Andrew Dominik waited 14 years to get Blonde made; his new Netflix feature, shot by Chayse Irvin ASC, CSC, renders Hollywood’s most famous starlet from the inside out.

by Valentina Valentini / Photos by Matt Kennedy, SMPSP / Netflix

Seven months before Blonde was set to stream on Netflix when only a handful of people had seen writer/director Andrew Dominik’s three-hour, NC-17-rated adaptation of Joyce Carol Oates’ novel, which fictionalized aspects of Marilyn Monroe’s life, the writer/director told a trade magazine that it was a masterpiece.

“Blonde is the best movie in the world right now,” Dominik opined. And now, chatting with Dominik over Zoom (as the film’s Venice Film Festival world premiere nears), he doesn’t back down from that comment. Instead, Dominik qualifies it: “I know [saying] something like that is inviting people to disagree with you, but why bother making a movie if you don’t feel like it could be one of the best movies of all time?”

Why indeed? Joyce Carol Oates saw a rough cut of the film in 2020 and described it as a “brilliant… feminist interpretation” of her book, so it’s safe to say Dominik has one true fan in the source material’s creator. Of course, the New Zealand-born Australian filmmaker is no stranger to book-to-screen adaptations – there was the 2007 Oscar-nominated The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford and the 2012 neo-noir crime thriller Killing Them Softly. But since writing the script for Blonde in 2008, eight years after Oates’ book swept the nation’s bestseller lists, Dominik’s been struggling to get the project made. With the controversial casting of Cuban actress Ana de Armas as the translucent, busty beauty, and the visceral intimacy of the storyline on screen, Blonde will, like Monroe herself, be a conversation point, regardless of critical opinion. I asked Dominik about the long slog to get Blonde produced, why he chose Director of Photography Chayse Irvin, ASC, CSC as his right-hand man, and what his goal was in transposing Oates book to the small screen.

