The penultimate episode of cinema’s greatest franchise has arrived. So which is more surprising?: who really are The Last Jedi’s heroes and villains, or its indie creators with an edgy new vision?

You’d have to go back to Shakespearean literature to find a more tangled family tree than that in Star Wars, the epic sci-fi adventure series sprung from George Lucas’ imagination more than four decades ago. The original trilogy (Episodes IV, V, and VI) revealed its naïve young hero, Luke Skywalker, to be the son of his hated nemesis, Darth Vader/Anakin Skywalker, and the beautiful young princess fighting empirical tyranny was Luke’s twin sister.

Star Wars’ prequels (Episodes I, II, and III), which highlighted the backstories of Luke, Anakin/Vader, Obi-Wan (Ben) Kenobi – the ancient Jedi knight who trained Anakin – and Emperor Palpatine/Sith Lord, were also steeped in moral ambiguities, and Lucas could have ended the series with Revenge of the Sith, which precedes the shared journey of father and son – the former’s fall from grace and redemption, the latter’s passage from naïf to savior – completed in Return of the Jedi. But then came The Force Awakens (Episode VII) a decade later, with a new set of heroes and villains who all possess equally tenuous family connections. The Walt Disney Company has released only a few trailers for The Last Jedi (Episode VIII); and given the lack of information they provide, narrative surprises – who are Rey’s parents? Will Kylo Ren go from dark to light? Does a grizzled old Luke turn away from the Force? – are guaranteed.

What may be more surprising than any story twist was the methodology writer/director Rian Johnson and his longtime cinematographer Steve Yedlin, ASC, chose. Joined by 2nd Unit DP Jaron Presant (who worked on all three of Johnson’s previous indie features), and Production Designer Rick Heinrichs (whose credits include Tim Burton and Coen brothers films), Jedi’s creative team took an approach steeped in Johnson and Yedlin’s indie roots: rigorous planning of the broad strokes so that flexibility on-set could focus on fine-grained finessing.

“I don’t want to downplay the massive scale and excitement,” observes Yedlin about being part of the Star Wars franchise. “But this really felt like the family was back together: another Rian Johnson movie. It wasn’t a ship steered by a faceless corporation.”

Yedlin adds that, “even before prep started, Rian said there was no pressure to make this look like another movie in the franchise. Moreover, he was clear that our style of working and our aesthetics would not have to change because it was Star Wars. Rian wrote the script, it was his vision, and we really approached everything as we’ve always done together, which is not to sledgehammer the movie into a simple visual box, but to design each scene as needed.”

This creative mind melding has allowed Yedlin to explore his prime artistic strengths –lighting and color rendition. The cinematographer says Johnson is very collaborative in both lighting and camera, “but whereas Rian is hands-on with the specifics of lensing, when it comes to lighting, what he gives me is much more subjective. He trusts me to take his conceptual ideas and bring them to life in the details.”

