Circus ringleader Rodrigo Prieto, ASC, AMC, leads a talented Guild crew in visualizing the best-selling novel, Water for Elephants, for the big screen

Sara Gruen’s novel, Water for Elephants, became a huge bestseller by blending rich period details and a sweeping romance with a deep understanding of the relationship between man and animals. Its popular success made it an obvious studio fast-track, though the director tasked with the book-to-screen adaptation was an unusual choice. Austrian-born helmer Francis Lawrence is a one-time 2nd AC, who studied film at Loyola Marymount University and made a splash in the world of music videos, developing a signature style with artists from Aerosmith to Shakira. Six short years ago, Lawrence made the jump to features with Constantine, followed soon after by the visual feast that was I Am Legend (shot by Andrew Lesnie, ACS, ACS). It was no surprise then that when Lawrence went about assembling a creative team to help bring the Benzini Brothers Circus to life, circa 1930s Depression-era America, he started with acclaimed cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto, ASC, AMC.

Known primarily for his work with Alejandro González Iñárritu (Amores Perros, 21 Grams, Babel, Biutiful) and Oliver Stone (Comandante, Alexander, Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps), Prieto has also lensed projects as diverse as Frida, 8 Mile, and 25th Hour. In 2007, he earned a well-deserved Oscar nod for the wonderfully textural, emotional landscapes of Brokeback Mountain.

“Francis told me that he felt that there was an intimacy in the films I’ve worked on,” Prieto recounts. “He felt there was a connection between the performances, camera work and story that I could bring to Water for Elephants. In preproduction, when we were shot-listing, all of our decisions were based on, ‘How do we get into the character’s minds and follow their emotional arcs through camera lighting and composition?’”

