Union members pay tribute to award-winning Director of Photography Allen Daviau, ASC.

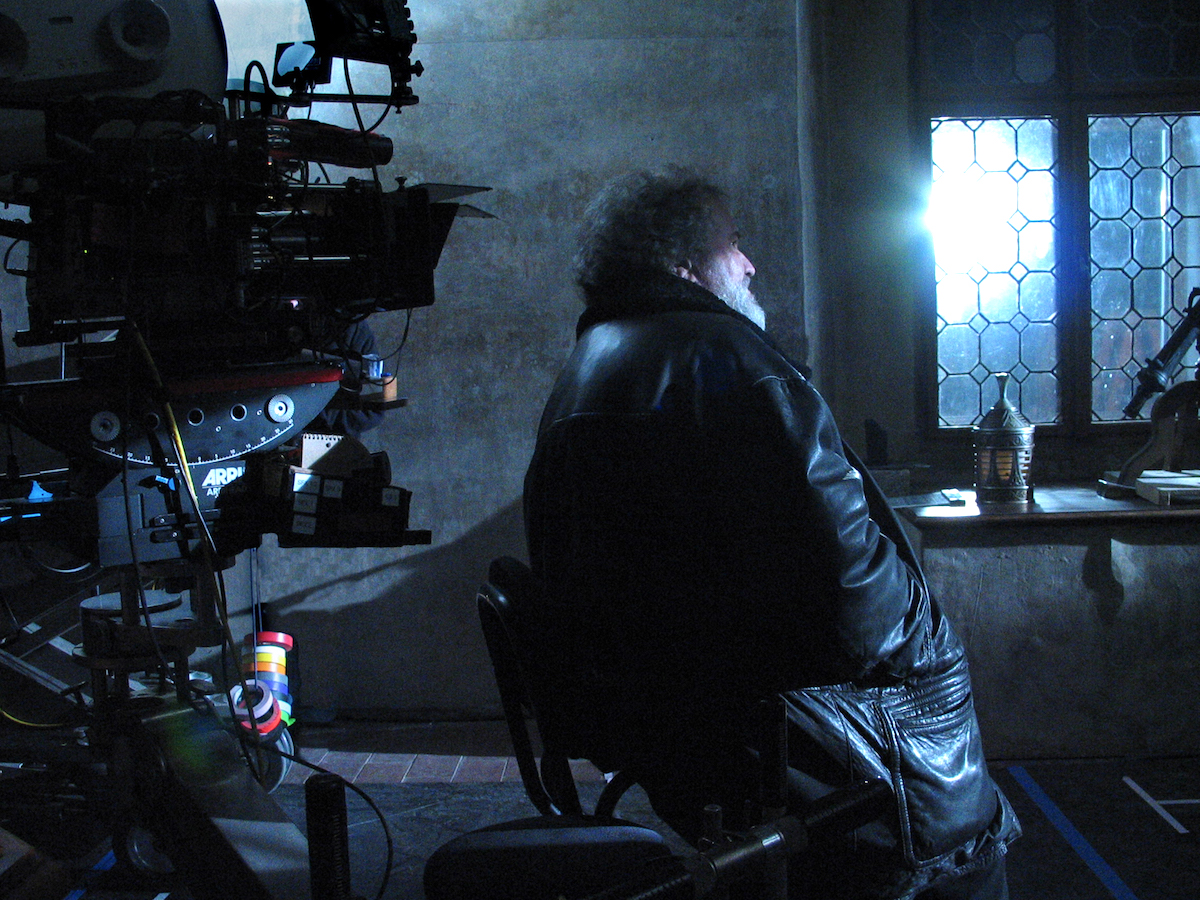

by Pauline Rogers / Featured Image Courtesy of Bruce McBroom

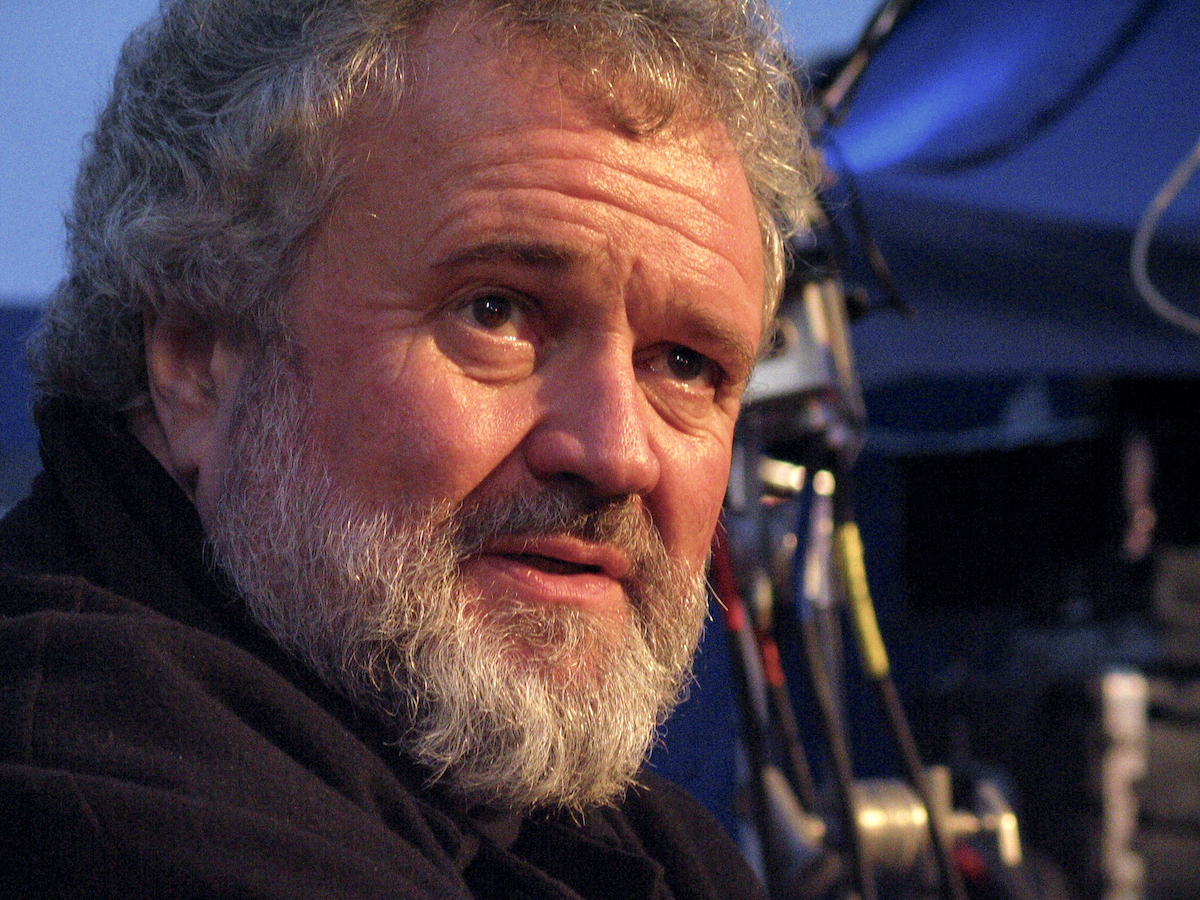

The internet blew up on April 15th, 2020 when it was announced that cinematic icon Allen Daviau, ASC, passed away due to complications from COVID-19. Tributes and memories poured in. Journalists opined how Daviau was a five-time Academy Award nominee for classics like E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (1982), The Color Purple (1985), Empire of the Sun (1987), Avalon (1990), and Bugsy (1991) – but never actually took home an Oscar. Or how he was awarded a BAFTA for Empire of the Sun (1997), and no less than three ASC Awards, including a Lifetime Achievement Award in 2007, as well as a second Lifetime Achievement Award from the Art Directors Guild ten years prior, not to mention even more nominations across the various arts.

There was recognition of his early years in music – pre-MTV – and the hundreds of commercials he shot. Fans who held a passion for the extraordinary eye of this bigger-than-life artist chimed in with their favorite memories of sequences that will stay embedded in the industry (and the general public’s) collective minds-eye.

And there was more. The ASC published an extensive conversation with Daviau, covering his memories of the work that was his passion for so many years. There was even a reprint of a conversation about his break-out film E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial. The film’s star, Dee Wallace Stone and Avalon star Elizabeth Perkins both tweeted out thoughts of the profound loss they felt, even though neither worked with Daviau in many years. And as befitting an artist of his stature, filmmaker Stephen Spielberg voiced what a tremendous loss Hollywood had endured via a letter he’d written that was read to Daviau during his final moments at the Motion Picture & Television Country House and Hospital.

