Local 600 unit still photographers break down the hottest new trend in set photography – mirrorless cameras. By Pauline Rogers.

Shorter working hours, tighter sets, complicated setups, and no time for compliance all conspire to make today’s unit stills position a very challenging one indeed. So making an investment in a tool that may (or may not) make the job easier is a dicey decision, at best. If creativity and efficiency rise in equal proportion, why not take a leap?

Such is the big question surrounding today’s hottest trend in new technology for Guild set photographers: mirrorless cameras. And in reaching out to Local 600 members for their feedback, the first priority was to separate the wheat from the chaff, i.e., camera manufacturers are all striving for mirrorless (and therefore silent) systems, but not all mirrorless cameras are equal, or at least being embraced at the same rate of popularity.

For example, the name Hasselblad has always been associated with quality in the worlds of commercial, fashion and portrait photography, and the company’s Lunar is being touted as “mirrorless.” But we couldn’t find a single Guild member using it on set. Likewise for big-time consumer brands like Olympus, Canon, Samsung, Nikon, who are all trying to go mirrorless (with varying results). Even the classic brand, Leica, is touting its new SL camera as mirrorless, even though it’s not totally silent.

According to the working stills photographers with whom we talked, there are two main mirrorless units impacting the film and television industry: the Sony A7s and the Fuji XT1. What sets them apart? And are they worth the gamble?

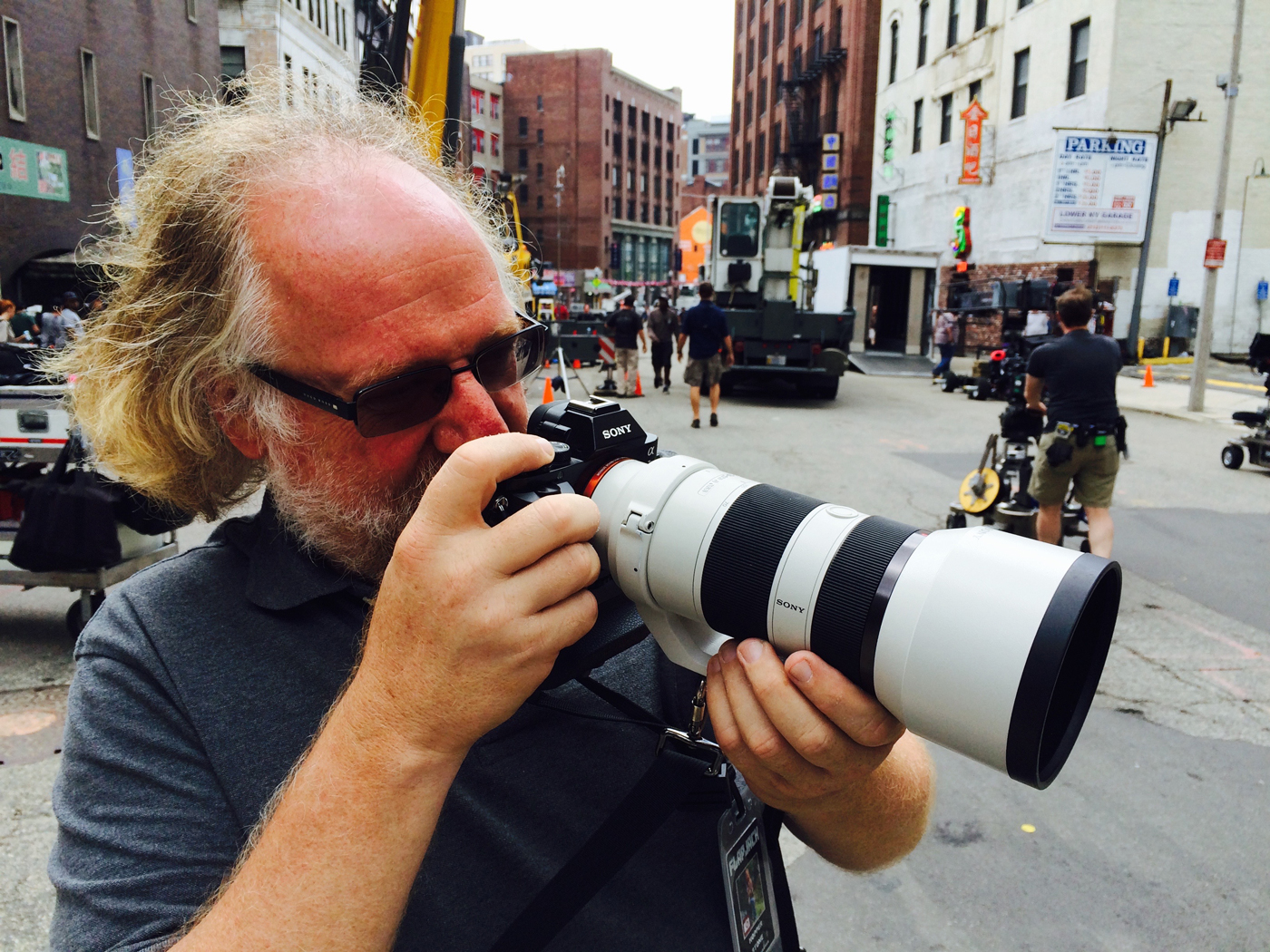

Hopper Stone emphatically describes the cameras in the Sony A7s line as “game changers.” He’s covered The Boss (Universal) and Ghostbusters (Sony), as well as one-third of New Line’s Vacation with a A7s, using Canon lenses with an adapter. It’s silent, compact, lightweight, has great image quality and can see in the dark.