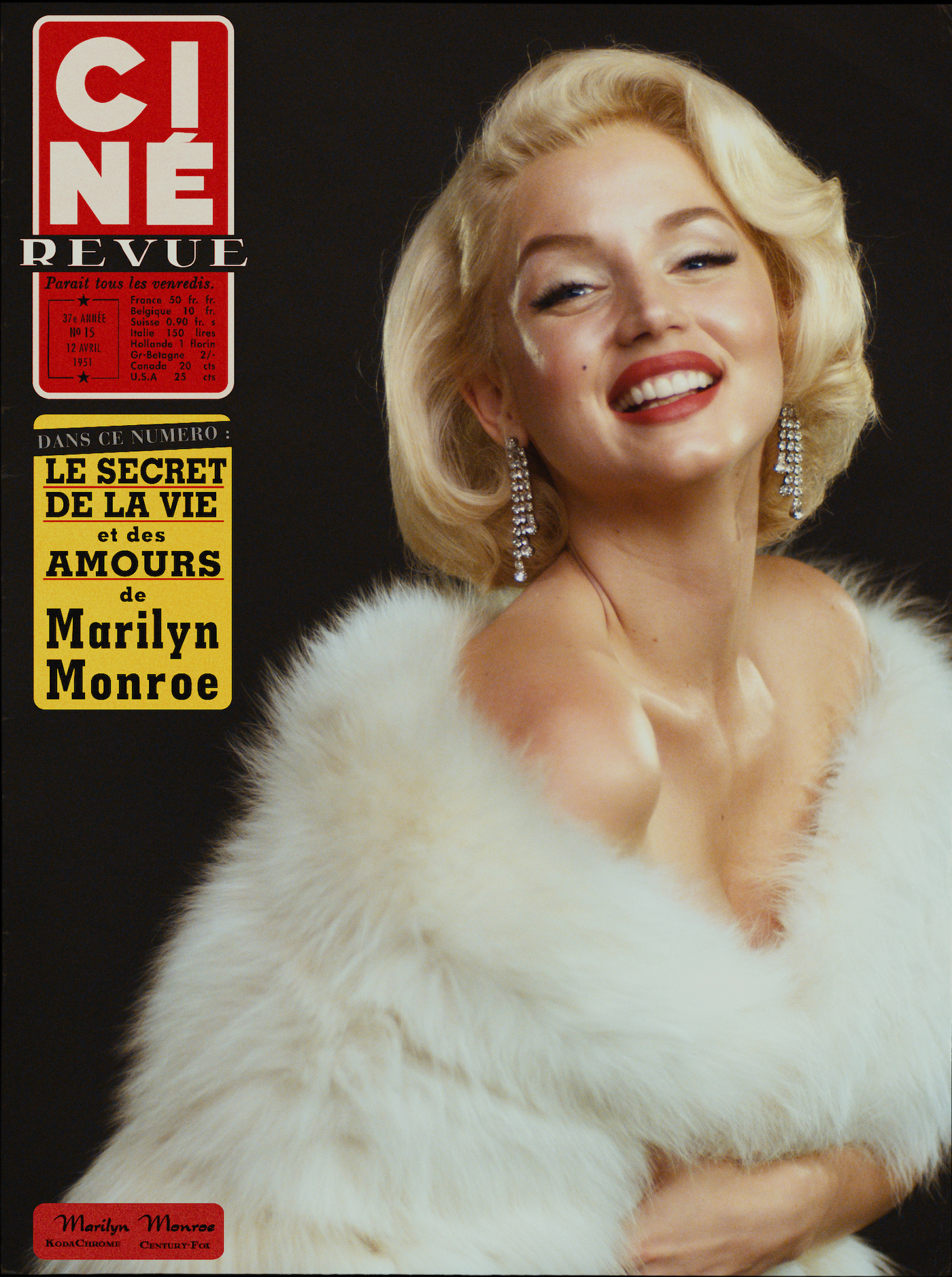

ICG: Did you always have a clear path toward how to come at this story visually? Andrew Dominik: I did. The big visual idea was to sort of traffic in the collective unconscious of Marilyn Monroe. There are so many images of her, and it seemed exciting to me to be trafficking in these big, familiar cultural images.

When Netflix finally picked up the film in 2016 and you began to think about a DP – two years later – how did that process go? Well, Chayse was the DP who came and shot Ana’s screen test for free. [Laughs.] People had recommended him, and he did it really well, so I felt since he’d done it for free, I should get him to do the movie! [Laughs again.] But honestly, I feel that since we switched over to digital, this new generation of cinematographers who have grown up with digital use it better than the old masters. I feel like the old masters are trying to make it look like film, and that’s not what I wanted. The most interesting things happen when you find the usable mistakes and the peculiarities in the technology that you can use aesthetically. I feel that if you’ve grown up with film, it’s a whole different set of peculiarities you’re using. Whereas if you’ve grown up with digital, if that’s all you’ve ever worked with, then that voyage of discovery is tied to the actual medium, if that makes any sense. Cinema has changed enormously; it’s not about lighting anymore. It’s about available light and lens choices. The young guys are always looking for unusual glass, and the film DP’s, I’ve found, often have a particular set of lenses they love that work. Having said that, Chayse also shoots a lot of film. I think this is the first feature he shot on digital, and he was actually disturbed by that. [Laughs.]

