trailers, arm cars, remote cranes, and speed tracking are all terms in our daily vocabulary.

But for a dedicated water shooter like Sonny, capturing an image meant hanging from the side of a helicopter over Waimea Bay – or riding next to a surfer on the back of a WaveRunner in treacherous wind and swell. Sonny would often swim in the break with the surfers (who were driving toward him at full speed), and then duck under at the last possible moment. His tools were swim fins, sunscreen, wave knowledge, and wetsuits (for colder water). He’d use surfboards as his dollies, boogie boards for handheld work, and always a heck of a lot of swimming ability. Sonny mastered all those techniques we use on land, but he’d often be high on a cliff with a super-long lens, or looking straight into the barrel of the wave from a tripod set up on the sand. He developed skills only a true “water man” would know how to safely incorporate into capturing moments that happen in a split second, in conditions controlled completely by Mother Nature.

In 1995, the ocean project to end all others, Water World, began principal photography in the Hawaiian Islands. One can only imagine how amazingly ambitious (and challenging) it must have been – up to 10 cameras in open ocean, all tricked-out in a variety of water housings, for days on end. The film became one of history’s most notorious box-office bombs, but it also began new careers for Hawaiian big-wave surfers in stunt work and water safety patrol.

I asked Local 600 water cinematographer Mike Prickett (Tunnel Vision, ICG May 2009) about Sonny’s interest in crossing over into the world of union feature films. He said Water World might have been one of Sonny’s first efforts, and possibly the movie that sparked his interest in joining Local 600.

In September 1998, Sonny did join the ICG and, in typical fashion, immediately found work as a camera operator and DP. His first big union show was the pilot for Wind on Water; the list of features and television series work he proceeded to compile in the last decade is impressive: In God’s Hands (1998); Die Another Day (2002); Blue Crush (2002), where he was also the voice of the contest announcer for the final scene at Pipeline; The Big Bounce (2004), Riding Giants (2004); Lords of Dogtown (2004); John From Cincinnati (2007); 48 Hours (2009); Law & Order (2010); The Hangover Part III (2012); Chasing Mavericks (2012); Ride (2013); The Westside (2013); and Point Break 2 (2014).

I met Sonny in Spring 2013, while working as an AC on a large ABC pilot called The Westside, directed by McG. The story was basically Dynasty goes to the beach – a wealthy surf industry mogul, his family, and the drama of a life spent in the water. Our gear list included a handful of ALEXAs, a Technocrane, a Steadicam, and lots of hand-held work, all on the sand in Venice, California. The budget was expansive, the days were long (14 hours) and the vibe was that we’d get picked up, no problem. (We didn’t.)

Sonny showed up early on day 6 of 17 at Topanga State Beach to shoot surfing sequences with former world champ Shaun Thompson, who was acting as a stunt double in the water. Land unit was in the middle of doing process trailer work on nearby Pacific Coast Highway. I had a bit of down time when Sonny showed up at the DIT station with several exposed RED EPIC cards for download and review. Of course, I had been a huge fan of his work for years.

I was nervous to break the ice, and I remember Sonny spoke first, in surfer talk: “Wow, it’s sure looks nice and glassy. Shame there’s not more swell in the water.” Translation: the ocean’s surface is very smooth, but the waves are too small!

I told him my name and mentioned I had done some Hydroflex (water housing) jobs for Billabong and Hurley with the Phantom camera system; I even got the chance to operate in the water on the Hurley shoot. This was a none-to-subtle hint that I would love working for him if one of his regular AC’s were not available. And I was also a surfer. The process trailer returned from running shots on PCH, and land unit was back to the grind, so I was unsure if I had made a connection. But just being able to tell all my surfer bros that I had met the legendary Sonny Miller, and that he was in my union, Local 600, was a thrill!

Later that same summer, work was slow and I was scanning Local 600–related social media pages for employment opportunities. I connected with Guild 1st AC Marcos Lopez, with whom I had worked before, and we lamented how much work had left L.A. for tax-incentive locations in other parts of the country. Because of this, Marcos was going off to work on a feature out of the country, making him unavailable for Ride, a surf movie shooting locally with cinematographer Sonny Miller. The film was written and directed by, and starred, Oscar-winning actress Helen Hunt.

Marcos asked about my experience using water housing rigs, and noted how Sonny’s were his own custom design and extremely functional, using mostly RED EPIC camera systems. Did I have any surf experience? Marcos wondered. That was the easy part: I’m in the water a lot (too much according to my wife and kids). Had I ever worked with Sonny? No, I said, but I had met him ever so briefly on The Westside.

