A 6K Data-intensive workflow enables Jeff Cronenweth, ASC, to chase down a “gone girl” in his newest collaboration with David Fincher.

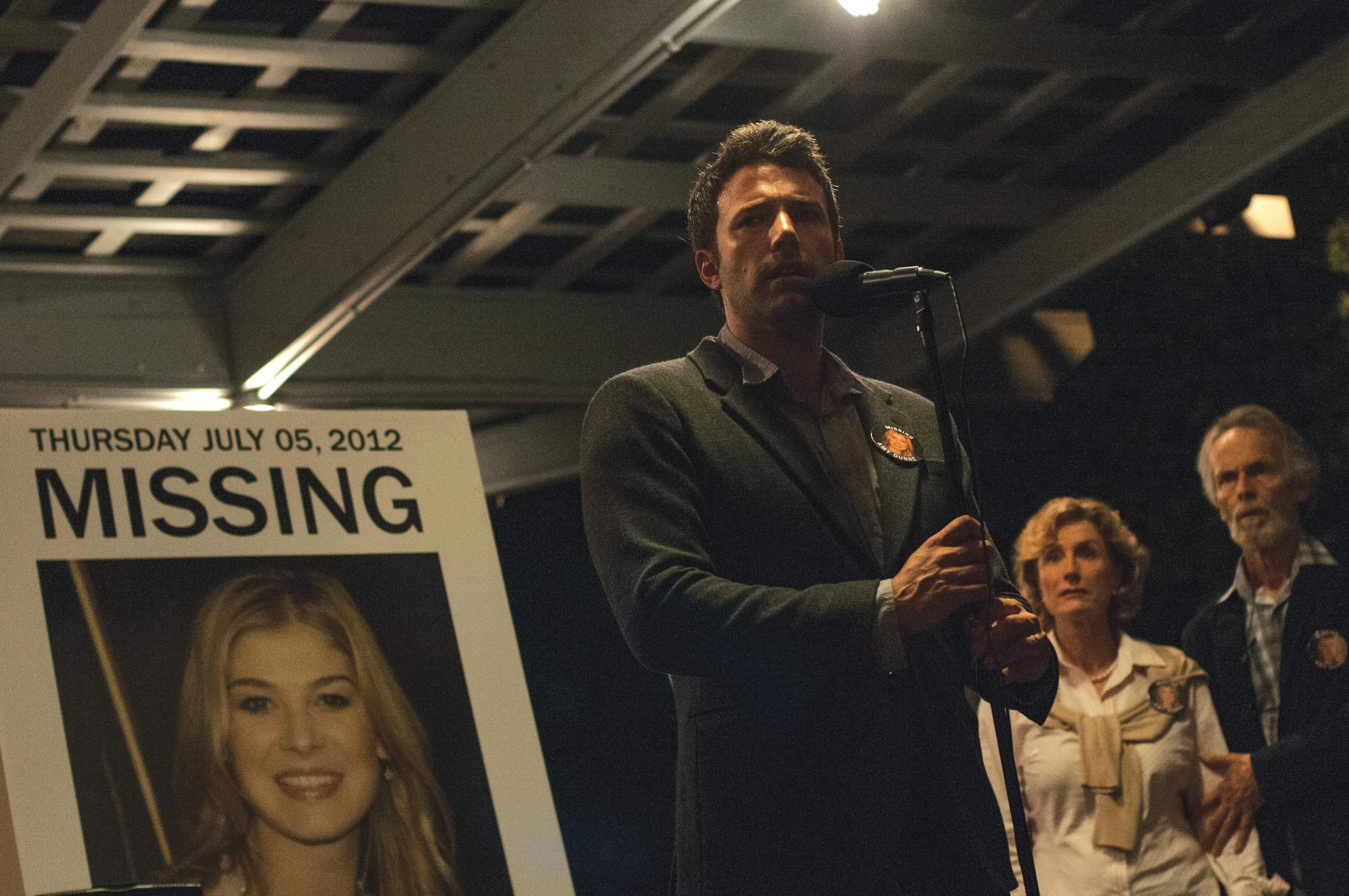

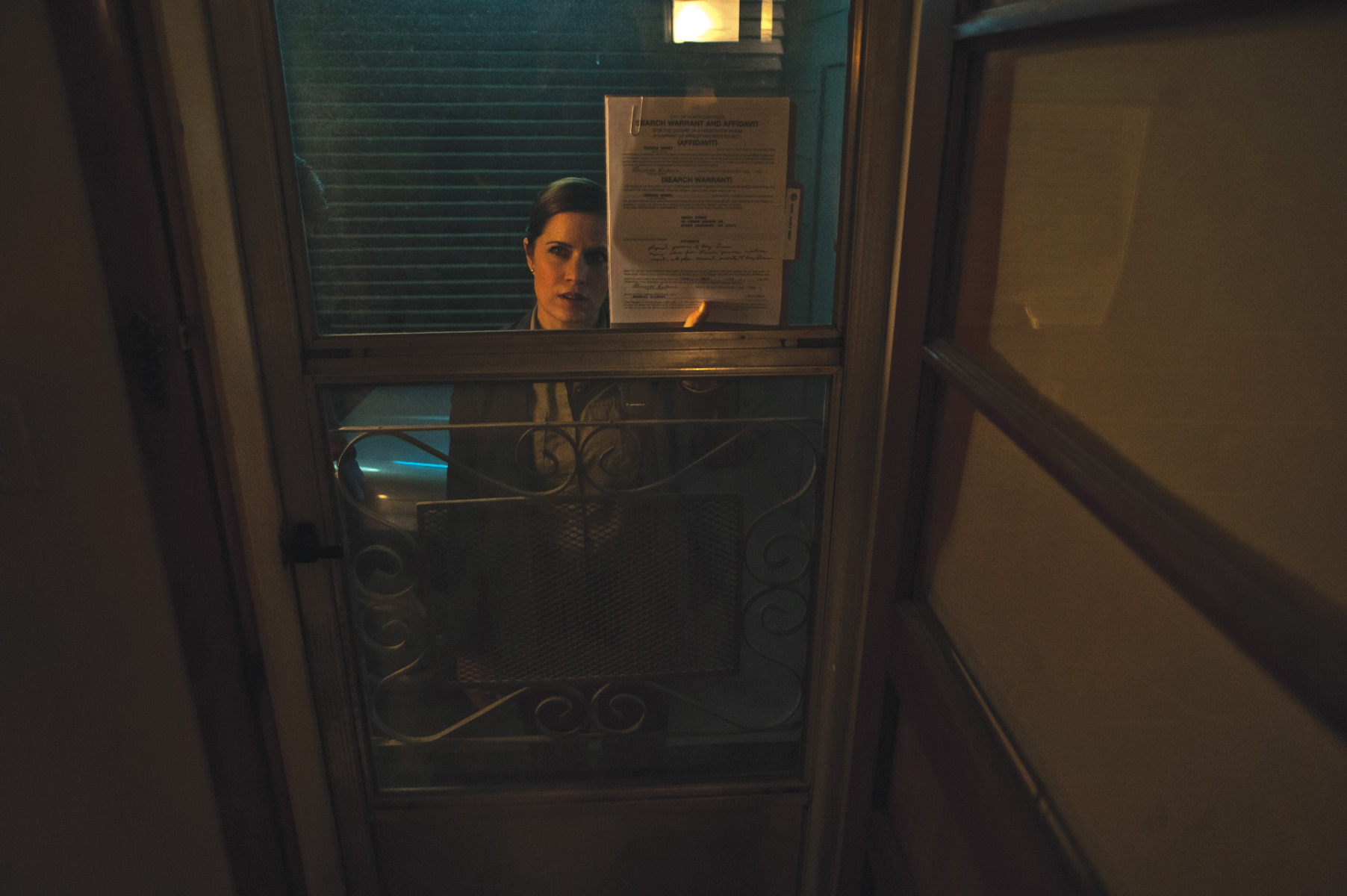

A series of mysteries form the core for the best-selling novel Gone Girl and its film adaptation, the subject of which is a married couple’s difficulties after they lose their writing jobs and move from the east coast to Missouri. The big question marks in Gillian Flynn’s popular book (as well as her own screenplay adaptation) are: to where has Amy Dunne (Rosamund Pike) disappeared, and is her husband Nick (Ben Affleck) involved? Other aspects relate to how well Nick will stand up to suspicions from the police and the media, and if the case’s very public exposure is ultimately beneficial or detrimental in resolving Amy’s fate.

Oscar-nominated filmmaker David Fincher describes Flynn’s novel as a “wicked look at marital resentments. While it’s at times a heightened thing, with moments that are deliberately absurd, I think Gillian’s book touched a nerve because it gave a voice to genuine concerns about cohabitation,” he shares.