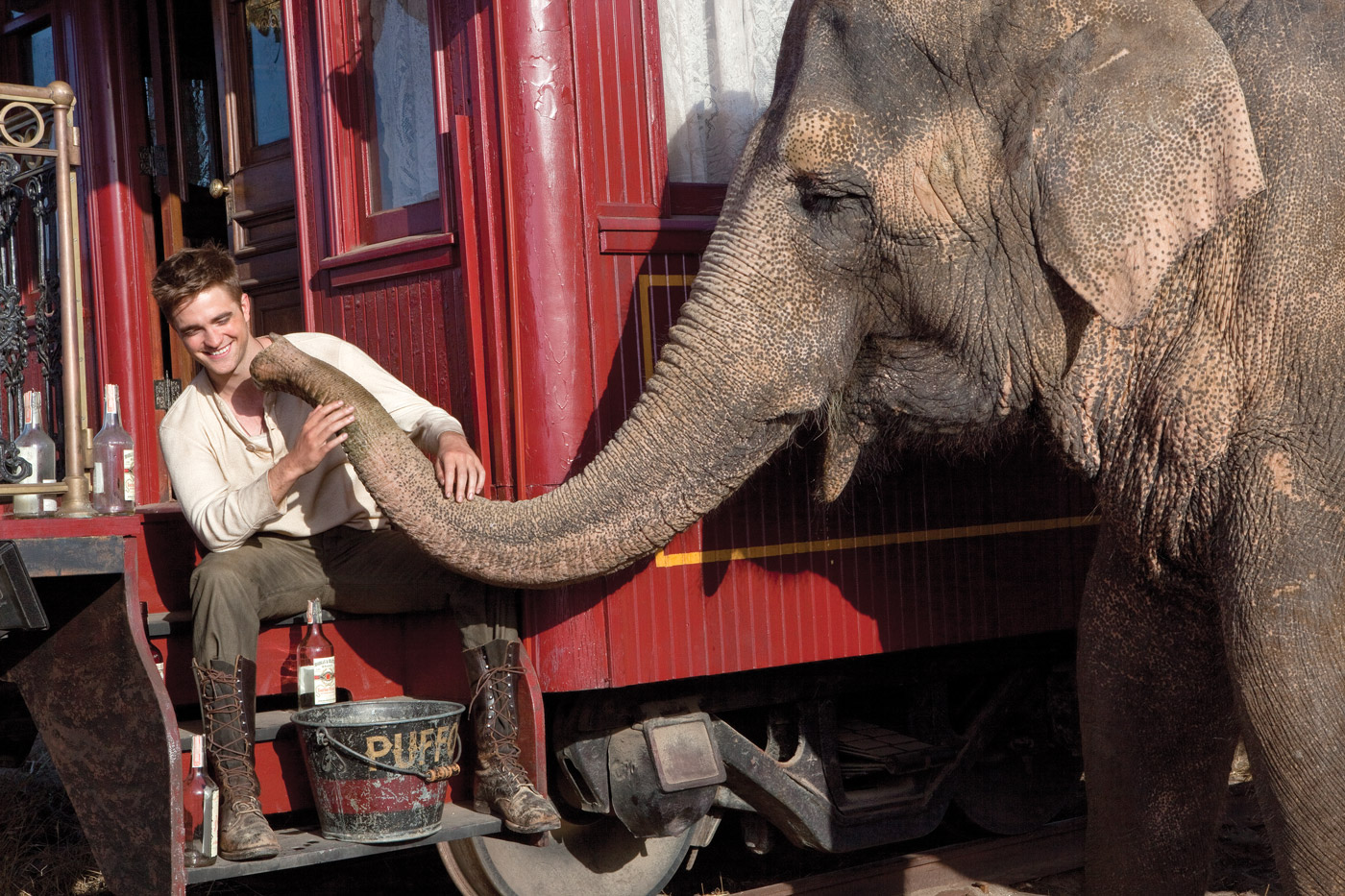

Water for Elephants traces the adventures of Jacob Jankowski (Robert Pattinson), who is forced to drop out of Cornell Veterinary School, and is left penniless during the Great Depression after his parents are killed. Stumbling upon a travelling circus, Jankowski lands a job caring for the exotic menagerie, most importantly a high-strung performing elephant named Rosie. He also falls in love with the big top’s equestrian trainer and rider, the glamorous Marlena (Reese Witherspoon), who is married to the cruel ringmaster August (Christoph Waltz).

Given the precise period theme, the film’s 50-day schedule and a budget more suited to a romantic comedy were supremely ambitious. In fact, one of the keys to staying on track was Prieto’s extensive preparation with Lawrence. From their discussions, the cinematographer compiled a 52-page photographic breakdown of each scene, right on down to specific lenses and equipment that was required.

“I started providing a detailed photographic breakdown on Brokeback Mountain with Ang Lee,” Prieto explains. “[Lee] had asked me to do a scene-by-scene breakdown of the camera moves and type of lights. But I took it even further, adding special equipment and information on what my intentions were for each scene, both theoretically, like the mood, but also technically, for any special lenses I would need and film stocks I would use. [The breakdown] became a way for me to make sure my crew was always aware of what I was trying to do for each scene.”

Second Unit director of photography and C-camera operator Robby Baumgartner has worked with Prieto since 2000, primarily as a gaffer. “Rodrigo starts where most people would be, at the end of the film, if they were to write a synopsis of what they did,” he explains. “It’s great for me, because you can take what he has, and, with your own knowledge, improve on it. You’re not figuring it all out on the day [of filming].”

Production designer Jack Fisk agrees, noting that Prieto is the first cameraman who ever handed him fifty pages of notes. “I said, ‘Rodrigo, there’s no way I have the time to read this,’” Fisk laughs. “But I’ve never seen a contemporary photographer work so fast. Rodrigo was always so excited, saying, ‘I’m making an old Hollywood movie.’ And Francis has got such a keen visual eye, he knows exactly what he wants and I never saw him get rattled.” Key grip Joseph Dianda continues the praise, adding that, “[Lawrence] is never bothered by anything. He takes it all in and gives it all back. Even if a PA came up to him, he’d smile and listen like he was speaking to another director.”

Lawrence briefly considered utilizing digital capture, but because of the era and style of the film he had in mind, Prieto selected Panavision® Millennium XLs outfitted with the G series anamorphic lenses. Kodak’s Vision 3 5207 and 5219 were the stocks of choice. But as Prieto notes: “We used the Fuji 500T Eterna Vivid [500 ASA] when Jacob first sees the circus, sneaking in through the flaps of the tent, because we wanted that to have richer color saturation and much stronger contrast. There’s also a montage where things are going good and the elephant is performing well and we used the Vivid there as well,” he adds. “Then there are some moments where the elephant is not behaving and things are not going well, so for that we used the 5207.”

From the standpoint of design, Fisk says building a 1930s circus for Prieto’s camera was an outright joy. “We had trapeze artists and clowns, and could have opened for business,” Fisk jokes. “We built the tents ourselves and then got in touch with the people at L.A. Circus. [Co-founder] Chester (Cable) is nearly 80 years old and he’s the only guy we could find who even knew how to put up one of these old circus tents. He began in the circus in the 1940s and became our number-one resource for how to do things.”

Because contemporary circus tents are different than those of eight decades past, Fisk had two period canvas tents built, then supplemented with smaller tents from L.A. Circus’ owners Cable and Wini McKay. The company has also provided period sets for HBO’s Carnivale and a Christina Aguilera music video, with funds going to give free classes for children around the world interested in learning about the circus arts.

While Prieto’s past films have often featured complex hand-held shots, here he opted for a more traditional style – 35-foot Technocranes and dollies – to echo the simplicity of the film’s period. He also used an 85-foot Akela crane to capture a shot looking down as the center pole of the big circus tent is raised, as well as other sweeping shots of the circus writ large.

This old-school approach was mostly applied to the lighting, although small LED units were hidden inside oil lamps by gaffer Randy Woodside, to give the filmmakers more control. As for controlling the sun, that became doable after Dianda and his rigging key grip, Chris Leidholdt, made 30-by-30s on Pettibone forklifts that could move quickly and efficiently to whatever position Prieto needed.

“Sometimes we’d use the sun and half soft frost,” says Dianda. “When we wanted to block the sun we would put full grid on it. Then when we got into night, we’d turn the 30-by-30s into ultra bounces and create a huge area of daylight. It was my first time using this and we really put it to the test.”