As fate would have it, I got the job – but without any prep days at all. Fortunately, Sonny’s patience and mentorship abilities were as big as his talent. As the 2nd Unit DP for Ride’s water unit, Sonny walked me through the two water housings he’d brought onto the shoot. They featured a user-friendly, well-conceived design. The number-one rule with underwater camera systems (among many other rules) is not to flood them. You have to carefully tech your camera to ensure you have the proper lens filters and settings – ISO, color temperature, full battery and media, before your seal it up for action. As with any other camera department function, you have to be fast and effective, without rushing.

Most of the water action for Ride was shot in the shore break near the sand, except for two deep-water days when base camp was an equipment barge, along with support boats and a few WaveRunners. I had noticed very early the connection Sonny had with Helen Hunt while discussing the next setup, or the best angle to capture the scene, or just discussing what was available at craft service. Helen is, of course, a seasoned acting pro, but she had also become a surfer and avid stand-up paddle-boarder in recent years. She did many of her own surfing stunts in Ride, and she wore a full 3.2-mm wetsuit, in and out of the water, for 12 hours a day. (After four hours, a wetsuit becomes extremely uncomfortable.) On Ride we all saw that she was a true ocean warrior!

What was amazing about Sonny was how he would always find the best way to deliver Helen’s cinematic vision, which included lots of dialogue while floating on surfboards waiting for waves. Luke Wilson, who played opposite Helen as a surf instructor, thanked us all several times for the comfort level Sonny and the water safety team created in the water. Luke was particularly interested in Sonny’s adventures in Tahiti on a recent Roxy swimwear campaign; after shooting, he even invited the entire water unit out for food and drinks, and I think a big part of that was Sonny’s charisma and warm personality. Of course, Sonny was already a hero to me because of the images he brought back of pro surfers and working with personal idols, like Tom Curren. Now, seeing the way he interacted with A-list Hollywood talent was equally inspiring, and I felt lucky to be on his team.

Once my friendship and working relationship with Sonny Miller had officially been established, I felt blessed whenever the phone rang and it was Sonny calling. Over the next 12 months, before his sudden and untimely passing in July 2014, I helped him capture water imagery for jobs as diverse as Korean TV and network commercials. We bounced around ideas for a reality surf TV show, and I began looking to help him find a commercial agent. He would update me on professional surfing and how the ASP (Association of Surfing Professionals) Pro Tour was becoming big business: more cameras, technology, broadcasting venues and advertisement dollars meant, Sonny felt, more of a need to tie surfing in with big Hollywood features, TV and commercials.

Sonny had spent quite a bit of time in Hawaii and had accumulated a large group of friends and working relationships. When you spend a lot of time in Hawaii (I was there from 1986-1994), the food, culture, people, land, water and even the local lingo get into your blood. Sonny used Hawaiian terms often: aina, the land; mauka, inland (or drive toward the mountains); makai, drive toward the ocean; Haole, a Caucasian individual from the mainland; slippas, flip-flops; mahalo, thank you. The word Sonny used the most was ohana, or family. Hawaiian culture emphasizes that families are bound together and members must cooperate and remember one another.

Here is a social media post from Sonny (punctuation added), dated July 2, 2014, the day his mother passed away:

“Today is most likely the last day of an amazing journey with my mom. It’s a hard time at Relaxo [Sonny’s home in Escondido, CA], but I can only reflect on the life she made possible. Suzanne was diagnosed with dementia 7 years ago. She has been in our home all the time, and the Ohana is where she will pass. We never treated her as a patient but as a roommate and as my best friend. I want to extend thanx, love and appreciation to all my friends and family who helped us along the way. I give thanx to the animals we have who also enabled an unconditional love along our mission. I thank god for allowing her to stay as long as she has with us as a human and not a victim of the evil disease of dementia! You can’t win this battle. You have to make the best of it! That’s what we’ve done. She’s had a wonderful ride. Thank you for all the support love and kindness along the way. God Bless you Mom. Many more stories of my mom to follow she was the most adventurous mom you could have. I love you Mom!”

I noted earlier in this story how Sonny had the uncanny ability to solve problems with calm and composure. For the past seven years Sonny had been on the journey of caring for his mother in his own home, while she was slowly being taken from him. It speaks volumes about his character to have taken responsibility for this journey.