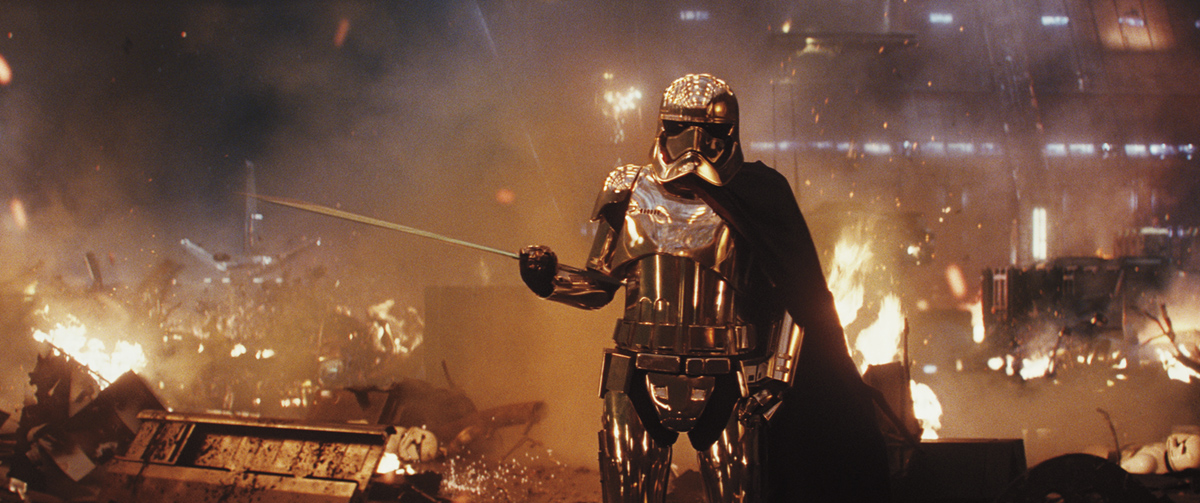

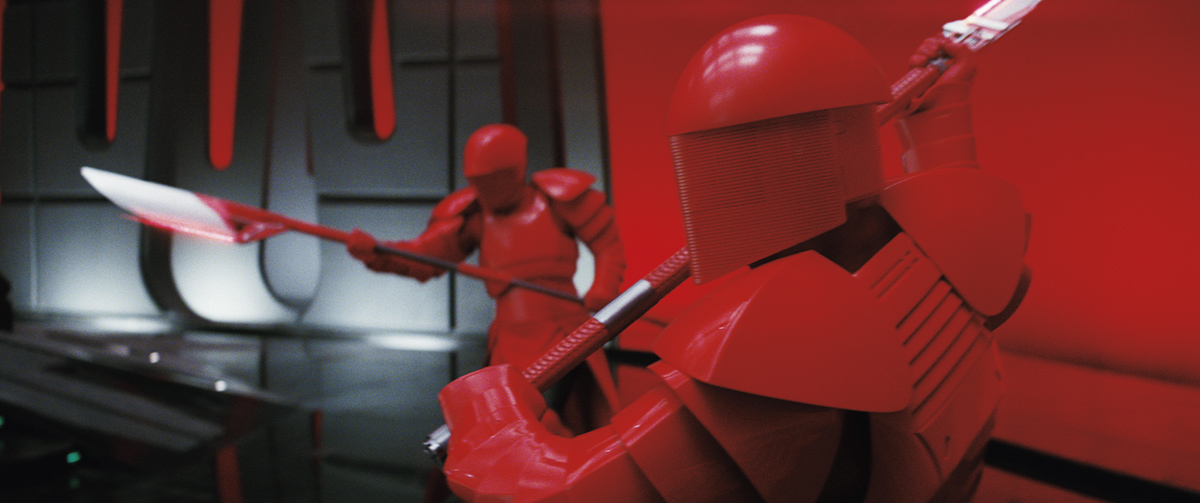

One such example from Jedi’s second trailer involves a black-helmeted, black-gloved figure (Kylo Ren, or perhaps Snoke?) picking up a lightsaber from a black glossy floor. The entire background is filled with a deeply saturated red light, providing a stark (and unsettling) contrast to the foreground. A voice-over intones about someone with “raw, untamed power….”

Yedlin says the scene was discussed at length between him, Johnson and Production Designer Rick Heinrichs. “We came up with a specific color of red and a physical way to do it that we all liked,” he shares, “and then made a commitment not to hold back in any way. It’s a good example of how carefully color was designed in this movie.”

Heinrichs says that the color palette in Star Wars is often restrained, “in keeping with the black-and-white concept of a ‘space western.’ Used sparingly, [red] can have a huge emotional impact, and Rian and Steve’s use of the color as both a ping to the Emperor’s guards in Return of the Jedi and of the status of the environments in which the color occurs looked spectacular.”

Yedlin, a highly technical shooter by anyone’s bar, says his facility for color science dovetailed with the aesthetic color design of the movie through the use of a global show LUT he created that allowed him to “be confident I could use daring colors or exposures and know that the result would provide the intended painterly look with very little shot-to-shot color grading.”

