The Guild team behind the indie comedy, Dog Days, sniffed out valuable lessons from their unpredictable canine stars.

by Pauline Rogers / Photos by Jacob Yakob

Any pet owner knows dogs can frustrate the heck out of you: chewing on your favorite shoes, peeing on the most expensive item of clothing you own, and sometimes cleaning off the dinner table before you’ve even had a chance to sit down and eat. On the other hand, our four-legged companions show us the unconditional love we all crave; they make our darkest days bright, and can sense the best in friends and strangers, making them ideal matchmakers.

That last attribute is what childhood friends, director Ken Marino and cinematographer Frank Barrera, aim to celebrate with the release from LD Entertainment of the indie feature, Dog Days. The film is mainly a traditional multi-narrative romantic comedy, with the twist being that all the prime story arcs, among them characters played by Nina Dobrev, Eva Longoria and Adam Pally, are impacted, in some way, by the dogs in their lives.

Determined to pop that old industry balloon, “never work with kids or dogs,” Marino and Barrera have created a film with all types of four-legged friends, and the quirks that make them so frustrating and wonderful at the same time. “Initially we studied lots of other romantic comedies but also lots of dog movies,” Barrera says. “We looked at the visual language in both genres, with two of our touchstones being Love Actually and A Dog’s Purpose. Both films are great examples of how color can be used to support the style of storytelling that interested us.”

One of their main concerns was highlighting the unique character of each lead dog – from Chihuahua to Golden Retriever – who all possessed unique characteristics and intelligence. Marino says he wanted, “people to want to pet this movie!” Adds Barrera in support of his director’s vision: “We knew we were getting a theatrical release and loved the idea of having these beautiful animals projected onto a large screen.”

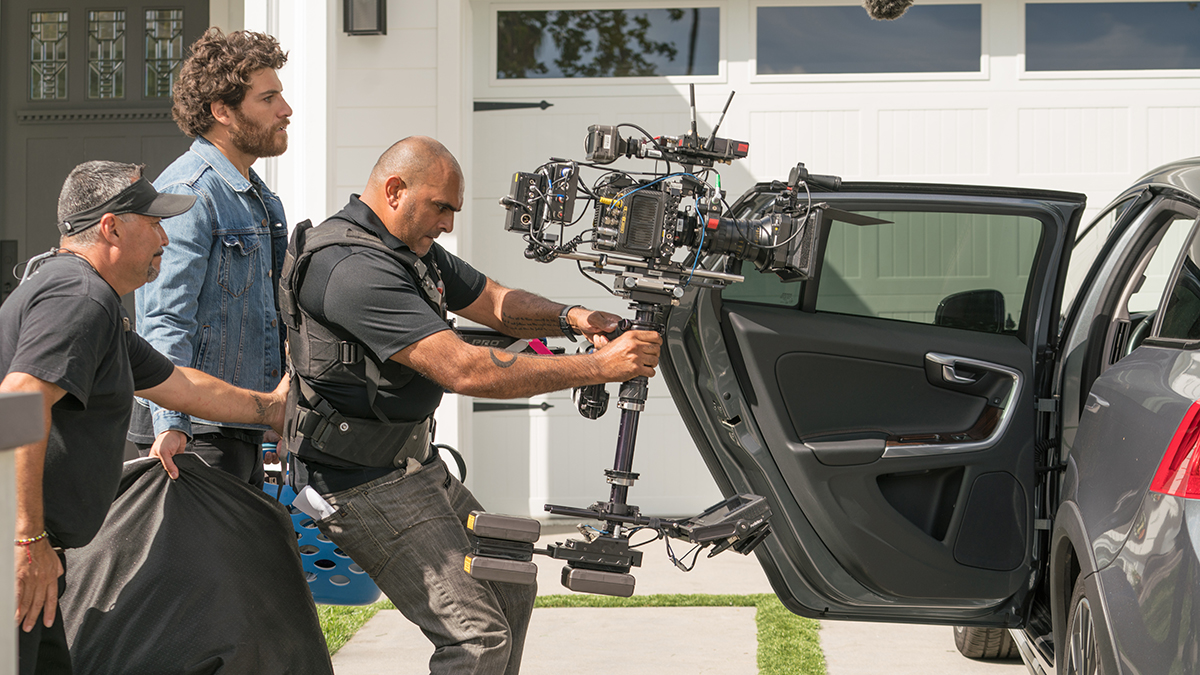

To that end, Barrera, along with First AC’s Cheli Clayton and Harrison Reynolds, set up tests with the ALEXA MINI. “We set out to find which of our full set of Cooke S4 Primes and Angenieux Optimo zooms would have the best look when we filled the frame with the dog’s face,” the DP explains. “We wound up with a range of 35mm to 50mm for close-ups, depending on the size of the dog. In the reality of production, we sometimes had to swap the primes for the zooms, just because the dogs wouldn’t always sit where we wanted. Live zooms were not uncommon as we chased the animals.” When A-camera/Steadicam operator Twojay Dhillon joined the test, the discussion turned to support, and the addition of the Super Post.

