HBO’s Game of Thrones demands (and delivers) VFX spectacle beyond other small-screen fare

A Song of Ice and Fire is the title of novelist George R. R. Martin’s series of runaway successes in fantasy fiction, one that for many seems destined to eclipse Tolkien’s and other past masters’ works of that genre. From the seminal book A Game of Thrones onward, Martin’s universe has proved immensely popular, and even though HBO’s series began airing in 2011, development began more than four years earlier, under the stewardship of David Benioff and D.B. Weiss.

The series balances strong production values with a combination of eye-opening and invisible VFX, but all elements are carefully subordinated to the epic storyline. For director Michael Slovis, ASC, who helmed the first two episodes of the new season, the production – based in Northern Ireland – differed markedly from a domestic TV shoot.

“During my episode prep, producer Chris Newman and I drove an hour out of town,” Slovis recalls. “Then we transferred to a four-by-four to go fifteen minutes up the side of a mountain. This whole while, I’m saying, ‘We can’t afford to get a crew up here,’ knowing you’d never pick a location like this in the States. But I’m told, ‘Of course we can,’ and Chris just keeps smiling. I wonder how much of my prep is being eaten up by this madness, but then we got to the top – and there’s this incredible vista, and it is immediately clear that this is worth all that time and effort.”

When Slovis learned he had six weeks of prep for his two episodes, his first thought concerned what he would do with “all those weeks,” but he soon discovered otherwise. “I worked seven days a week getting ready and could still have used another week,” he laughs. “Some of that was due to this being my first show, so I had to learn the culture of this production and how it works, but you are just so involved with all departments due to the lead time to come up with what will be needed in advance of the day. You can’t just run to Macy’s to get a new costume.”

During his work as cinematographer (most notably on the Emmy-winning Breaking Bad) and as director, Slovis has always preferred shot lists to storyboards. “Boards don’t always translate to the real world in terms of framing,” he maintains. “But this series relies heavily on storyboards and photoboards.” The latter arise out of location trips during prep, when the director photographs stand-ins in a variety of potential shooting environments. “This step is essential in letting us determine if the locale can be dressed out – which is the preferred option – or if we’ll have to cover aspects of the frame with VFX.”

With six episodes under his belt, cinematographer Robert McLachlan, ASC, CSC, reports that GOT’s major VFX sequences are addressed early in each season’s prep.

“The climactic stuff for the last two episodes of Season Five, which we shot during October, was the subject of meetings in L.A. with director David Nutter back in April,” McLachlan recalls. “Boarding and extensive previsualization began, including techvis, so that each department would have no surprises down the line, and planning for VFX design could begin.”

Lead visual effects supervisor Joe Bauer and lead visual effects producer Steve Kullback are heavily involved up front. “We start by putting our heads together with the others to make guesses about who will be doing what based on the script,” explains Bauer. “From there it’s a matter of figuring out hand-offs between departments. There’s a film language with live action from which you don’t want to depart when entering the realm of VFX, so it is rare that we do a full CG shot; realism benefits when at least some elements from all departments are included. Even on our standalones, we’ll rely on reference from set and from stunt performers to keep working from some real-world aspect.”

Another real-world concern is dealing with the physical realities of locations and their impact on production. “When doing previs for our dragons and giants,” says Bauer, “we put the digital camera on the digital crane or dolly so that our virtual world matches the conditions Production faces with their equipment. By staying in the world of real photography, we can generate info and give that tech back to production so they know how much track will be needed and just how far the crane is going to have to extend, which makes the shooting much more efficient.”

McLachlan stresses the “director as filmmaker” angle as key to making the show work. “A lot of DGA members shoot everything from every angle, which most producers like, since they can do whatever they want in post,” the cinematographer observes. “But that kind of piecemeal shooting isn’t cinematic. Here, you have to be more selective up front, and so the show employs directors who have a vision going in.”

Game of Thrones has shot on ALEXA from the beginning, and has been captured via Codex starting in Season Two. Only plate shoots and shots requiring exceptional amounts of post work are acquired in RAW, though one unit now carries a 4:3 camera to facilitate the effects effort. McLachlan credits both Newman and executive producer Bernadette Caulfield with coordinating the huge logistical monster that is production.