Jedi was captured primarily with Kodak 5219 (in Panavision’s XL2 cameras) and with ARRI ALEXA (using both ARRIRAW and ProRes4444). Film and digital elements were brought in to a show-specific neutral space using LUTs designed by Yedlin and then, from the neutral space, all footage received a single show LUT, which emulated the look of traditionally contact-printed film.

“We couldn’t have done this five years ago on Looper,” he continues. “At that time, color grading was tethered to film recording and could only visualize how the footage would look when you filmed it out, so the process was predictive, not purposive. On Jedi, the neutral space LUTs brought the various cameras together, and then the show LUT gave us our look: very similar to the look we would have gotten if we’d have contact-printed film negative, even though we didn’t actually print anything.”

Yedlin says the film elements were brought into the digital neutral space using a Scanity scanner with custom/fixed settings that pegged digital code values to physical negative densities. The digital footage was brought to the neutral space with a LUT that mapped (the ALEXA’s) LogC (color space) to the same densities and colors as the film scans.

The cinematographer lit the movie to his global show LUT much like a traditional combo of camera negative and print stock. An example is that the “very bold red we designed [for the aforementioned scene],” he expounds, “would have a ‘filmy’ painterly feel. In traditional contact printing, the reds go a bit yellow and can’t be both very bright and highly saturated at the same time, unlike the customary video/electronic palette, which has more magenta reds that might be both bright and saturated. Having the color science figured out upfront meant we didn’t have to build this stuff from scratch in post. It was all there from the beginning.”

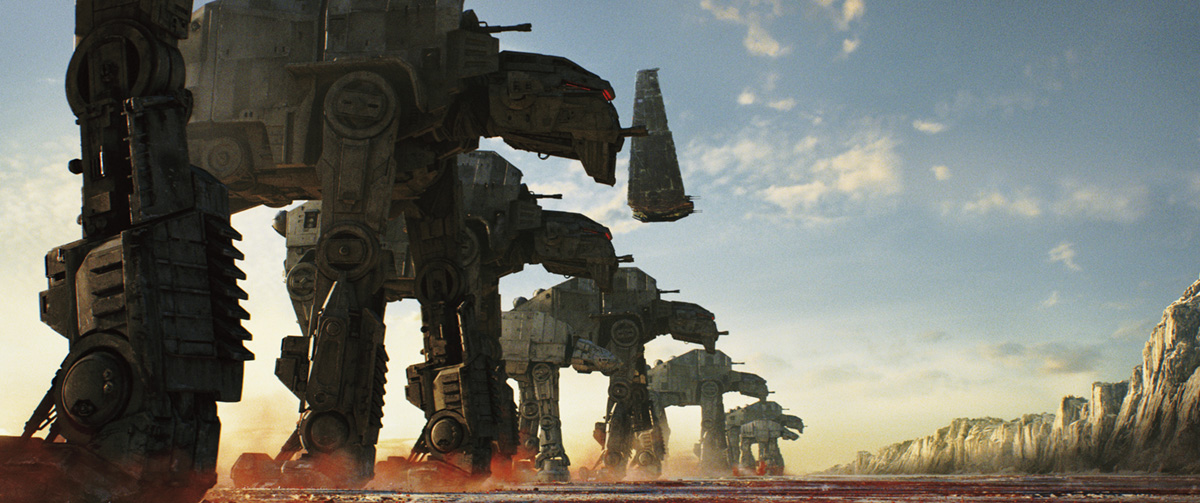

Building an in-camera foundation also factored into Jedi’s visual effects, which, according to VFX Supervisor Ben Morris, with ILM in London, numbered close to 2000 shots.

“Rian was coming from a traditional [film] background,” Morris recalls, “and he wanted to do as much as he could practically, which is a recurring theme of many filmmakers these days. I showed him some of my previous work [with Framestore], with the goal of showing how an effective mix of practical and digital effects can keep the audience guessing.”

