Gordon Willis, ASC (1931-2014). By Pauline Rogers.

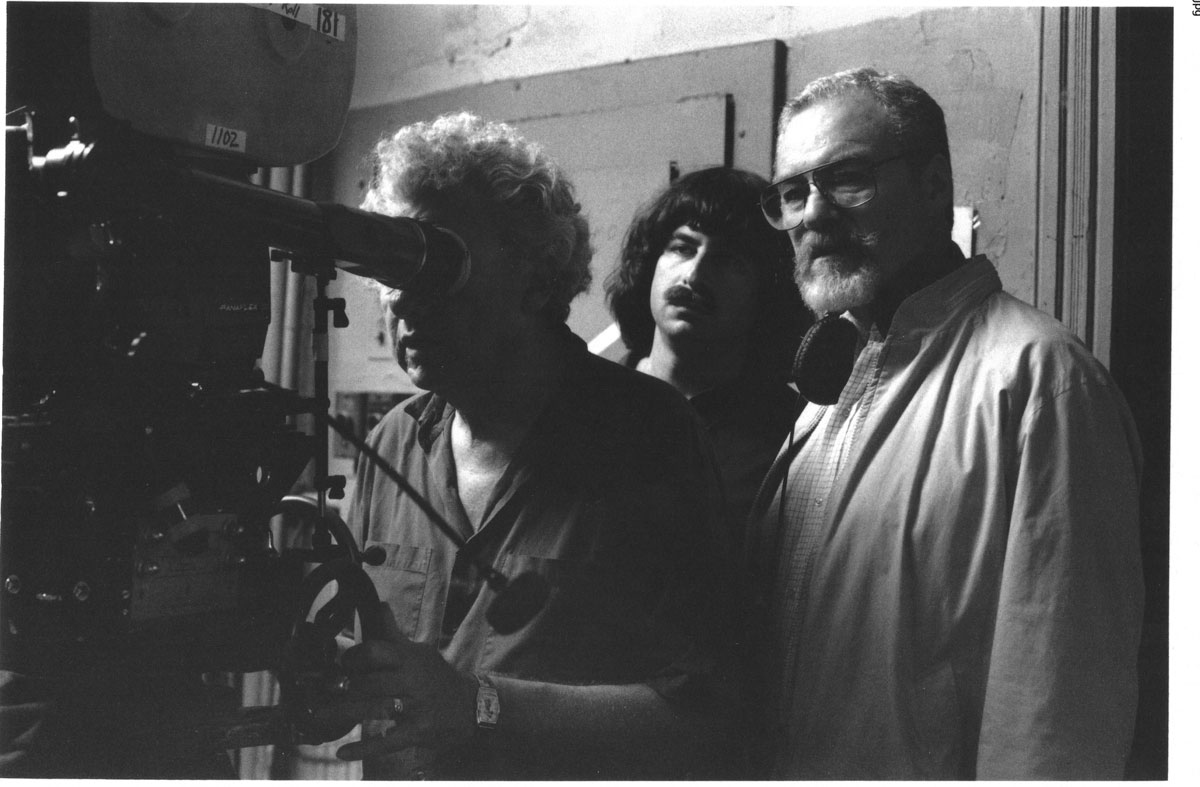

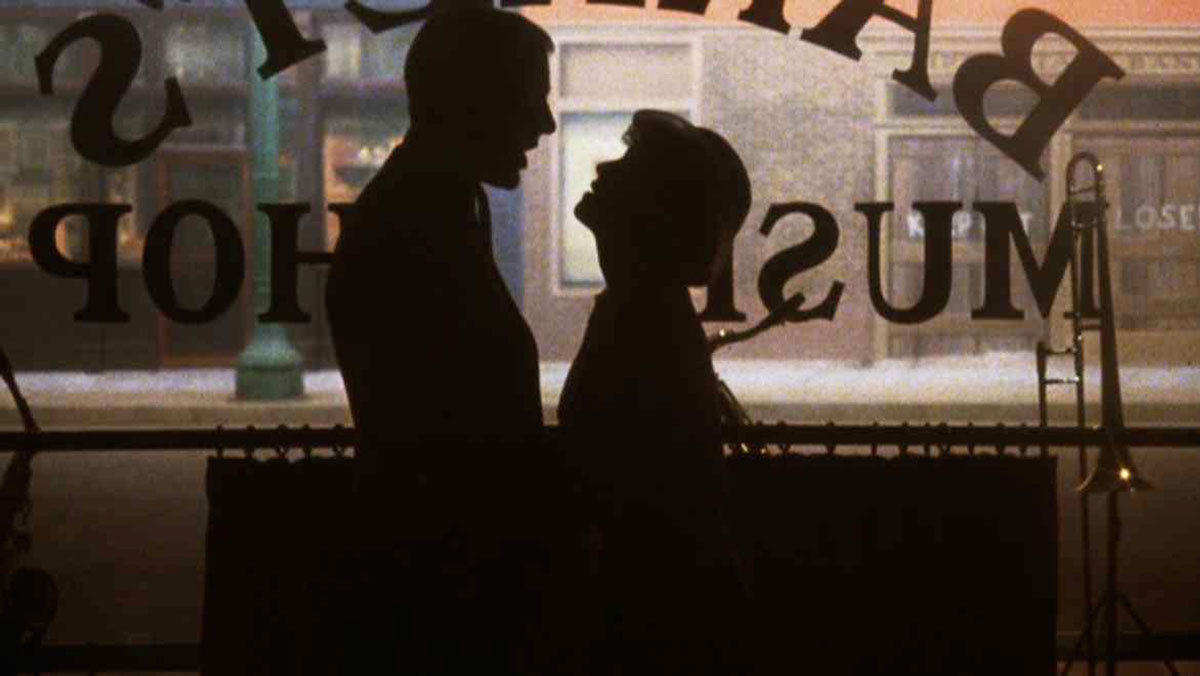

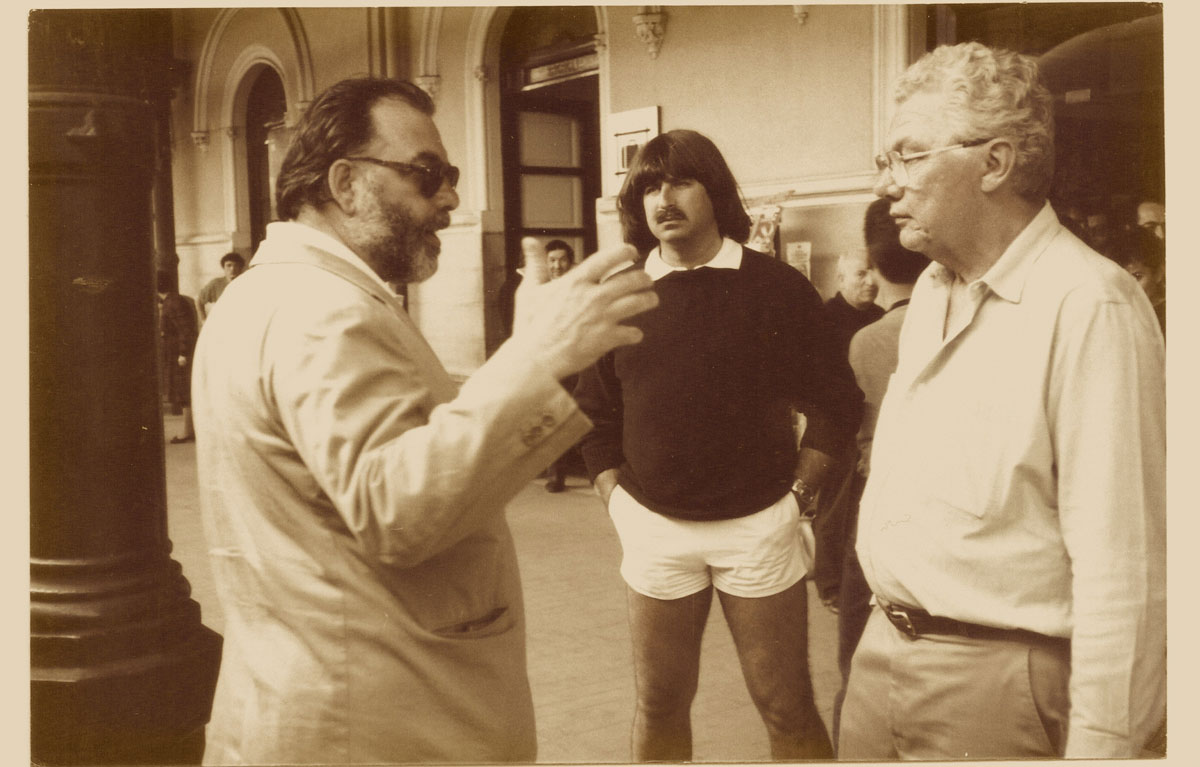

Zelig (1983) Photo by Kerry Hayes

Zelig (1983) Photo by Kerry Hayes

As soon as word got out that Gordon Willis, ASC often referred to as “the Prince of Darkness,” (more on that nickname later) had passed, tributes began popping up in many industry (and non-industry) platforms, much of the material garnered from a long-form press release/obituary compiled by Stephen Pizzello, Editor-in-Chief and Publisher, American Cinematographer and author of a soon-to-be-released book on Willis.

Certainly, the list of “Gordy’s” accomplishments were unparalleled: Francis Ford Coppola’s epic Godfather movies; the Woody Allen comedies – Annie Hall, Manhattan, Zelig, Broadway Danny Rose and The Purple Rose of Cairo. There were the iconic 1970’s era dramas with director Alan Pakula – Klute, The Parallax View and All the President’s Men – and everything else in between, from James Bridges’ The Paper Chase and Bright Lights, Big City to Herb Ross’ Pennies From Heaven.