“They’re juggling ten episodes that shoot with two units,” he marvels. “As a result, I may shoot three or four days with one unit, then do a day of prelighting and rehearsal while working with a different crew. You hopscotch around, sometimes squeezing in a day or two in Croatia before flying back to Belfast.”

Since episodes often rely on oft-used sets and locales, continuity of look is a factor. “When DPs start on a new season, they get an iPad with what is called a flipbook,” McLachlan reports. “It includes frame grabs from the most successful examples of how each set has been photographed, with chapters showing how various DPs handled locations each season, and how it all looked after final color timing – there’s some variance, since there’s more than one cook in the kitchen.”

With eight episodes to her credit, cinematographer Anette Haellmigk reigns as the queen of Thrones shooters, earning one Emmy and two ASC nominations in the process. Haellmigk often finds it necessary to eliminate light from above or the side of frame while on location.

“I’m always using eight-by-eights or twelve-by-twelves on closer shots,” she reveals, “and when we shoot Harrenhal [Castle] in Northern Ireland, I’ll use flyswatters. With really sunny conditions, I may use a 40-by-40 overhead to control the light intensity. Production says, ‘Shoot in all weather,’ so matching is an issue. I recall one scene in a quarry over several days requiring dark overcast weather. Since we were shooting in November, the sun came into the set for a few hours; we had to block it. We built a huge wall of negative fill with 20-by-40s suspended horizontally from three or four Condors.”

McLachlan has faced similar conditions. “I had a 20-by-20 solid on a Manitou that let me get some modeling on faces,” he reports. “That only took five minutes, but it turned out we needed to be doing thirty setups per day. Five times thirty cuts a big hunk out of your shooting day, so I just had to stick that away in the corner and do without.” On one grueling stretch this season, McLachlan had four ALEXAs turning almost continuously in order to record 127 setups in 9.5 hours. “Our playbook was the size of a small phonebook,” he chuckles, “but it let us know all we needed to do and at what time of day it needed to be shot.”

Earlier in her career, Haellmigk worked on Paul Verhoeven’s VFX blockbusters Total Recall and Starship Troopers. She finds that the evolution in digital effects has streamlined some of what was once tedious and time-consuming.