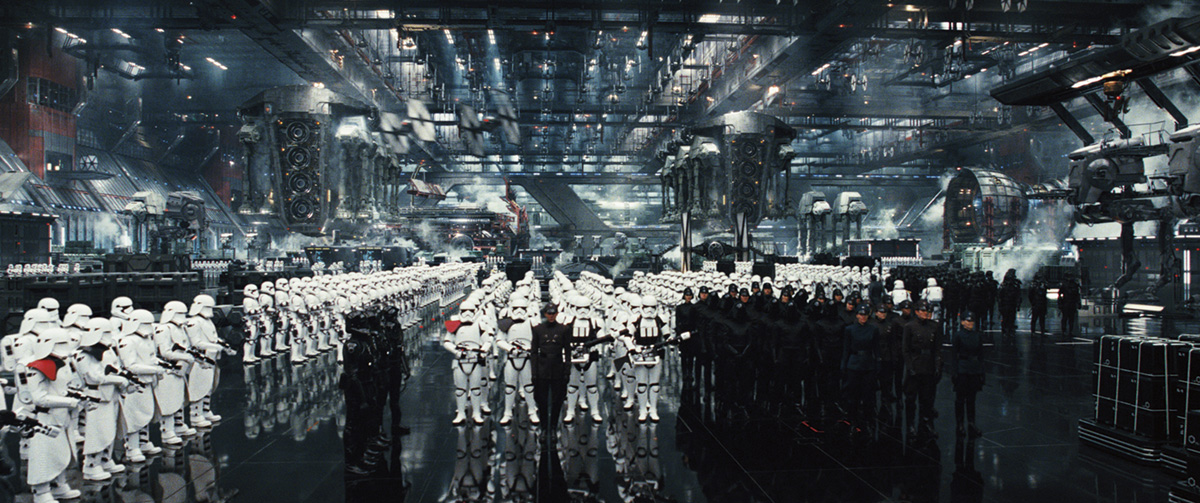

Morris, who worked as VFX Supervisor on The Force Awakens (Roger Guyett was lead VFX Supervisor as well as 2nd Unit Director), says there is a visual language in Star Wars that many people on the franchise grew up with, “myself, J.J. [Abrams], Rian, and Steve included. The goal is to evolve that language without disconnecting from it,” he observes.

“Contrary to popular belief,” Morris laughs, “[digital artists] prefer real photographed elements as a basis for VFX shots. That helps ground the shot and make the VFX seamless. Rian, Steve and I lobbied to capture as much as possible on location.”

One happy marriage, seen in the trailer, is a long wide shot (alluded to in Rey’s vision in The Force Awakens) of a Jedi temple in flames, with Luke and R2-D2 in the foreground. The temple is where Luke had trained a new generation of Jedi, including his own nephew, Ben Solo, who would later become a Dark Side leader with followers from the Knights of Ren.

Morris says the striking night shot was done on a sound stage with foreground elements lensed against blue screen, and embers and wind machines provided for foreground texture.

“The background had a combination of 3D environments, matte paintings, effects simulations and quite a lot of practical elements,” Morris describes.

Regarding concept art for the sequence, Heinrichs explains that “physical models have always played an important part in our development process. And while technology that truly places the viewer within a walkabout virtual space is impressive, it’s not yet agile or efficient enough for practical set visualization discussions.”

Still, Heinrichs discovered on Jedi that “the flattened environment spheres” exported by many 3D modeling programs can be reconstituted by an iPad app (like Kolor Panotour Viewer) and the tablet’s onboard technology into a manipulative window on a virtual environment.

“This allowed Rian, Steve, Ben, and myself, with an iPad, to stand in the middle of a set on stage before it was built, as well as view proposed VFX elements and extensions while the set was being shot,” he explains. “This off-the-shelf tech gave us the confidence on the burning temple set to refine the blend between physical and digital elements, using foreshortened ground rows and textures to extend the reach of what is illuminated on stage into the background.”

Yedlin says that to create the firelight on characters’ faces for the temple burn and other fire-lit sequences, he photographed real fire in prep, and then calculated corresponding HSI chromaticity coordinates to program into the arrays of ARRI SkyPanels (more on that later) that he had worked out with Gaffer David Smith (Avengers: Age of Ultron, Guardians of the Galaxy). Yedlin adds that this was before the existence of the SkyPanels’ new “x, y” mode, which would have made the R&D process more streamlined.