“Nobody has been so profound in delivering this message, especially in so striking a way,” Fincher adds. “I felt it was both original and diabolical, while demonstrating how difficult it is to even imagine any relationship surviving the kind of scrutiny that arises out of the media side of things on a case like this.”

Fincher relied on a number of familiar behind-the-scenes collaborators to propel his first data-intensive (6K-capture) workflow, including director of photography Jeff Cronenweth, ASC, who began his feature career on the director’s Fight Club and more recently lensed Fincher’s The Social Network and The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo.

Cronenweth contrasts the way he illuminates Gone Girl’s protagonists with his approach on his first feature collaboration with Fincher. “In Fight Club you often can’t see the eyes on the main two guys,” he observes. “In addition to being unnerving, it was valuable in showing how shallow these guys were. Then, when we chose to bring the eyes out, it worked well in showing them as two facets of the same person. On this film, the intensity of the relationships between these people and the mystery surrounding it all was such that you really had to be able to see their eyes to have some idea of how this psychological chess game between this very dysfunctional couple played out.”

The RED EPIC Dragon 6K camera makes its feature debut in the film. “David and I were the first to use the Mysterium chip on The Social Network,” notes Cronenweth. “During the shoot on Dragon Tattoo we switched over to Epic when memory cards became available. After that I shot Hitchcock on the Red Epic.

“We stayed in contact with the Red group, and [president] Jarred Land is really good about embracing new ideas and advancements,” Cronenweth continues. “There were eight Dragons in existence when shooting began, and we had four of them. We brought Epics along as backups since we were away on location, but the Dragon was well tested before we got our hands on it, so we weren’t exactly guinea pigs. We treated the shooting like film, picking a single lookup table as you would a film stock, then creating the rest of our look with choices of lighting, art department and costuming.”

One new tool, the Meizler module, helped streamline shooting logistics, while another, Red’s Motion Mount, helped eliminate annoying digital artifacting like juddering. “When I look at the size of what is actually making the picture, that seems wildly compact to me,” Fincher describes. “But then you add all this other stuff and it becomes this Medusa; it drives me nuts to have all these cables velcroed to the side of the camera. The Meizler is a first incarnation of bridge building, from a quick-release battery – being able to hot-swap is great! – to the camera box itself.”

Fincher says the initial notion was to build a wireless video tap, auto-slate capability and make it bumper-to-bumper, from matte box back to battery, free of that after-market gack he so detests. “Lots of people got involved, and it wound up needing all kinds of I/O for 3D and synch boxes, but the most important part is the wireless 1080-p video tap; that is the only way to go for me,” he continues. The Ti PL Motion Mount, incorporating ND into a global shutter, was a major breakthrough. “I’m amazed by how it handles motion blur when panning, and we never had any issues with focus, either,” he adds.

Though long known as a strong proponent of previs, Fincher did not feel the need for it on this project. “There’s still no better way to prepare everyone for a complex and extremely exacting camera move than with an extremely intricate previsualization,” he allows, “especially if you’re shooting on a set like a plane, where sections need to get wilded away. But on location, it isn’t always necessary to spend a ton of money working out a ‘best laid plans’ scenario that may just wind up only helping prove Murphy’s Law.”

Cape Girardeau, Missouri, stood in as the story’s fictional town, with Fincher, Cronenweth and production designer Donald Graham Burt settling on locations that would serve as a palette upon which costume and set design could be based.

Cronenweth shot night exteriors at or below F2, which meant that gaffer Erik Messerschmidt could forego the usual 20-K–heavy augmentation.

“Instead we used gentler units to just boost the illumination, carrying from the existing location practicals,” he explains. “Shooting nearly wide open meant the first ACs had to be on their toes, though. There was still the occasional Condor needed when we had to edge or highlight a particular building, but not as much as you might think.”

Shooting took place across several city blocks, all illuminated by sodium vapor light. “As the globes age, the colors shift from magenta to yellow,” Messerschmidt describes. “The city worked with us to change out the older bulbs so the color was uniform all along the main street. The one exception was a courthouse. Since we couldn’t replace those bulbs, the art department painted the diffusers on all sixty of the existing fixtures to match. The locals liked the look so much, they didn’t want us to restore them afterward!”

Blue screen and green screen work – largely views out of the windows of the Dunne family home along with driving scenes – was facilitated through the use of Cineo HS fixtures employing LED white light sources, provided by DPS Inc.