I waited a few days to call Sonny and offer my condolences. I knew this was a lot for him and there was also much family business to attend to. We spoke on the phone Saturday, July 5th. Death is such a tricky subject; you don’t want to say the wrong words or be disrespectful in any way. Sonny spoke in depth about it, even mentioning the possibility of a documentary project about his mother and their journey together.

Three days later, Tuesday, July 8th, was just a normal summer day in Southern California. My youngest son and I went to Malibu Surfrider Beach early to get some waves. I had begun to shoot GoPro footage of my son surfing – in the water, up close and personal, Sonny Miller style. I quickly discovered how really challenging it is to shoot in the ocean: wax on the lens, water droplets on all the best sequences, staying in position when my son grabbed a nice wave. Strangely enough, I ran into one of the producers from Ride in the water. He asked how Sonny was doing and mentioned he had heard about his mother. In an odd way, Sonny was with us, in the water, filming my son.

Later that same day, I received a phone call from a friend saying Sonny had passed away, and I did not, could not, believe it. It sounded like some kind of twisted joke. Sonny had passed? He was so full I life; I had just spoken to him. I began to have a panic attack, an adrenaline dump like I felt when I got rear-ended. I could not think straight and my knees were buckling. I called Sonny’s cell phone hoping he would answer, but the voicemail was full. I called a friend close to Sonny and learned the sad news. He was really gone.

Sonny Miller touched so many people, from so many different walks of life in so many different parts of the world. So it was fitting that subsequent celebrations of his life included so many around the globe. A first celebration was held on July 18, 2014 at the First United Methodist Church in Escondido, California. It was attended by close friends and family, filmmakers, Guild members, and, of course, pro surfing legends. Three weeks later, on August 10th, Helen Hunt and the producers of Ride planned a small memorial paddle out at Point Dume, near Zuma Beach. We moved out slowly into deep water, spread prayers and flowers, and talked about Sonny.

On October 26th, a large memorial paddle-out and scattering of Sonny’s ashes was held at Cardiff Seaside State Beach Park, in North County, San Diego, where Sonny grew up. Derek Hoffmann, fellow water man and Local 600 camera operator (Flash Frame, ICG, November 2014), coordinated an amazing event that was filled with articles of Sonny’s life: vintage cameras and housings; copies of Sonny’s films; his “onesie” snowboard outfit circa 1986; photographs of Sonny traveling the world; his swim fins, snorkel and mask; his bus; and the urn containing his ashes, which was one of Sonny’s former water housings. These items were all carefully assembled and displayed in what became a mobile museum of the life and accomplishments of a truly legendary surf cinematographer.

Once again, we paddled out into deep water, as flowers and prayers were spread around. Someone shouted: “It’s Miller Time!” Then big-wave legend Laird Hamilton said some words; Tom Curren was in the water with us, along with Derek and Local 600 water DP Mike Prickett. As Sonny’s ashes were released into the ocean, we all had the same feeling rushing through our hearts: Aloha and mahalo, brother! You were such an inspiration!

Links

Surfline/Jamie Brisick Tribute Article

http://www.surfline.com/surf-news/sonny-miller-1960-2014_111877/

California Memorial Paddle Out /10-26-14/ directed by Local 600 DP Ron Condon

Sonny Miller Films

https://www.youtube.com/user/SonnyMillerFilms

http://www.surfline.com/surf-news/what-is-a-waterman—-and-who-merits-the-moniker_47114/

The Search / Tom Curren Collection/ Jeffrey’s Bay

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oGDt18yECrY

http://deadline.com/2014/09/helen-hunts-ride-gets-screen-media-deal-831939/

Many terrific links about Sonny’s life and career available at:

SonnyMiller.com

Special Thanx:

Local 600 Members: Derek Hoffman, Mike Prickett, Don King, Larry Haynes, Marcos Lopez, Ron Condon, Chris Mosley, Bobby Settlemire, Sacha Riviere, Paul Santoni, Jas Shelton, Mike Brady, Chris Freeze, Erik Knutson, Scott Hubble, Phil Boston, Carl Hampte, The Crew from Point Break 2 – Water Unit, The Crew from Ride

Professional surfers: Tom Curren, Laird Hamilton, Brad Gerlach, Lisa Anderson, John John Florence, and Kelly Slater

Actors: Helen Hunt and Luke Wilson

ICG Executive Editor David Geffner

Eternal Watermen: Duke Kahanamoku and Jacques Cousteau