“It will go to 12,800 ISO without breaking a sweat,” Stone describes. “You can go higher than that, but then you have to get under the hood with some good noise reduction to work on the files.

“On Ghostbusters, Production had me print up 50 photos to 11-by-17 inches for a presentation to the Foreign Press,” he continues. “None was shot below 3200 ISO, several were shot at 12,800, and the image quality never looked worse than 800 ISO negative. The image quality at as low as 100 or 200 ISO is mind-blowing.” (The A7sII will go to 25,600 with the same image quality as the A7s.)

For Stone and many others, the absolutely silent mode is key.

“An actress actually asked me to say, ‘Click, click’ when I was doing a prop still with her so she would know when I was shooting,” he laughs.

Elizabeth Sisson works on Chicago Med, a show that takes place in an ER with very tight spaces. “The sound guy would give me the stink eye even with the blimps on my Canon,” Sisson recalls. “So when Elizabeth Morris, on Chicago Fire, told me about the new Sony, I put a bid on it at AbleCine Tech and won! The first day I used it on set I was in a very tight and very quiet room, and the ISO was over 800. The sound guy didn’t say a word, and the actor didn’t even notice I was in the room!”

The unit’s size, weight and speed are all key factors for early adopters like Stone and Sisson. Carrying a Canon Mark IV D, for example, with long lenses and a large blimp, can get heavy. “I’ve been having significant back pain while shooting 16-hour days,” describes Elizabeth Morris. “Since I switched, my back pain is almost non-existent.”

“It can be tiring holding a blimp all day, especially during long takes and setups that require long lenses,” admits New York-based shooter Sarah Shatz. “The Sony body is light and the lenses are fast. Even with 70-to-200–millimeter zoom at F4, the camera is like a computer, so it doesn’t really matter. Changing lenses is no longer time consuming. So we can work quickly on the set.”

Flexibility also comes into play with Sony’s unit. Morris shoots one-handed while utilizing the LCD screen/monitor. In addition, the LCD screen can move, so she is able to adjust if she is shooting high or low and can still see the screen. Morris says she’s getting a lot of one-handed shots unavailable to her before.

Stone has learned a great trick for his one-handed work. “I’ve added a vertical grip that holds two batteries,” he shares. Like Morris, he loves the LCD rear screen that flips out. Stone often operates from the screen, hiding around corners, holding the camera out a bit. “If the film cameras are smashed together, I can usually squeeze my camera in somewhere and just shoot by looking at the rear screen,” he adds.

Many Guild photographers are hooked on the unit’s low-light capabilities. “Twelve megapixels allows for extraordinary low-light shooting,” Morris adds. “The ISO range is significant and has allowed me to shoot coverage I otherwise would never have been able to capture.” The camera has one more stop of usable low light, allowing shooters to go as far as ISO 25,6000 before having to perform massive noise reduction.

Add image stabilization and an impressive amount of megapixel storage in RAW, and you’d think you’ve got everything. But there are still drawbacks – Morris says battery life is so short, she has to keep numerous backups on hand. [Sony reps say battery consumption has improved for the A7sII, and they’ve added a USB cable to either run the camera or recharge batteries on the run.]

But, Shatz, laments, “the digital viewfinder feels like I’m staring at a tiny computer, so there is more eye fatigue. Working in silent mode you can’t do continuous shooting, which is essential for action shots, and helpful in general, when you can shoot only a limited number of takes. Also, in silent mode, the camera can’t handle the buzz of LED lights, so in scenes lit with LEDs, the pictures come out with striated lines.”

Stone has a few other issues. “The auto-focus system is not as good as Canon’s or Nikon’s, although the A7sII has shown a definite improvement,” he says. “The standard zoom lenses for this camera are F4.0. And, like other Sony cameras, regardless of the model, they all generate the same file names – so if you are shooting with two bodies, it can get a bit challenging when you are downloading the files into one folder. A firmware update that would allow the user to generate custom file names would be very helpful.”

All of the Guild shooters using Sony’s mirrorless system have similar problems in Lightroom, where the canned color profiles for image processing aren’t great. Stone has resolved this by creating custom profiles using an X-Rite ColorChecker Passport.

“It’s a tedious process, which luckily you only need to do once,” he explains. “After that, I have my defaults in Lightroom set to automatically apply the profiles upon import. I supply the profiles to whichever lab is doing the asset management. This way the colors carry over.”