Twice nominated by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences (for Zelig and The Godfather Part III), Willis was given a special Oscar in 2009. He was also nominated for the British Academy Award for All the President’s Men, Manhattan and Zelig. And there were other honors – two National Society of Film Critics Awards, a New York Film Critics Circle Award, a Boston Society of Film Critics Award, and the ASC Lifetime Achievement Award in 1995.

Pizello’s obit, and others like them, made clear that Hollywood (and film fans around the world) recognized the talent and artistry of Gordon Willis. But to really get inside this legend’s creative mind, we wanted to hear from his working mates, those filmmakers who were “in the trenches” with the man that ASC President Richard Crudo said: “changed the way movies looked and changed the way we look at movies.”

Bits and Pieces

It was Conrad Hall, ASC, who first coined the moniker “The Prince of Darkness,” after seeing the first shot of Marlon Brando in The Godfather with absolutely no light in the actor’s eyes. According to Michael Chapman, ASC (then operator) Gordon’s idea was “you couldn’t see his eyes but afterwards with light you could see his soul.”

To perhaps his most legendary collaborator, Woody Allen, explaining why he takes so long to prep a set, Willis once remarked: “We’ve already made this movie in our heads. This is the easy part. We’re just recording it.”

Willis turned down Apocalypse Now, figuring if he had to be locked in the jungle with Francis Coppola for six months, “only one of them would come out alive.”

When asked by Doug Hart what a camera crew should never do if they want to keep working for Gordon Willis, the DP remarked: “Operators are always on the phone looking for their next job. Firsts are always playing with the wheels because they want to become operators. Seconds are chatting with extras, trying to get laid!”

Those close to Willis recall how he ran the quietest of sets with a military precision, often communicating with gestures and glances, rather than words. Craig DiBona remembers how Willis never talked when he was lighting. “He’d walk into a set with his meter, hold up his fist for a focal point of the lighting, then use his fingers to indicate changes.

David Knox remembers that he would often pull out his own personal can of dulling spray [to the chagrin of stand-by scenic artists] to knock down reflective overexposed highlights.”

Willis, who used the same SP series of lenses – worth about $100 – for most of his career because they gave him the look he wanted, had a phobia about going over bridges. Often a challenge considering Woody Allen wouldn’t go through tunnels!

Who’s Really in Charge Here?