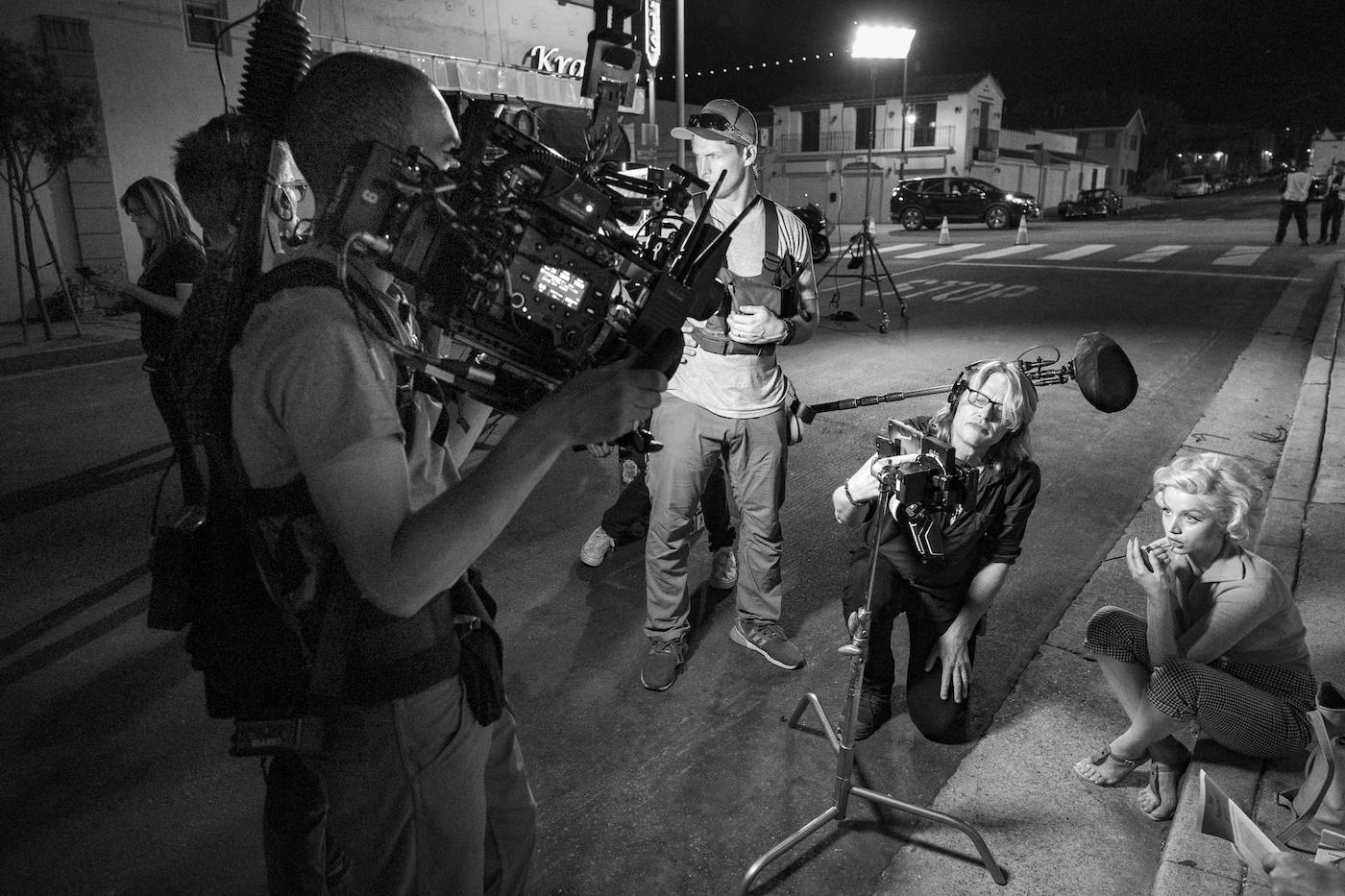

Chayse talked about a spontaneous vibe on set where his choices were led from intuition rather than a shot list. Was that your experience? Well, I did have a shot list. [Laughs.] But for the most part, the film was worked out via a plan that I was always ready to abandon. Often it was about how we reacted to the physical space of certain locations or how the light behaved in those locations. Another thing I like about Chayse is that he has a still photographer’s attitude towards lighting; he works around the light rather than getting the light to work for him. It’s thrilling and a lot more fun. And Chayse brings a soulfulness to his imagery; he’s not just attracted to what people will think are pretty pictures. He’s attracted to something that’s more…raw. We wanted to get beyond the beauty part with Marilyn. Visual beauty is comfortable, reassuring and safe, and we were looking for something different.

So how would you summarize your on-set collaboration? There are not many DP’s who just do it, you know? Like Chayse is game even when you’re shooting your biggest extra days and there’s no lighting, just the lamp on the front of the camera because we’re trying to imitate flash photography and it’s your most expensive day. The director and DP have to have a very strong relationship shooting a movie. And then there’s the relationship between the first AC and the actor that also needs to be strong. [A-Camera 1st AC] Jimmy Ward was quick and instinctive and ready to just go get a piece of Mylar or whatever. We tested a lot, but things on the day were improvised and built around the location.