When Frank Masi started researching his move to mirrorless, he talked to shooters like David James and Scott Garfield. “They both told me how beautiful the glass was on the Fuji XT1,” Masi relates. “To me, lenses are more important than the body. The lenses, after all, are my eyes!” Barry Wetcher, who recently started using the Fuji XT1 on Dreamworks’ The Girl On the Train, agrees with Masi. And he loves Fuji’s zoom lenses, “which open to 2.8.”

Heartened by the Fuji recommendations, Masi chose to use the new camera on The Circle, which comprised “a lot of shooting inside small spaces, mainly offices and cubicles,” he describes. “I started Day One with one body and two lenses. After the second day, I quickly stopped by Samy’s Camera and bought a second body.” For Masi, two bodies with a 16-55–mm F2.8 (equivalent to 24-70 mm) and 50-140–mm F2.8 (70-200–mm) lens allowed him to dance around the intricate moves that cinematographer Matthew Libatique, ASC, had designed.

“The XT1’s feel like they weigh about three pounds each – and with a BlackRapid Camera strap, you don’t even know they’re on your shoulder.”

As with any truly silent mirrorless system, the lack of a blimp offers instant results. “At first I was a little concerned about not having the blimp to hide behind and the actors having full view of me, but I quickly realized this was not an issue,” Masi admits. “Tom Hanks quickly noticed that I was shooting without the blimp. I showed him the camera and let him fire off a few frames, and he seemed to think it was pretty cool.”

Clearly, mirrorless cameras allow for more intimate shooting. “The electronic shutter’s complete silence has enabled me to shoot an extremely quiet and emotional therapy scene that normally might not be possible due to sound coming from the blimp,” Wetcher recalls.

“The greatest feature of the Fuji XT1 is that I can shoot with the camera to my eye and see the stop change in the viewfinder as I open up or stop down,” Masi adds. He shoots everything other than his focus manually. He changes F-stops and shutter speeds constantly. And, of course, not having to open the blimp throughout the day is a plus.

Guy D’Alema says exposure adjustment is easier on the XT1. “Coverage we did on Containment called for an interior scene where the talent went from standing by a window to the back of the set with minimal lighting,” D’Alema recalls. “With a camera in a blimp I would have to have made two passes – one set for the brightly lit part of the set and then the second for the darker part.”

The tilt-out monitor provides a distinct advantage. “This was a major plus, as I was able to match a floor shot of the talent without having to lay on the floor and try to see through the blimp,” D’Alema adds. “I was able to comfortably sit on an apple box and shoot the floor shot that matched the camera angle they were shooting.”

While many new users of the Fuji camera choose to use Fuji lenses, some add an adapter for a wider range of brands. “I use a Metabones Speed Booster Mount, so I can use my Nikon lenses,” D’Alema continues. “I get a full range of lenses without the 1.5 magnification factor that the camera sensor creates, and it adds one additional f-stop to the lenses. So, the 70-200–mm F2.8 operates as a 70-200–mm F2.0 lens, maintaining the focal lengths and increasing one stop of light – helpful on low-light sets and night exteriors.

“With the Metabones Speed Booster I have to focus manually, so critical focus within a scene is more reliable than the auto-focus options on most still cameras,” he adds. “It allows for ‘focus peaking’ much like the first ACs use on the production cameras for critical focus situations.”

Recently, D’Alema has added the dedicated Fuji glass to the system he owns – 18-55–mm F2.8 and 50-140–mm F2.8. This allows for control of remote features – even operating the camera from his smartphone (focus points, capture, aperture, ISO, white balance) when placing the camera on a jib or tripod. It also enables the “face detection” feature (for portrait applications) with specific eye focus – and enables auto focus.

With Fuji’s XT1, shooters also get high resolution (16-MB sensor) and color and detail every bit as good as on larger file sizes from the DSLR cameras. The dynamic range is impressive.

But, like any of the new mirrorless units, there is a downside.

“Don’t drop it,” Masi says about the Fuji, with its super-small footprint. “I was shooting a night shoot in the L.A. River. It was a long day, I was tired and, well, I just dropped my XT1 with the 50-140–millimeter zoom lens. It fell about eight feet, sheared the lens right off the body and destroyed both the body and the lens. It was a total loss that, fortunately, was covered by my Amex protection program. I’d recommend always bringing a non-mirrorless body as a backup.”

Guild shooters also point to the learning curve with the new mirrorless systems.

“My experience is that the menu controls on the back of the camera are very small,” Wetcher explains. “I sometimes struggle to hit the correct button when my eye is in the viewfinder. Either my fingers are too big or the controls are too small!”

And maximum ISO can be drawback. “RAW is 6400,” says D’Alema. “At full silent. The camera will go beyond, but you have to use the mechanical shutter mode, and it is no longer silent [in that mode].”

D’Alema concludes about the new mirrorless trend: “It’s an additional camera body that has specific use and applications,” he reflects. “[Mirrorless units], at this time, don’t offer enough to replace the DSLRs in sound blimps that most shooters have used. They’re ideal for normal lighting situations, and their light weight saves wear and tear on your back and shoulders. But they also still have issues with moving subjects and tracking.”

Bottom line for unit stills members thinking of taking the mirrorless leap? Invest wisely and always carry a backup.