Recollections from Producers, Directors, and Editors

Francis Ford Coppola’s favorite description of Willis was that, “he ice-skated on the film emulsion.” Coppola recounts his favorite Gordon Willis story:

“We were with Dean Tavoularis and Gordon, I think at Dean’s home. We were going to watch a baseball game, and were gathered around the television with drinks and snacks. But Gordon kept getting up and adjusting the color on the set. When he was finally done, and went back to his seat so we could all watch the TV, the screen was almost black, so all we could see were a few highlights of the players.”

Woody Allen, whose first experience with Willis was on Annie Hall, remembers how “Gordy introduced me to a concept that I always call ‘comedy in the dark.’ I remember saying to him in a scene, ‘I’ve got a great joke here but the way you’ve lit it no one can see me.’ And Gordy said, ‘that’s okay, they can hear you!’ and I said, ‘What are we shooting here, a radio show?’ He said, ‘trust me.’ And we did it his way and it looked very pretty and I got my laugh.”

Producer Robert Greenhut recalls how they had the technology on Annie Hall to do split screen. “But to avoid loss of generation [Gordy’s obsession – he would have done individual prints off the original negative if he could], we did the split screen like kids do,” Greenhut shares. “We had Diane Keaton watching herself in half the scene with Diane in one configuration, the split screen in another configuration. Gordy put a matte in front of the camera for half the screen and shot half of her on the other side, rewound the magazine backwards and moved the matte to the right side of the matte box, put Diane in the other configuration, and she made believe she was watching herself. Then we shot again.”

Producer Michael Peyser, who worked as a UPM on Manhattan, recounts a similar example of Willis’s sublime use of craft. “I remember filming in the Public Theater and seeing a news item that Chrysler was sponsoring a well-known Italian fireworks display that evening in Central Park,” Peyser begins. “So I asked Gordy and Bobby Greenhut if I should try to find a proper vantage to shoot some fireworks over the skyline for our collection of montage imagery. A brief chat with Gordy determined that the best vantage point would be from 81st and Central Park West – a building called the Beresford.

“David Brown and his wife Helen Gurley Brown lived in a top apartment. I tried to reach them, but they were traveling. Alan Funt of Candid Camera, for whom Woody had worked during his writer/comic days, lived in the next apartment on top facing south. His apparent lack of affection for his former minion provided a firm ‘no way.’

“The next apartment from the corner on the top belonged to the family of my location assistant and buddy Ezra Swerdlow. Gordy and I agreed that, because we could get permission from them, but not the snooty co-op board, we should smuggle the camera up into the apartment as some kind of expected delivery. Gordy then found the perfect place to shoot out of the eastern-most south-facing window – their bathtub! He always knew just the right place to put the camera, Peyser laughs.”

Editor Michael Miller remembers how easily Willis could finesse emulsions. “In addition to all the things that are common knowledge about Gordon Willis, he was also a brilliant lab chemist. The warm tones of The Godfather trilogy, the brilliant yellows of Midsummer Night’s Sex Comedy, and the perfect, stark contrast of Manhattan were all achieved through choosing the perfect printing lights [rather than filters]. And his perfectionism could make actual lab technicians crazy.

“I was privileged to work with Gordy as the assistant editor on Manhattan, an incredibly tough job for lab man Otto Paoloni at New York Technicolor,” Miller continues. “Otto had been Gordy’s lab guy on Klute, Annie Hall and The Godfather, among other pictures, and wanted everything to be perfect on Manhattan. But that wasn’t easy, considering that New York Technicolor was no longer processing black and white negative. That meant Otto had to be responsible for the work of another lab, Guffanti, a low-end plant west of Technicolor in the Times Square area.

“[Otto] would wait every afternoon for the developed negative to arrive so he could make the prints to Gordy’s specifications. And I would wait with him so I could race back to my cutting room with the still wet dailies to sync them for the screening a few hours later. If wound too fast [at the speed at which color negative is wound], the negative would pick up a static charge that would appear on the print as white branches or white bars, ruining whole takes.