“The way that the units flickered depended on the size of the array,” Yedlin recounts. “In one case we might have a 20-foot by 20-foot SkyPanel array hanging from a crane and in another just a single panel. The larger the array, the harder the attack, the faster the oscillation and the wider the contrast range required of each individual luminaire in order for the combined effect to feel right.”

Interactive lighting was another key aspect of Jedi’s look, particularly for the many moving vehicle scenes in space or in planetary atmosphere. Yedlin and Smith created a hemispheric dome – 360 horizontal degrees by 180 vertical degrees – filled with 250 ARRI (LED) SkyPanels that were all controlled through pixel mapping. “For example,” Yedlin explains, “an actor in a ski-speeder cockpit may be completely wrapped in sky-colored light one moment, then in the next, the shadow of a passing vehicle might block some of the sky with three-dimensional realism, and then the light on the actor’s face might change realistically as she flies through a fireball and passes oncoming laser bolts.

“I know a more popular method is to play back a photographed or CG-rendered scene on an LED video screen,” he adds, “rather than using coarse 3D-rendered shapes pixel-mapped to LED luminaires. But we felt that was limiting for multiple reasons: Unlike our agile method that uses motion-picture luminaires, that LED-video-screen method makes it slow or impossible to change the colors or the timing of the scene quickly on set. Also, LED video screens can’t rival purpose-built luminaries for contrast and brightness output, and [unlike luminaries] LED video screens are not designed for their emitted light to be the correct color, even if they appear the correct color when viewed directly.”

An example Yedlin cites is an agile flying vehicle executing a barrel roll, not unlike an airplane in the sky. “In real life, the lighting shift is not very pronounced when the airplane’s cockpit rolls from facing the sky to facing the ground. But in a movie you want to enhance the dramatic effect. Our SkyPanel dome allowed for highly flexible and interactive variations of color and intensity.” Yedlin is quick to add that the dome itself was never used as a hard light projecting sharp shadows. “Interactive hard light, such as a shifting sun, was created by a light on a crane inside the dome, not by the SkyPanel array itself.”

Jaron Presant says his 2nd-unit work with Kylo Ren’s TIE fighter was also shot in Yedlin’s SkyPanel dome because the correct shadows and light interaction were essential to tie physical set elements into the CG world. “We built extensions to the fighter set piece to mimic the large wings of Kylo Ren’s TIE fighter,” Presant recounts. “We put cues into the dome to mimic the blocking of ambiance by the other ships that Kylo passes as well as the missiles firing and explosions. The interaction of the light on Kylo is what helps to blend the physical sets into the CG world around them. It was a huge key in making these worlds feel real.”

Heinrichs references an elaborate set built for Jedi that takes place on Canto Bight, a casino-like planet that not only serves as an opulent playground for the wealthiest members of the galaxy but also a place where black-market weapons are sold to any taker.

“[The Canto Bight scenes] reveal a gray moral line that had heretofore seemed mostly black and white,” Heinrichs adds. “Steve used a variation of his SkyPanel dome for a casino bar scene that had a huge window. [Yedlin’s] goal was all about creating action and motion with light, color and shadow, and the results were quite remarkable.”

A main visual reference for Jedi was The Empire Strikes Back, “not in any direct way, but more as a shorthand for an aesthetic Rian and I share,” Yedlin observes. “Empire is the most daring [Star Wars] film cinematically speaking. There was always an idea behind the lighting, which is very much what Rian Johnson is all about. One of many examples would be the scene with Leia and Han in the hallway [on Hoth], where their faces are completely dark. The lighting was so evocative, thematically, of the space the characters were in, and that’s something we really love.” Although most of the team’s referencing of The Empire Strikes Back was for underlying principles as opposed to literal technique, an exception was that Yedlin dug out color charts from Empire’s production negative – Kodak 5247 – to help inform his LUT creation.