All of the above-mentioned tributes detail the broad strokes of Daviau’s artistry, but they don’t necessarily highlight his lifelong dedication to his IATSE brothers and sisters, and how much Allen Daviau did over his long and stellar career to support them.

That’s why for this month’s Web Exclusive, we’ve assembled some memories from the union craftspeople whose lives were touched by this extraordinary human being.

The title of this article – Riding In The Car With Allen – is ironic, as most everyone who knew or worked with Daviau knew he didn’t drive. But when with this big-hearted man asked others to drive him, it was rarely about getting from point A to B, anyways. It was more a way of sharing his passion for filmmaking with his peers and colleagues.

Hopefully, Allen Daviau, ASC, is watching over his Local 600 brothers and sisters as we speak, and enjoying this final ride we’ve assembled, comprised as it is of memory snapshots, gourmet dinners and a community of like-minded artists who all loved taking “a ride with Allen.”

John W. Lindley, ASC

“One hot, sunny L.A. afternoon, I slalomed through the front yard of an ASC Open House and, as I crossed the threshold of the front door, I looked to my right and saw a group of young men and women seated on the floor, facing the sunlight streaming through the windows. Their rapt attention was focused on someone I couldn’t see, but as I kept walking, I saw who had hypnotized this cult-like group. It was Allen, who was sitting on a low chair and talking about his favorite subject – cinematography.

“Part Buddha, part Santa Claus, all Daviau. He was sharing his knowledge, enthusiasm, and experience with a bunch of young people who were eager to hear everything he had to say. If English wasn’t my mother tongue, I still would have understood simply by observing. What he also imparted that day was the value he placed on sharing his vast knowledge, because when blended with his artistic talent, Allen had reached a peak that put him at the top of his craft as an artist and as a human being.

His loss is heartbreaking, but his legacy will only grow.”

Steven Poster, ASC

“Shortly after I first relocated from Chicago to Hollywood in 1975, I got a call from Allen Daviau, inviting me to lunch. Allen said he had heard that I made the big migration and was trying to get a foothold in the market. I was thrilled. We met at the old Formosa Café, where we settled into one of Allen’s famous lunches! He had already arranged to pay, so I could do nothing about that. But he did say to me: ‘You have a car? I need a ride home, and I have to make a couple of stops along the way.’ I, of course, jumped at the opportunity. The stops he had to make were introducing me to several of his clients. And that was how some of my very first jobs in Hollywood came about.”

Dejan Georgevich, ASC

“One night in 2006, I offered to drive Allen home following hours of negotiations. As we drove along Ventura Boulevard, in the Valley, Allen would point out passing storefronts, namely photo stores where he had worked during his first years in Los Angeles. It was a memorable evening listening to him share his excitement and passion for cinematography, culminating in an exquisite dinner at his favorite restaurant in Burbank. I’ll always remember Allen as a warm, amiable, brilliant, legendary cinematographer, who inspired so many of us.”

Shelly Johnson, ASC

Allen Daviau, ASC, was a primary mentor and teacher to me, and he seemed to have a hand in all my career milestones; he opened many doors – not only professionally, but also artistically. I met Allen when I was 18 and I was excited by his energy and love for the art of cinematography. He taught me to think about new techniques. New ways to tell a story using a balance of acquired knowledge of the science of film with a pure, artistic truth. He was generous with his wisdom and showed me that an interchange of ideas was key in becoming a respected cinematographer. One story that stands out was when I was offered the film, Jurassic Park III. Allen called me to his home to screen his film, Congo, and discuss the nuances of shooting a stage-bound jungle set. He wanted to show me what worked and what he felt did not work (there wasn’t much that did not work, by the way). This interaction appeared to benefit me exclusively, and him not at all. Yet we talked for hours, and what I learned went much deeper than a lighting discussion. He talked about his “reasons-why” Why he made the choices he made to best satisfy his artistic intent. I don’t know why he was so generous with me for so many decades. People sometimes ask me why I help young cinematographers… and this is why. It’s possible Allen was paying forward some unpayable and valued debt on behalf of a past teacher. For those who did not have a chance to meet him, you can get to know him through his movies, my favorite being Empire of The Sun. Allen’s films are heartfelt and made lovingly with wisdom and a gifted mastery of the art. He said his primary goal was to create images that made the pauses speak as eloquently as the words, and to create screen moments that existed purely because of how they were photographed. I think his impact on our lives is similar and I’m thankful that I can go forward with his images, as well as his words.