“Otto was quite chagrined when he heard that his favorite cinematographer would be shooting the next Woody Allen film, Stardust Memories, also in black and white,” Miller adds. “‘Mikey,’ he asked me, ‘why’s Gordy have to do another picture in black and white?’ ‘Well, Otto,’ I replied, ‘people thought it took a lot of balls to shoot Manhattan in black and white. They’ll think it really takes balls to shoot a second one that way.’ ‘Mikey!’ said Otto. “What’s Gordon Willis need with four balls?’”

Through A Lens Darkly – Memories from the Camera Department

Michael Chapman, ASC, and Tibor Sands were a new operator and assistant, respectively, on The Godfather, and a key sequence where Talia Shire’s character descends a long staircase (and doesn’t always hit her mark). Following her in close-up was difficult, and tensions began to escalate. “Coppola wants the shot and Gordon stands firm – she has to hit her light,” Chapman recounts. “I took a look at the two of them and knew Gordon wasn’t going to give in. In a few moments, he’d just walk off the set.

“Suddenly, I decided I needed to make a trip to the men’s room. And I stayed there – until Francis and Gordon had come to terms. If I’d stayed and Gordon had left, Francis would have turned to me and said, ‘you shoot it.’ My walking away didn’t make Francis happy – but then again, I spent many more years working with Gordon Willis.”

Sands remembers Willis’s total control of the set. “In the first Godfather – the wedding procession comes down to the café and passes a stone fence. It was very low on the right and rigged so that when the procession goes by it would explode with little fireworks. Gordy wanted to see what it looked like. Production objected. It would take a whole day to reset. ‘I want to see the effect,’ Gordy kept saying. He won. They showed him the effect. And it was a good thing – because it was rigged badly, and the fireworks would have injured the actors. He practically saved their lives.”

Craig Di Bona recounts how shooting in Italy for Godfather III was fraught with challenges. “I remember the first time Diane Keaton walks into Corleone’s office. There was a long discussion. ‘Keep your distance. You fear this man.’ Gordy lit so she’s about 25 feet from Pacino, and there is only a little piece of him in the shot. They roll. Her character gets angry. She walks across the floor and right up in Pacino’s face. They cut. She immediately turns to Gordy and says she’s sorry and won’t do it again. He looks at her for a moment. ‘Not unless you want to assassinate yourself.’” [She didn’t do it again.]

Doug Hart, who assisted Willis on five Woody Allen movies, relates this tale from Stardust Memories: “We had a complex shot for the big finale – a set built at the studio –that was supposed to be the hotel in the Jersey shore. It was an octagonal lobby with registration in the center. There were several stairs, five doors, and more. Woody wanted to rotate 720 degrees and catch people walking, and action in the background, like the three tap dancing nuns. We would have hundreds of extras, many of the people from earlier in the film, from various locations.

“After we blocked and marked the scene, early on Monday morning, I was standing next to Gordon when Woody came in. ‘When do you think we can shoot?’ Woody asked. Gordon walked into the set, did a 360, looked around and turned to Woody: ‘Thursday.’ Woody turned and said: ‘See you then.’ And he left and came back Wednesday afternoon. It took three days to light and rehearse. We had one take per magazine – about 7 or 8 minutes. No coverage.

“We went to dailies and saw a beautiful shot. After everyone left, Gordon and Woody sat together in deep conversation. Next morning, Gordon came up to me. ‘We’re not going to use that final scene. We decided it doesn’t go with the rest of the movie.’ I could hear production’s reaction. But, they were right. We used another set, one that was already built, and filmed in a movie theater. As people exited the theater, they simply walked in front of the camera with their dialogue and reactions. It worked, even without the tap dancing nuns. Pure Gordy.”

Chaim Kantor recalls being Doug Hart’s 2nd AC on Bright Lights, Big City, working with a different grip/electric crew. “After the actors rehearsed with James Bridges and Gordon, the ‘marking team’ would be brought in to line up all of the shots and mark the actors for the entire scene. The dolly grip would measure the lens height set by Gordon with his finder. Doug would record the focal length of the lens, and I would mark the actors. Once the shot list was established, these setups rarely required any adjustment when actually viewed through the camera. For some reason, as we went from shot to shot on this production, Gordon fussed with the height of the camera, invariably lowering the lens by 2-inches for each setup.