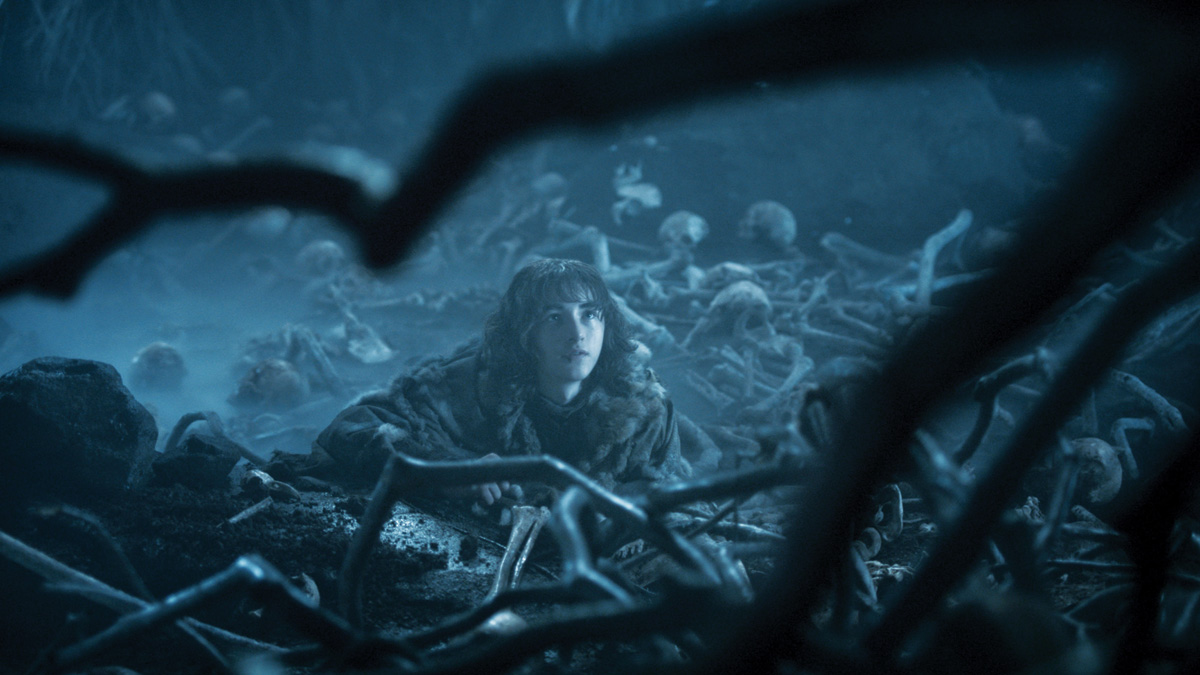

“We often need only small screens for composite work, and sometimes can do without them altogether,” the German-born Haellmigk offers. “We had a very big fight scene in season four with several ‘wights’ – our reanimated skeletons – and putting green screens up behind the performers for every shot would have been very impractical.

“So we ended up only using it for one shot, and VFX was able to make the rest of the sequence work just by employing the empty passes shot after the talent, along with their terrain measurements and markers.”

Scanline VFX was tasked with realizing the battle of the wights, translating the action of the stunt personnel, who wore prosthetics over green costumes that facilitated extraction.

Haellmigk characterizes Season Five as being “more of everything” – more VFX, more dragons, and even more challenging. “In the past, I just had some minor dragon scenes when they get locked up,” she recalls, “which involved shooting a green screen dummy head so the actress could appear to put restraints on.”

With the dragons getting larger and more active, it can only mean fire-breathing attacks are on the way. And, Bauer says, there always issues with CG fire. “If you can’t spend time to refine it to work with a specific environment, it will look wrong,” he insists. “This happens even on high-ticket features.

“Since fire is an object that throws shadows, with an appearance that is affected by the sun and other strong sources, we always try to photograph real fire on location,” Bauer continues. “If you just rely on generic fire elements shot against black, that can work for a cave shot but will fail when comped into a daylight plate.”

During Season Four, the physical effects crew piped the grounds being strafed with flames, with the idea that only the fire coming from the dragon’s mouth would have to be comped. Unfortunately, strong winds flattened the practical fire, requiring post enhancement that Bauer acknowledges as a less-than-ideal solution. To accommodate the expanded dragon workload, Rhythm & Hues joined this season’s VFX roster, augmenting Pixomondo’s work on the flying lizards.