Heinrichs says Johnson was aware of the comparisons people would make to a second Star Wars episode in a trilogy, and rather than “copy Empire in any way, shape or form, we should dig into the foundation of what we liked about it, and build something fresh.”

Building lighting into Jedi’s sets was a big topic of preproduction conversations between Heinrichs and Yedlin. “This is where our digital models became so helpful,” the designer continues, “to help Steve and his team figure out where to place their lights, rather than come in after the set is built and start cutting holes.

“Obviously with Star Wars you just can’t put [any lamp] in a scene because it’s not part of that world,” Heinrichs adds. “But there is a language to the built-in lighting we’ve seen throughout the series – the photon-producing type panels of various shapes and design, for example. The closest reference I could make would be the Ken Adams set from Dr. Strangelove – a large overhead source that illuminates with clear intention and lets everything else fall off. We accounted for that in the architecture of our sets – which would often include frosted Plexiglass – and that allowed Steve to manipulate light seen in the frame.”

Presant says that for the Canto Bight sequence, Johnson and Yedlin wanted two basic colors of light for the practicals: a rich gold color and clean white.

“Since we were committed to using practical locations and sets as much as possible,” Presant explains, “there were location practicals that had to conform to this golden color. We developed color correction to take the sodium vapor practicals at the location to the designed golden color. But with that in mind, any other lights we added needed gels to invert that correction.

“We used the Alexa as a colorimeter,” Presant adds, “comparing color charts illuminated with a variety of gels to arrive on a very specific gel package to shift any other lights we might use to the output we were looking for, whether clean white or golden. Then we applied that package to all the lights that played in the sequence. The end result was an environment that commits fully to these two types of practicals but that is grounded in reality.”

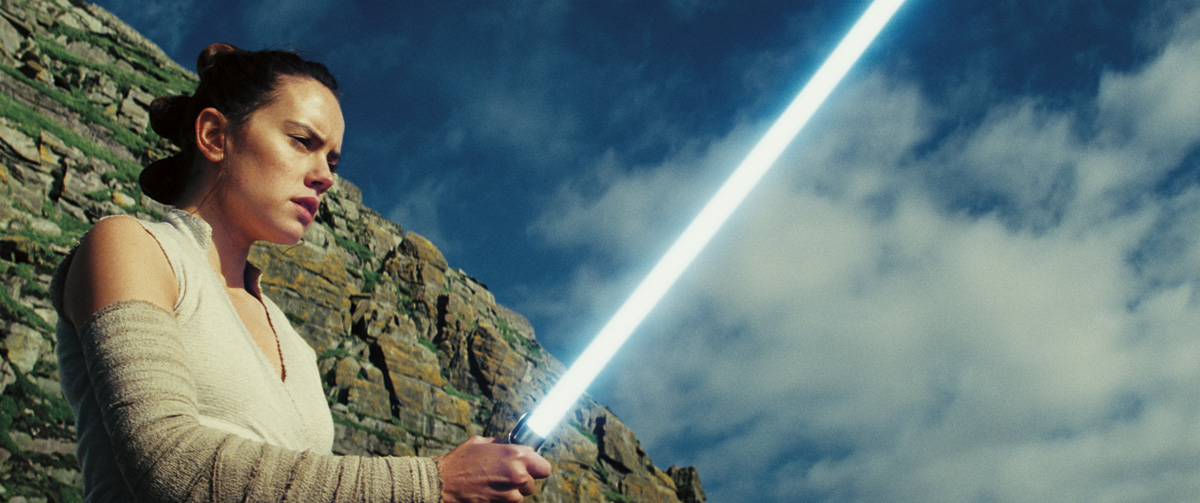

One look at the trailers makes clear some of Jedi’s most compelling moments will occur on the oceanic island of Ahch-To, where Rey has tracked down an exiled Luke Skywalker. It’s also where Johnson and Yedlin were, perhaps, closest to their indie roots.