The other consideration was frame rate. From experience, Barrera knew that shooting close-ups of dogs at 30 frames per second was optimal. When transferred at 24 frames per second the slight slow-motion effect “magically brings out an intelligence in the dog’s eyes,” he explains. “Also, the animals are often in constant motion, so the 30 frames per second helps slow them down just enough for the viewer to gain a little more access into the dog’s personality.”

While Dog Days is no action movie or high drama, its comedic challenges were still mighty. Or as Barrera observes: “Even the best-laid plans can go out the window.” He cites a series of scenes in Dax’s (Adam Pally) apartment, which was shot in a loft on the 7th floor of a building in one of L.A.’s historic neighborhoods, which holds many restrictions for film shoots.

“We thought we had access to street parking for an 80-foot lift that would carry an ARRI M90 HMI and simulate direct sunlight streaming into the apartment,” Barrera recounts. “But on the day, we discovered that we were not going to be able to put a lift outside – all of our lighting would have to come from inside. The scenes all take place just as the sun is rising, so the obvious approach was to have the sun come in through the windows.”

The on-the-spot solution, Barrera shares, was to “use a single Joker 800 inside the room, with a complex array of flags and shapes cut from foam core to imply sunlight. We also used some small pieces of shiny-sided beadboard to steal some of the Joker’s beam and send splashes of light around the room. I often look at recreating the randomness of direct sunlight that bounces around inside of interior locations.”

Location-driven, indie shoots like Dog Days typically experience such challenges. Key Grip Joseph Dianda recalls a scene with an old man who lived in a craftsman style house with a dark interior. “Because we worked in many different directions in one shot, and used two and three cameras,” Dianda says, “Frank decided to line the exterior of the house with 18Ks and 12 x 12 ½ grid, projecting them in through the windows. It helped us make the schedule.”

“We made this a very large soft source from outside, motivated by the sun,” Barrera adds. “I love allowing the light to bounce around in surprising ways. This gave a naturalism that fit this beautiful house.”

As for the most obvious challenge – the dogs – D.I.T. Dane Brehm managed exposure and onset color so that Barrera could focus on lighting human and animal actors, (in conjunction with Digital Utility Richie Fine wrangling their Wireless Video Tree). Brehm says it was about allowing the actors to do scenes while not tiring or over-stimulating the many different dogs.

“One of the most comical scenes I can recall was when Dax arrives at his sister’s house with his new furry pal, and a tower of party items in his hands,” Brehm recounts. “Adam’s physical comedy with one of our dogs, Charlie, as his character attempted to park his van, pull out the party items, and deliver them to his cranky sister made for a great moment that was never the same twice.”

“Part of the fun on this shot was what you weren’t seeing,” Dhillon adds. “It was a big tracking shot across the front of the van. We brought the van to the house and landed it. There were the usual height adjustments and marks; anything we had to hide was across the street, so it was not a huge technical challenge. The hardest part was, literally, to stop the camera from our shaking and laughing. Our dog had a love affair with Adam Pally’s leg! At one point, without breaking character, Adam turned to the dog and said something like: ‘don’t you think you should buy me dinner first?’ We totally broke up, and still got the shot, which is in the trailer.”

Dhillon did have more serious issues, mostly connected to the vast range in size of each dog and their movements within the story. The operator tops out at six-feet, so running backward with a Steadicam, and trying to shoot a newly trained Chihuahua, barely nine inches off the ground through a street in Silverlake, was a stretch.

“Since the standard Steadicam could get the camera barely below my knee, we brought in an ever-bigger piece of equipment – the six-foot Super Post to get eye level with our star,” Dhillon explains. “Cheli was pulling focus, and neither of us even wanted to look at the crowd or imagine what they were seeing. We just wanted to make the comedy work.”