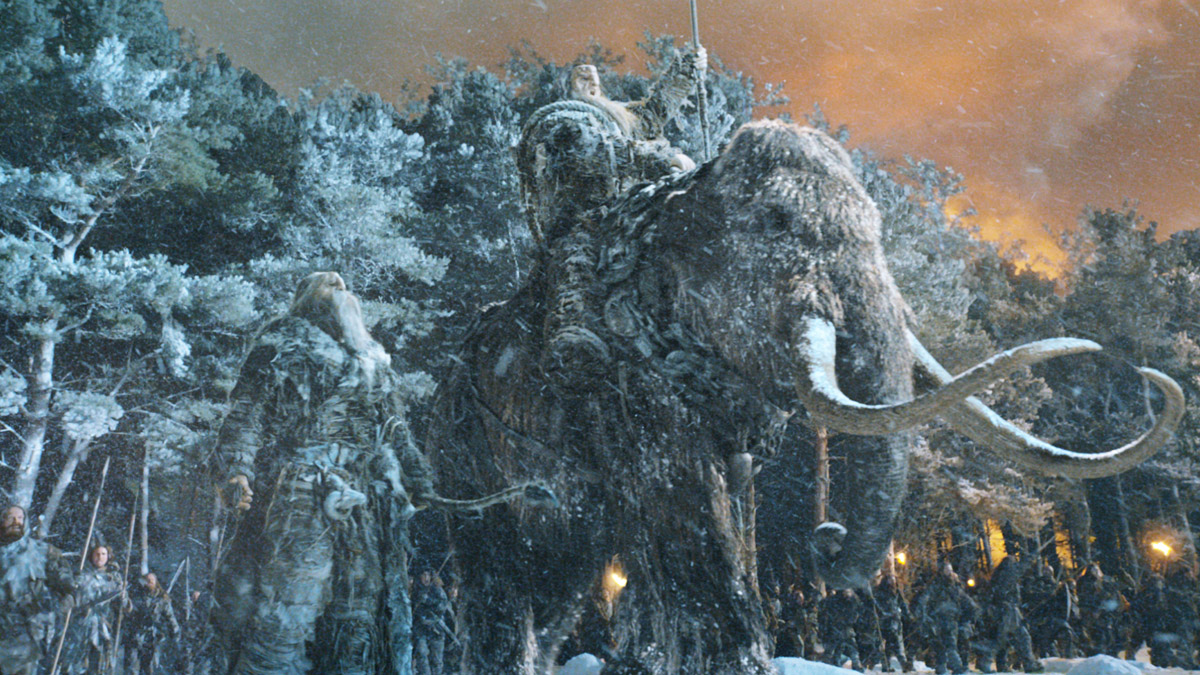

A major sequence in Season Four – realized by MPC – involved giants alongside human-sized wildlings and woolly mammoths, all approaching a great ice wall.

“In previs done at The Third Floor, we made a point of keeping the camera at human eye height,” says Bauer, “to get across the true size and menace of the giants. We cast much larger performers, too, because when a normal-sized person acts big, you can tell he is exaggerating his movements. Big people have that gait naturally, so all you have to do is slow the film down to get them the rest of the way to standing a convincing 12 feet tall.” Camera moves were scaled appropriately to allow proper integration of the other characters, and shots featuring attackers climbing the wall re-employed a foam wall section built for Season Three, augmented by a CGI set extension.

An L-shaped 30-foot-high by 400-foot-long green screen was deployed for the Northern Ireland location work in the giant sequence. “We put red flashing lights on top,” Bauer adds, “both for tracking and so low-flying planes wouldn’t hit it.” The series experienced a mishap during shooting in Spain, when a huge screen was ripped apart by winds. “This year production committed to inflatable green screens for our last stretch of work,” notes Bauer. “Normally we finish by mid-November, but we were going well into December this time, when the worst weather the British Isles can throw at you arrives.

“To avoid a possible repeat of Spain, they ordered them, and the inflatable greens were rock-solid, even in the heaviest winds,” he continues. “That’s a great innovation. So many things continue to improve. We can deal with filtration in front of the lens now, since the cameras are so good our key edges don’t get screwed up. And between the Arri equipment for metadata capture and all data wrangling and HDRI passes, we’re never short of information for the vendors.”

Earlier this year a preview of Season Five was screened in IMAX theaters, along with the two-part conclusion to Season Four. While Bauer admits to some trepidation (“I signed off on shots viewed on a 60-inch monitor, not a 60-foot screen!”), McLachlan has cause for more optimism. “At IBC [the International Broadcasting Convention held each September in Amsterdam], Arri up-rezzed some of my footage to 4K and projected it on a 65-foot screen,” he notes. “While prepared for the worst, I wound up being blown away by how well the material held up.”

Ensuring her material looks its best is why Haellmigk makes a point of trying to get as close to a final look as possible on the day, which facilitates the DI. “Initially, post had requested I shoot one stop overexposed, especially on exteriors,” she recalls. “There was some dialog about that … until the finals colorist explained that more time would have to be spent on an exploration in the DI if the image wasn’t nailed up front. So my approach – baking-in lighting, contrast and color temperature, which I change in the camera – gives the colorist a clear idea of intent. Also, I’ve always been available to do the final grading, so I’ve been lucky in that regard.”

Perhaps Michael Slovis has the track on why this series succeeds consistently in ducking the curse of many a genre entry, when the VFX tail wags the dog. “VFX meetings never get off track, because these guys aren’t pitching, ‘I’ve got a kick-ass effect to throw in,’” Slovis observes. “For Joe and Steve, it is about delivering the story beats; their huge team always keeps that front and center. The quality of the work goes far beyond what I even hope for, but it’s a never-ending dance between production and effects to deliver a thousand shots in nine months, and it’s not a task I’d advise mere mortals to tackle.”

by Kevin H. Martin / photos courtesy of HBO