The camera’s positioning and movement made viewing this film a very intimate experience. We’re literally inside of Marilyn, following her conceptions, miscarriages, and abortions. Tell me about that choice. We wanted to give you the experience of being her, as the primary relationship in the film is between the audience and Marilyn; it’s not between Marilyn and the other characters. And that’s shown through an incredibly narrow [narrative] lens. She’s misunderstanding the world, and none of the other characters in the story understand what’s going on with her, but we, the audience, understand everything. So, it does create an unusual kind of intimacy where you understand what’s going on but you wonder why no one else can see it. That’s the whole drive of the film – to make the viewer want to shake her, and you just have to sit there helplessly as she destroys herself.

And we are very close to her face – a lot. Ana’s face resolved itself most like Marilyn’s on a 50-millimeter lens. My favorite lens length is 35 millimeters, but with Ana’s face on a 35 millimeter, she would become a bit more angular. So, much of the movie is shot on a 50-millimeter for that reason. We did have rules about filming her face, like you couldn’t be below her chin, you had to be at eye level because that was when she looked most like Marilyn. There’s a tendency nowadays, and I see it in everything, to shoot low. Look at most TV shows, and they’re shooting from the ground. I don’t know what that’s about, but I guess people like seeing the roof or they think those are interesting compositions. [Laughs.]

You created whole scenes around the many famous real-life photographs of Marilyn; was that an idea you’d always had as to how to visually approach Blonde? I had a bunch of different ideas about how to approach it over the years. My first thought was to utilize that weird fairytale architecture we have in Hollywood. Then I saw that German artist, Thomas Demand, who recreates famous news photographs by building them in cardboard. It’s disturbing to see because you know the image, but it’s simpler or there’s something about it that’s not right. It’s distressing in some way. And I thought, “Well, I could do a similar thing with photos from her life.” I wasn’t ever looking for good aesthetic environments; I was looking for environments that she actually lived in.

And you used a lot of real locations from Monroe’s life. The first thing I did with the location scout was to get a list of the 28 places that she’d lived in Los Angeles. First, we searched Google Images to see if they still existed, and a bunch of them did. And then we drove around to see which ones we could get into, or couldn’t, or which ones had changed, and which ones hadn’t. I based a lot of the film around what I found out from that research. When you’re putting the actress in exactly the same clothes, in exactly the same position, in exactly the same room, at exactly the same time of day, you can’t help but create a séance. And Ana would always somehow hit it. I remember shooting that scene where Marilyn’s in the window with DiMaggio [Bobby Cannavale], and Ana had been on the movie for a couple of weeks. Bobby’s sitting there, holding this pose, and we’re just telling him, “Okay, move your arm here. Okay, Bobby, move your leg there.” He’s like, “Are you kidding me? We have to stay still when we do this scene? I have to do the scene in this position? Are you crazy?” And Ana is just saying, “Don’t worry. It’ll be okay,” calming him down, telling him it’s going to work. And then Bobby gets it and is like, “Let’s do this.”

This is not the first book you’ve adapted into a film. Has that been a deliberate choice? And what is it that attracts you to that process? I like other people’s visions of things. When you read a book, you have an emotional experience and you translate that into your own emotional experience, your own surprises in reading it. I’m a creative person, but I don’t like to make things up. I like true stories.

You described Blonde as a “lucky” film. Can you explain? Well, we managed to get Fox and MGM to allow us to put Ana de Armas in Marilyn Monroe movies with George Sanders and Tony Curtis – that seemed impossible. Like, there was no way that anyone was ever going to allow us to do that, but we were lucky in that Rupert Murdoch sold Fox, and a more reasonable guy started running the thing. And then, in pre-production, the guy who was running MGM at the time was like, “Over my dead body; this will never happen.” But he lost his job, and Michael De Luca took over and was up for it. Getting into her house [is another example]. It was so hard to do that, but somehow it all worked out. It’s unusual on a movie that seemingly impossible things go that well.

Why do you think it took 12 years to get this movie out into the world? I needed to raise a certain amount of money to make the film, and my previous films haven’t been financially successful. It’s a difficult business, Hollywood. I think the psychology is that when something’s been around for a certain period of time, people wonder why nobody else has done it. They think, “Well, maybe we shouldn’t do it.” But that’s the wrong way to think. If there’s a good director who wants to do something and consistently wants to do it for a long period of time, you probably should do it! Hollywood is motivated by fear of loss of whatever’s currently hot, and I don’t understand that. I mean, speaking honestly, this film was brought to life at a great personal cost to me. I don’t want to keep doing it if it’s always going to be like that.