One practical challenge the Guild camera team faced on Dog Days concerned a major physical change in one of the doggie stars. Grace (Eva Longoria) and her husband have suffered the shock of temporarily losing their daughter. When they find her, along with a lost dog she has found, they wind up bringing the dog, Mable, home with them. Mable is overweight, and over time they bring her back to a healthy weight. Any typical production would use makeup prosthetics or padding, but on a dog?

Dhillon says they had to shoot a series of similar dogs and make sure their appearances (through camera movement) appear consistent. “We had to change the camera angles,” he adds. “Dungie the pug wasn’t a highly trained dog actor. The trainers worked him so much that he lost a lot of weight. At one point I had to shove the camera really close to the dog so that we could get fat rolls. In the next film, we need to talk about getting doggie fat suits!”

Dianda recalls that, “at one point, Ken [Marino] wanted a dog to walk as if he was stoned! We were going to build a separate set and do it as an insert, but we didn’t have the money nor could the dog function with a moving set. The animal trainer tried to train the dog to walk like it was stumbling. But that didn’t work on film.”

“Charlie is supposed to have accidentally eaten some pot brownies,” Barrera adds by way of a narrative motivation. “In the end, our wonderful trainer, Mark Harden, got Charlie to lie on his back with outstretched paws. It’s hard to describe the position he was in. But we shot at 40 frames-per-second and it came out looking just strange enough for the viewer to realize that the dog was not well. We really sold the physical comedy by shooting a locked-off wide shot utilizing a split screen with Charlie on one side at the 40 frames-per-second and Dax on the other at 24 frames-per-second. It’s strange and funny.”

Operator Karina Silva, who also served as 2ndUnit DP and was in charge of filming the letting-the-dogs-run-around-footage, says canine mayhem was a typical occurrence. “I think I speak for the rest of the crew,” Silva intones, “when I say the biggest challenge on this film was trying not to laugh so hard that the camera would shake.

“We had a simple shot one day where we had the 12:1 plus a doubler on and Harrison and I had to shoot an extreme close-up of a pug running directly at us,” Silva recalls. “I had to zoom out to keep the ECU during the whole take. No rehearsal. Just hoping for the best. And no second try, because we wouldn’t get the same [movement from the dog]!”

Making comedy look cinematic is hard enough with a human-only cast. Add in a pack of unpredictable dog stars and the complications become exponential. The trick, according to Barrera, is having a talented crew with patience and a sense of humor. “One of the biggest lessons we learned was when working with the dogs, where they were being featured, we couldn’t rely on a complex Steadicam move,” the DP, whose TV credits includes The Mindy Project and Funny or Die, shares. “This might seem obvious, but we were optimistic that we could incorporate interesting Steadicam moves along with some trained dog action. The reality is that no matter how well trained the animal is, you’re asking for trouble if you build in a complex move that relies on the animal hitting specific marks take after take. And, if you decide that you need to do it anyway, you need to build in enough time in the schedule to allow for blown takes.”

Dhillon, whose recent operating credits include New Girl and Cooper Barrett’s Guide to Surviving Life, adds that, “as much as we used the Steadicam for the complicated moves, we found that if we went with a more freeform format, making adjustments more quickly, and knowing the dog didn’t have to hit a mark, we got more natural doggie-ness. They tend to look at their marks when they hit them, and then look up for encouragement. It takes the shot out of the moment.”

Brehm says that each dog role may actually be played by several dogs with multiple specialties, “and the lesson you learn quickly is how important it is to be close with each of the trainers, as they spend thousands of hours with these animal actors. Then, when the next shot in a series is up after hours on the set, the camera team has to learn to get the most out of each dog before they get bored or tired. For me, as the D.I.T., and for the camera crew, it’s all about adapting on the fly without sacrificing focus, exposure or concentration.”

Silva adds that “you quickly understand the dogs don’t really care about the shot or the movie. They are so present and honest and will do what they are either trained to do – or what they feel like doing, in that moment. Sometimes it works – sometimes it doesn’t, and we, as camera people, have to know that. At one point, we had a tender love scene, with a dog close-up. We were hoping for cute. Instead, the dog kept nodding off and falling asleep during the monologue! Not scripted. But hilarious. When working with animals – you need to go with the moments, and this was definitely one of them.”

Or as Barrera concludes with a smile: “When Ken and I were growing up, we used to sit around and talk about someday making a movie together. If you had told us our first feature would be a ‘dog film,’ I don’t think we would have believed you. But I’m glad we did it.”