“The day exteriors [on the island] account for the least predetermined lighting [in the film],” Yedlin states. “Employing a large filmmaking apparatus – like giant lights on cranes – wasn’t practical because most of the locations, especially Skellig, were either difficult or impossible to access, due to logistics or restrictions. Plus the weather was constantly changing, so the overall approach was similar to a low-budget indie movie – given the circumstances, we work to make each shot look as good as we can and don’t try to change the world!”

Presant points to a dramatic shot of Rey seen in the trailer, a night sequence that incorporated an exterior Irish location and a set piece in London.

“With our day and dusk-for-night work, our goal was to try to attain the low-contrast look of night,” he reflects. “We waited for the sun to dip and the luminance range of the scene to flatten. Then we shot the wide of Rey that looks toward the water. Back on stage for the reverse coverage, we matched all of our ratios using a large overhead Flo-bank array and shaping with a 20-by-20 soft box with Skypanels. We worked with what nature gave us and then used our resources to build out the sequence back on stage. But it all began with real natural light.”

One last interesting note about The Last Jedi pertains to optics. While the movie was primarily shot in anamorphic, using Panavision G-Series (full set), C-Series Close Focus 50 mm, the AWZ (40-80 zoom) and some other anamorphics, Yedlin and Johnson also mixed in spherical lenses (a 19-90-mm Primo Compact Zoom and an assortment of Primo primes).

“We wanted the idiosyncrasies of anamorphic – oblong bokeh, curved distortion, its characteristic flares, and the anamorphic ‘egg’ [the lenses’ inability to focus at the top and bottom of the frame],” Yedlin details. “But there were times that we either didn’t want those idiosyncrasies – like if an actor’s face was going to be in the blurry part of the ‘egg’ – or when we needed to do a rack focus to closer than an anamorphic can focus. We also sometimes used spherical simply because VFX requested it: either because they wanted the extra image padding outside the framing area or because they wanted a more technically pristine lens.”

Heinrichs, who has mapped out huge franchise projects and small indie films, says the scale of The Last Jedi had no bearing on the production process. “We had 160 sets to build, and initially I had some concerns,” he concludes. “But it didn’t seem to faze Rian or Steve in the slightest. This was one of the most creatively efficient movies I’ve ever worked on, and that may be attributable to their roots [in independent film] and the ability to get where they need to go creatively without throwing more money or time at the scene. The most amazing thing I can offer from this experience is that the movie Rian told me about – two years before we started shooting The Last Jedi – is the one everyone will see up on the screen.”

by

DAVID GEFFNER

photos/framegrabs courtesy of

LUCASFILM, LTD

LOCAL 600 CREW

Director of Photography

Steve Yedlin, ASC

Still Photographer

David James

2nd Unit Director of Photography

Jaron Presant

ADDITIONAL CREW

A-Camera Operator: Gary Spratling

A-Camera 1st AC: Simon Hume

A-Camera 2nd AC: Tommy Holman

B-Camera Operator: David Hamilton-Green

B-Camera 1st AC: Lewis Hume

B-Camera 2nd AC: Archiebald Muller

C-Camera Operator: Angus Hudson

Additional Camera Operator: Tony Jackson

IMAX Camera Operator: Peter Field

IMAX 1st AC: Dean Thompson

IMAX 2nd ACs: Alex Collings, Russell Torode

IMAX Technician: Stuart MacFarlane

Additional 1st ACs: Kenny Groom, Spencer Murray, Ryan Taggart

Additional 2nd ACs: Adam Dorney, Kat Spencer, Calem Trevor

Central Loader: Alex Teale

Camera Trainees: Jake Powell, Sam Taylor

2nd Unit

Camera Operator: Jason Ewart

1st AC: Julian Bucknall

2nd AC: David Pearce

Camera Trainees: Guido Cavaciuti, Toby McKay, Angus Mitchell

Additional DP: Jean-Philippe Gossart

Additional 1st: AC: Adam Coles

Additional 2nd ACs: Alex Bender, Felix Pickles

Central Loader: Morgan Spencer

Cover Photo by Jonathan Olley