“Years later, working again with Gordon’s regular dolly grip, Ronald Burke, I mentioned the unusual tweaking of the lens height. Burke smiled and explained, ‘Gordon always set the lens 2-inches too high when using his finder. I just subtracted 2-inches from whatever I measured.”

Alan Disler’s memories of Pennies From Heaven involve the first week of shooting. “Gordon had heard that the electricians were getting a lesser rate than they deserved, so after the blocking of a major scene, and setting the shots, and the actors gone to makeup, Gordon placed a chair facing the set and sat there. No lighting. This went on for a half-hour before the UPM had the courage to walk up to Gordon and ask if anything was wrong. Gordon turned to him and said, ‘When the electricians get their f * * * *g money we will start lighting.’ Needless to say, the ‘mistake’ was corrected and lighting commenced.”

That same week Disler approached Willis while he was eating his usual breakfast of egg on plain white bread and milk. He handed Disler a note from the lab that said there was a problem with the camera.

“Immediately, I began thinking about other careers because this one was clearly over,” Disler laughs. When he got the lab on the phone he was told that there were streaks along the side of the frame in the big musical number. “When we viewed the footage, what we saw was Steve Martin dancing towards camera in the big bank set, which had marble columns on the side, and, as the camera dollied back with Steve, the columns filled in the sides of the frame. The streaks the lab reported were the striations in the marble columns,” Disler smiles. “The next thing I heard was the lion roaring. ‘I don’t want to see that &****%^ on this set ever again!’ It was then I picked up the habit of smoking Camels, from Gordon’s pack I had to keep in the front box.”

Randy Nolen, SOC recalls Willis as a man of few words “but I had no problem communicating and understanding what he wanted and expected of me as a [Steadicam] operator [on Malice]. No one stood in front of the camera for no good reason and especially not when Mr. Willis had his eye on the eyepiece. Having non-combatants in front of the lens when the DP is trying to light and block the shot is one of the most frustrating things an operator has to deal with, so I really liked that.

“One moment I will always remember,” Nolen continues, “is an exterior day scene in the morning. When we stepped out of the hotel to get on the crew vans, it was very overcast. [Gordon] looked up at the sky and said we weren’t shooting today. And we didn’t! That really blew me away and I realized Gordon Willis had the respect of the director [Harold Becker] and Production – who trusted the decisions of the Director of Photography. You don’t see that much these days.”

Lights Out

Based on these remembrances, and a body of work that changed the course of cinema history, it’s safe to say we will never see another cinematographer quite like Gordon Willis, ASC. In presenting him with the 2009 Governor’s Award from The Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences, Caleb Deschanel, ASC (the only person who ever talked Gordon Willis into having an apprentice on set) offered one explanation why Willis was never honored with an Oscar.

“The Godfather is considered one of the greatest movies of all time,” Deschanel observed, “and one of the seminal films in cinematography, and yet there was no nomination for cinematography. Everyone knew there’d be a sequel – so maybe they thought – if you don’t get the nomination this time, you’ll be inspired to do even better work on the next Godfather.

“But,” Deschanel added, “There’s an unspoken rule that sequels do not get nominated. Annie Hall: Another unspoken rule: Comedies do not get nominated. All the Presidents Men – this is just my own theory, but maybe it was the wise-ass remarks I warned you about, and word got out. Manhattan: Woody Allen’s love poem to New York, beautiful black and white photography. But, I guess no one told you, the Black and White cinematography award was eliminated in 1967.”

Deschanel continued to say that “there are so many more, but as Gordon would say:

“Let’s go, folks, the earth is rotating.” “Gordon,” Deschanel concluded, “tonight we make right a long standing wrong – not by honoring just one film, but by honoring your entire amazing oeuvre. I know how much you hate fancy words, but tonight is special, and in fact ‘oeuvre’ is just a fancy French word for ‘Dump Truck.’ So, to your extraordinary, and dazzling body of work: we are all so proud to congratulate you for this well deserved honor!”

Sleep well, fair prince. There will never be another like you again.