“We needed a light that was adjustable in intensity, even at the ten–foot-candle level,” Messerschmidt adds. “Working with that little light, the flexibility is just not there working with either incandescent or Kino Flo. There’s minimal spill from the screen and less heat, and, most importantly, it gave Jeff a lot of options when it came to lighting the live-action part of the scene. We could just go back in and dial the appropriate amount of light to illuminate the green screen after he has the live action looking the way he likes it, instead of compromising the scene lighting in order to match the green screen exposure.”

Since Cineos can be run on a dimmer console, there is a record that can be called up when a need arises for matching. This was especially useful on the Dunne house interiors, built on stage with each floor a separate set, which meant lighting had to match precisely when taking a character up or down stairs.

“A lot of our night interiors just have a bounce into the ceiling or some back or edge light, which meant a very gentle touch when it came to taking away some of the ambient light,” the gaffer shares. “[Key grip Jimmy Sweet] drew on some serious ‘gripology,’ cutting the light off a wall or containing things.” Messerschmidt’s team also built numerous custom fixtures from LED ribbon provided by Lightgear, ranging from panels to tubes and lightbars, to enhance a variety of stage settings.

“We’re not glamour-lighting everyone like some TV shows do, because our story calls for a darker look,” he says. “But there were times when the story called for letting Rosamund look as gorgeous as she really is, so for those occasions we bring a little extra to the moment.”

Shooting strictly on primes, camera operator Peter Rosenfeld captured roughly eighty percent of the movie through four Leica Summilux-C lenses. “We stayed primarily between 21 and 40 millimeters; that was our sweet spot,” Cronenweth recalls. “The lenses are very sharp, and I shoot it as cleanly as possible. If there’s an occasional issue with skin tone or a blemish, that can be tackled in the DI or through VFX.”

The cinematographer attests that Fincher has never been one to invest in what he describes as ‘foreign energy.’ “Unless shakiness is a chosen and desired effect, we want all random camera movement gone,” Cronenweth confirms. “That means stabilizing the imagery, which, this time out, was often handled by artists in house rather than by one of our VFX vendors.” Longtime collaborator Digital Domain handled much of the effects load, which was also spread to Ollin Studio and Savage VFX. Work ranged from matte paintings to blood/squib work, which Fincher chose to avoid on set, owing to his admitted dislike of waiting for reset.

Some visual effects sequences required more TLC than others. “We don’t typically pre-grade for VFX, but the car interiors and driving exteriors had to precisely match,” relates [post house] Light Iron colorist Ian Vertovec. “Going this route really facilitated matters, so what we sent out to vendors was sure to come back color-corrected.”

Second assistant camera Paul Toomey managed data on set, while assistant editor Tyler Nelson handled ingestion and categorization, reviewing for any aberrations such as image softness. A 5K extraction of the original 6K imagery was made at the 2.40 aspect ratio, with a downconversion to 4K for release.

Another industry first for Gone Girl was the use of Adobe Premiere Pro CC for editing and conforming the entire feature. “The guys at Adobe were great about addressing our tech concerns on how to carry their editorial list over,” reports Vertovec. “With Fincher’s in-house team doing so much of the effects [largely through Adobe After Effects], we got new shots every day and traded lists back and forth constantly.”

Postproduction supervisor Jeff Brue saw to the film’s 6K pipeline concerns, which included real-time color-correction and review, accomplished via NVIDIA’s Quadro GPUs, with imagery requiring VFX being transcoded to DPX files. Edited footage was rendered through NVIDIA CUDA using the debayering process.

Light Iron had accommodated Dragon Tattoo’s 4.5K workflow, but in order to deal with the new 6K pipeline they had to soup-up their Quantel Pablo Rios. “Quantel helped with code in order to make this happen,” Vertovec states, “which really facilitated our being able to deliver a 4K end product. We worked in log, straight from the R3Ds to REDlogFILM.” The feature was edited from shard solid-state disks in 2304 × 1152, with a subsequent 1920 × 800 extraction to allow for stabilization and any reframing.

At press time, the digital intermediate process at Light Iron was still underway, with Cronenweth having cleared his schedule in order to remain as involved as possible with the DI. “I have a lot of trust in the people involved,” the cinematographer concludes. “Ian and Light Iron have done David’s last three shows, so he does one unsupervised pass to start with, then we look at what kinds of layering and VFX need to be added.” Or as Fincher simply declares: “Being able to view the finals in 4K is awesome.”

by Kevin H. Martin / photos by Merrick Morton

CREW LIST > Gone Girl

Dir. of Photography: Jeff Cronenweth, ASC

Operator: Peter Rosenfeld

Assistants: Jimmy Apted, Tucker Korte, Paul Toomey