Anyone who’s read Gruen’s literary tapestry will recognize its true star, Rosie the elephant, here portrayed on-screen by Tai, whose debut came on Operation Dumbo Drop. First AC Bob Hall is only half-kidding when he says that, “There are a lot of actors who could take lessons from Tai.” Hall calls the pachyderm “incredibly intuitive,” citing a scene shot inside a location boxcar that featured two cameras and a dolly that Tai had to avoid as she laid down. “The trainer is going, ‘Careful, Tai, watch your foot,’” Hall recalls, “and you could see Tai gingerly keep her foot back so it didn’t touch the camera!”

Shooting a POV from Tai’s back was another matter. “We’d been watching Reese ride around effortlessly on Tai for a long time, doing handstands and dismounts that involved sliding down the trunk,” Steadicam operator Brooks Robinson, SOC, explains. “So sitting on the elephant’s back appeared fairly straight-forward.”

But when Prieto got on top of the elephant with his still camera, he says, “Maintaining [my] balance was very tricky. Even with my little still camera I thought I was going to fall forward!” So Prieto ordered up an Easyrig, a support vest with a cable that attaches to the handle from above, moving the majority of the weight from the forearms onto the hips.

“I was up on Tai for 20 or 30 minutes with the Panavision XL on my shoulder, looking straight down the entire time,” Robinson remembers. “This would have been physically daunting in traditional hand-held mode, but the Easyrig took the weight off of my arms and made the shot doable. Gary Johnson [Tai’s trainer] assured me I was fine, and he grabbed onto my foot as we walked along during the shot for support. By the time B-dolly grip Kenny Davis and I came down, my legs had started trembling from holding on so tightly with my knees – they hurt for the rest of the day!”

Hall describes one of the film’s most challenging shots as a Steadicam move through three period Pullman train cars, with a 180-degree turn for a dialogue halfway in. “We had dozens of extras to make our way through and two 1st ACs, myself and B-camera AC Clyde Bryan, trading off pulling focus on a Preston FIZ remote,” Hall explains. “During the 180-degree turn, the camera was facing the assistant, so he had to stay hidden in the turnaround area while the operator went another 1-1/2 car lengths to finish the shot. We decided that we would have to hand off focus remotely. Clyde Bryan did the first half. He used an Iris handset that can be switched to the focus channel. I had the main handset with me. When the Iris handset is switched to focus, my handset is disabled. There is a 1-second delay during the switch.”

The two ACs saw a point where Bryan could still see the camera and actor as well as a one second window where the focus would remain constant. “I had a Panatape® readout on my handset and I was wearing a headset so that I could hear dialog,” Hall continues. “At the point that Clyde was losing sight we used a dialog line cue and he switched his handset off. That now gave me control. I had to keep my focus dial close to his before the switch to prevent a jump when control went to me. I used my Panatape readout to do that. Moments after the switch, I could see them coming down the hallway with the camera now pointed away from me. At the end, I had to duck to allow another 180° turn for the last dialog of the scene as they went into a fourth train car.”

At press time, Prieto was overseeing the DI at EFILM with colorist Yvan Lucas. And while it’s still in the initial phase, Prieto says the trickiest part will be matching some of the special effects and day-for-night shooting.

“We begin the movie with a fairly long sequence where Jacob is in the forest resting his feet in a creek with fireflies in the air,” he explains. “He sees the flickering light of a train through the trees, runs toward it and decides to jump on the train.

“At the actual location, there was no place to put big cranes for lighting, so I decided to go day-for-night. I wanted to hide the fact that it was day-for-night, so in the forest I lit him fairly close with a big Arrimax 18K HMI with full grid cloth. You feel like the light on his face was either moonlight or actually lit by us. I underexposed by one stop because I preferred to darken it further in the DI.”

Prieto says the actual train “headlight” for the first shot of the scene was a 24K tungsten on a hyrailer (a converted pickup truck on tracks) shining straight into the lens. “We had to find units that would overpower the ambient daylight and be really bright,” he continues. “For another angle, we shot two plates: one of Jacob moving up to the train in daylight and another plate at night from exactly the same angle of the train moving towards the camera with its headlight on, which we had replaced with a 2K blonde. The 2K blonde on the front of the train flared the lens on the night pass and lit the track and rocks around it. Visual effects mixed the day-for-night shot with the nighttime plate of the train. It was quite effective and looks like we did shoot the scene at night.”

Towards the end of the show, Prieto also used some antique technology to create period newsreel footage – a hand-cranked ARRI 2C camera with spherical lenses and a 3-by-4 aspect ratio. That footage was later aged in post to complete the appearance of a documentary film of the era.

“Hand-cranking was fun,” Prieto beams. “Lisa Guerriero, the 2nd AC on these shots, was trying to find a rhythm that approached 20 fps. It wasn’t easy at all, and it gives you a respect for those old cameramen. Maybe you can simulate this in postproduction, but it would never have the organic feel of an actual hand-cranked camera. We were going backwards from new technology to uncover these older techniques. That was part of the great fun of this movie.”

By Ted Elrick / photos by David James