From his E.T. family…

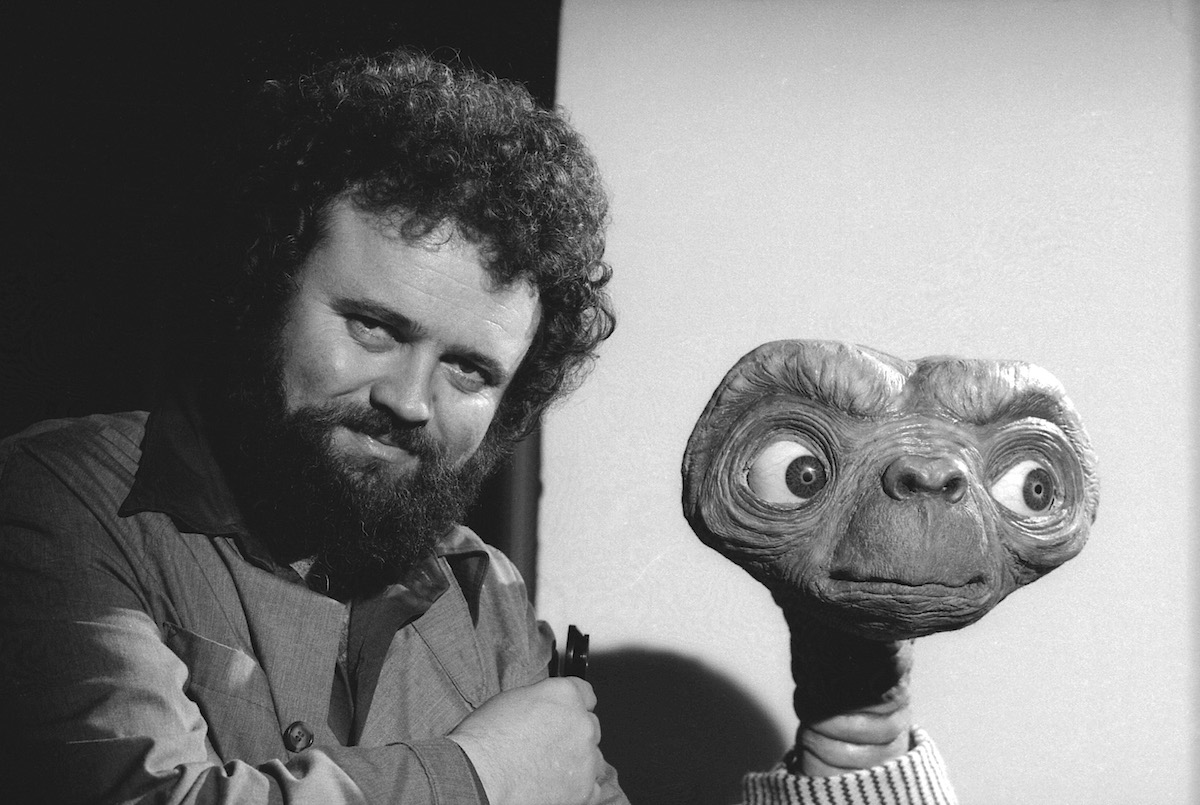

Bruce McBroom, Unit Still Photographer

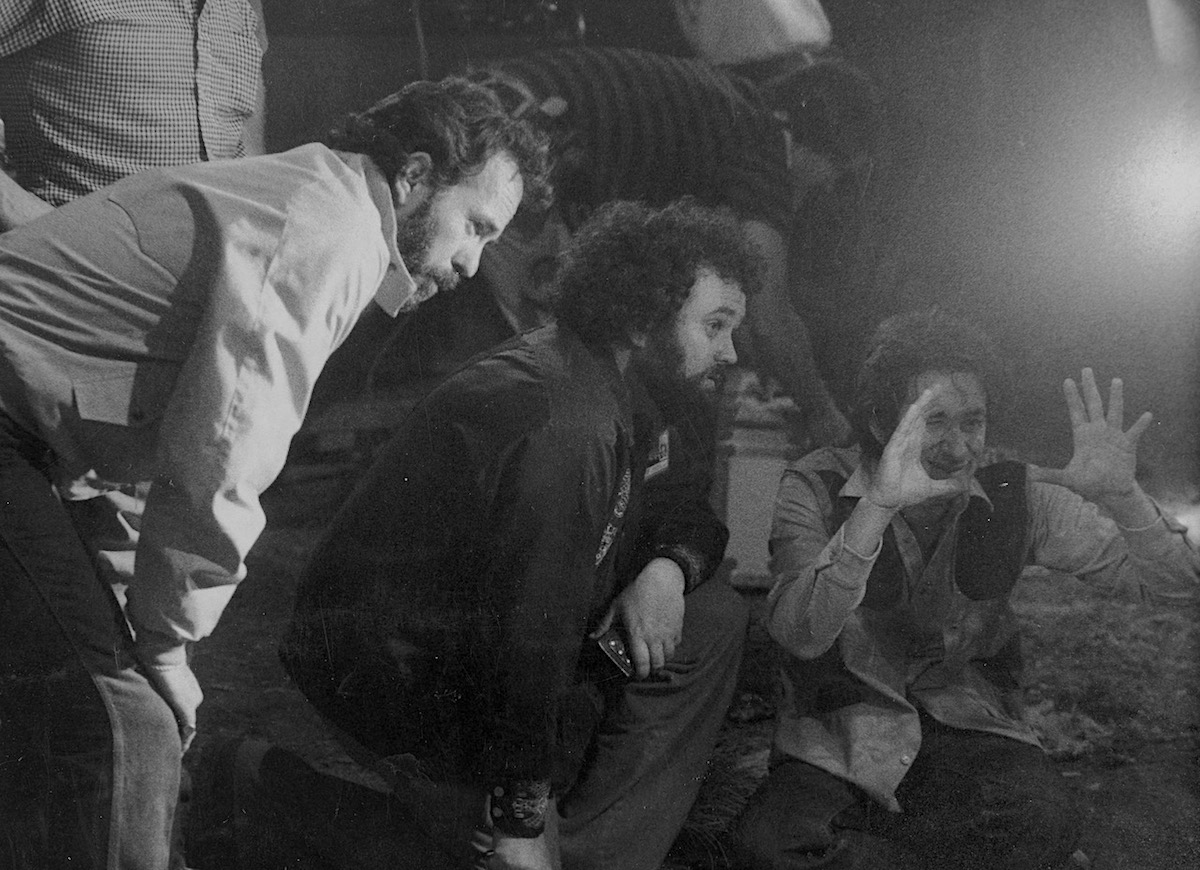

“In 1982, I was hired on a small film project called A Boy’s Life, with Steven Spielberg directing. None of us were given scripts to read, just the pages for that day’s shoot. We all signed security agreements and had I.D. badges. If you showed up without your badge, you were not allowed in by the security guards.

“This is when I first met Allen Daviau. He was very kind, quiet, and generous. It was obvious that he and Spielberg had a plan, but the majority of the crew was left in the dark, figuratively and literally. There were very low light levels, lots of smoke, and technically challenging sets. Watching how Allen and Steven collaborated, with all their give and take, is still memorable to me. Allen knew just how to realize Steven’s vision, which was sometimes very risky in terms of traditional cinematography. Each of them brought out the best in the other. Given this current crisis, it now feels so ironic that I can still remember walking onto the set of E.T. each morning, at Laird Studios, and being given an N95 mask to navigate the vast, smoke-filled stage.”

Jim Plannette, Gaffer

“When I was working on Cannery Row, Allen Daviau was looking for a gaffer for an upcoming project that he said would ‘try to do a lot with little.’ We met and immediately clicked. Without really saying it, we played ‘good cop, bad cop’ on that ‘little film.’ If there was something Steven [Spielberg] would be happy with, Allen told him. If it wasn’t good news, I told Steven! The hours weren’t too long because of the kids. We saw dailies every night at Steven’s house because his projection was better than at the studio. A Boy’s Life turned into E.T., and that turned into a lifelong friendship. I saw Allen a few months ago at the Motion Picture Home. Henry Thomas, the young man who played Elliott in E.T., had sent me a commercial based on E.T. that I wanted to show Allen. He loved it and had a big smile on his face as he watched it.”

John J. Connor, Camera Operator (retired as Director of Photography)

From commercials to features like E.T. and Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, Connor says he learned much from this “informative, always low-key” and in control person. “Allen was always anxious to share his knowledge,” Connor recalls. “A treasure trove of information. He had a keen sense of all the down-side risks of shots for an assistant when it was difficult, and kept that in mind when you were designing shots. He was a great collaborator, open to all those around him, and would listen to any thoughts about shots. He was a perfect mentor to all. You will be missed by all those who had the privilege of knowing and working with you, my friend.”

From his Avalon family

Barry Wetcher, Unit Still Photographer

“A few weeks before we began principal photography on Avalon, Allen called. For me, it was a first to have a cinematographer calling me before we started just to introduce himself. During production, on weekends, Allen would borrow my loupe and lightbox, and he would look at a select group of slides. Again, who does that?

“Allen was truly a master, painting with light in such an elegant way. Always tweaking. Sometimes I’d look over, and there would be Allen, sticking his finger in front of a light just to cast the slightest shadow somewhere in the frame.

“He loved to eat great food, and I will always cherish a Thanksgiving dinner he and I shared in a Baltimore hotel.

“Allen was afraid of heights. I’ll always remember two grips on either side of him walking him up a very high steep set of stairs. On a few occasions, he gave me his meter and asked me to read the light. For me, that was an honor. I lost a friend. And the world lost an amazingly talented individual.”

Peter Norman, Camera Operator (retired as Director of Photography)

“Allen was a gentle man, as I never heard a single complaint during the screening of the Avalon rushes. My fondest memory was on a couple of scenes where he had a large black paper hung across the set, just ahead of the cameras. After each take, he would step in and tear off just a little piece of the paper. Here an inverted V; there a rip; here a chunk taken out – all to allow just the right amount of light through to the scene. He did this after each take, and I could see director Barry Levinson shaking his head and smiling. That was typical of Allen. When we were shooting, his whole being was concentrated on the scene. I feel that, if allowed, he would still be tearing off a little piece of that black paper until he hears ‘Let’s Roll!’”

Bobby Mancuso, 2nd AC (now A-Camera 1st AC)

“I was a second AC with Reggie Newkirk on Avalon. Allen would explain to me why he was lighting a certain way. One little thing he told me was one of the DP’s best friends is the on-set Scenic Artist. Of course, this was when we were still shooting film and before most of that stuff could be done in post. After we finished, he asked me if I would like to come to L.A. to do an Albert Brooks movie called Defending Your Life. I wasn’t a member of Local 659. He said as long as I had the 100 days, I was eligible. I needed letters from DP’s. Allen called them personally. If it hadn’t been for him, I probably never would have gotten into 659, and had the career I’ve had. He was a special man to me. And an incredible cameraman.”

Jimmy E. Jensen, A-Camera 1st AC

“Allen was quiet and shy. He was terrified of anyone knowing his birthday because he was afraid of everyone singing to him! So, we found out the date and told operator Paul Babin. He organized our camera department – a cake and a happy birthday song on set. On cue, the entire crew sang while Paul, Second AC Nick Shuster, and I all hid behind the green screen and laughed. Allen was so embarrassed and red. But it was worth the celebration that he so much deserved.”

Craig Fikse, Steadicam Operator (now a Director of Photography)

“It was near the end of the Van Helsing schedule in the middle of shooting a horse-drawn carriage scene with Hugh Jackman and Kate Beckinsale. Out of the blue, Allen turned to me and said, ‘Craig, do you have a light meter?’ I was surprised because I wasn’t sure where he was going with the question. It had been years since I used my light meter. I’d have to dust it off, and I was sure the batteries were long since dead. Nevertheless, I replied, ‘Yes.’ Allen said, ‘Great, I need you to shoot a quick splinter-unit shot. It’s a close up of Frankenstein, in the rain, with lightning, hanging 20 feet above a 40-foot by 40-foot blue screen. You think you can do it?’

“I froze. Was he actually asking me to shoot film for him on this massive movie? Try out my cinematographer chops? We talked briefly about his vision, and he sent me, the gaffer and key grip on our way. Within a few hours, I found myself and my First AC, Al Cohen, 30 feet up in a Condor, looking straight down the wall. Actor Shuler Hensley, who had spent hours in makeup, was being raised up. Director Stephen Sommers came over to direct the scene. I held out my light meter (with fresh batteries). Roll Camera.

“When the scene was finished, Allen asked, ‘How did it go?’ I hesitated and replied, ‘Ok.’ Allen nodded and smiled. ‘Great. Tomorrow morning, at 5:30 a.m., I want you to meet me at Technicolor. We are going to review your dailies…together.’

“I was so nervous when I sat down next to him the next day; I was hoping we weren’t going to be staring at a black screen with nothing exposed. He did think I underexposed the key light one-third of a stop. But he also said the eye light, and the lighting strikes were on the money. ‘Sometimes you have to make choices,’ he told me. ‘I think you made the right ones.’ When someone places a task before me, or a shot that seems out of my comfort zone, I think back on Allen and his encouragement. I remember that accepting challenges is what this business is all about.”

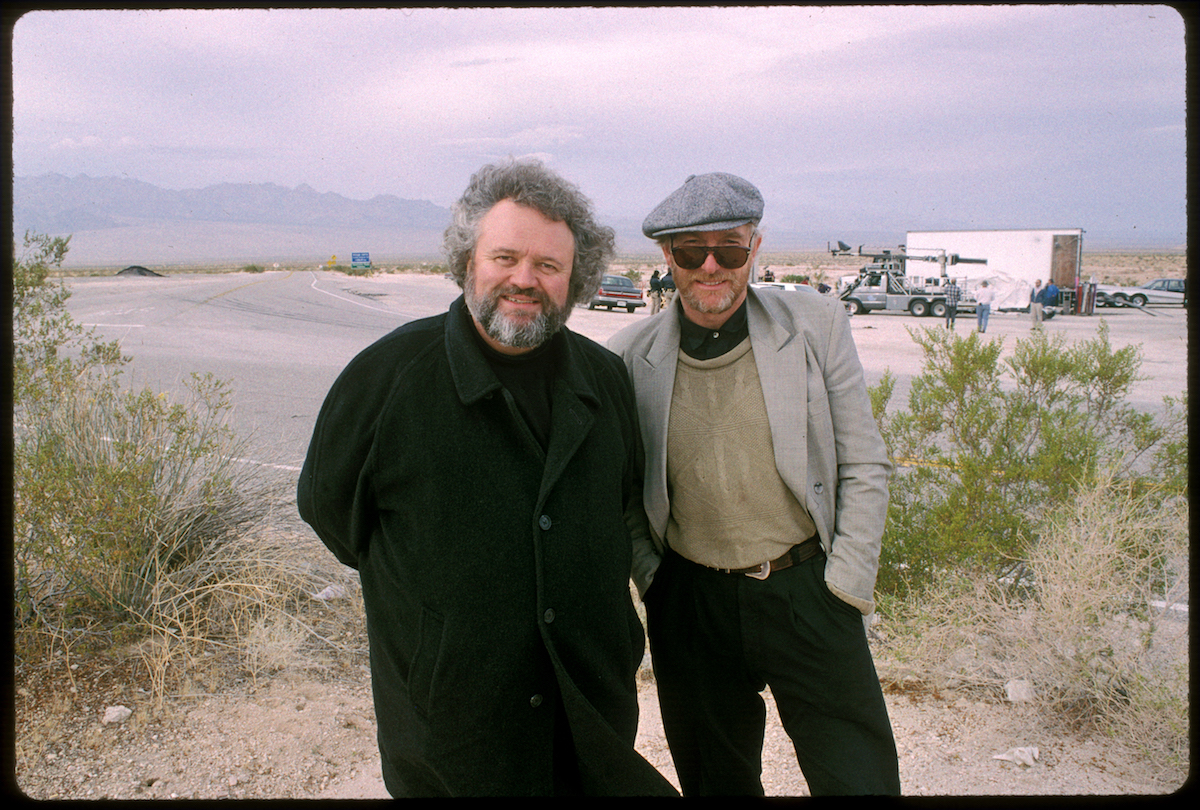

Director of Photography Shana Hagan, a member of the Academy of the Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, who has shot Oscar-winning documentaries like Breathing Lessons, as well as more than a dozen Sundance Film Festival debuts, sums up what it was like to step into the world of Allen Daviau. Besides sharing his art, special car rides with intimate insights into his past, and of course, the best gourmet meals, Daviau taught everyone he touched about life, as Hagan reflects:

“Allen taught us how important it is to keep your creativity alive. Especially when work is slow. To do something every day to stay creative. Watch a movie, read a book, go to a museum, work in your garden, walk around your neighborhood, take some photographs.

“And when we’re doing that,” Hagan concludes, “observe and remember the moments that inspire. Maybe it’s how the late afternoon light falls on a curtain blowing in the wind, and how you emotionally respond to that light. Or maybe it’s a painting or a sculpture that moves you in some way. Or the color of a flower blooming in your garden. It’s about staying engaged creatively through observing and learning from the world around us. This was a gift that Allen gave to all of us.”