Directors known for character-driven pictures are rarely hired to steer the venerable James Bond action franchise. With the exceptions of filmmakers like Michael Apted or Lewis Gilbert, the legendary British spy series has relied on former film editors like Peter Hunt, John Glenn, and Roger Spottiswoode, or on veteran action helmers like Terence Young, Guy Hamilton and Martin Campbell to serve up the eye-popping action sequences Bond fanatics have come to expect.

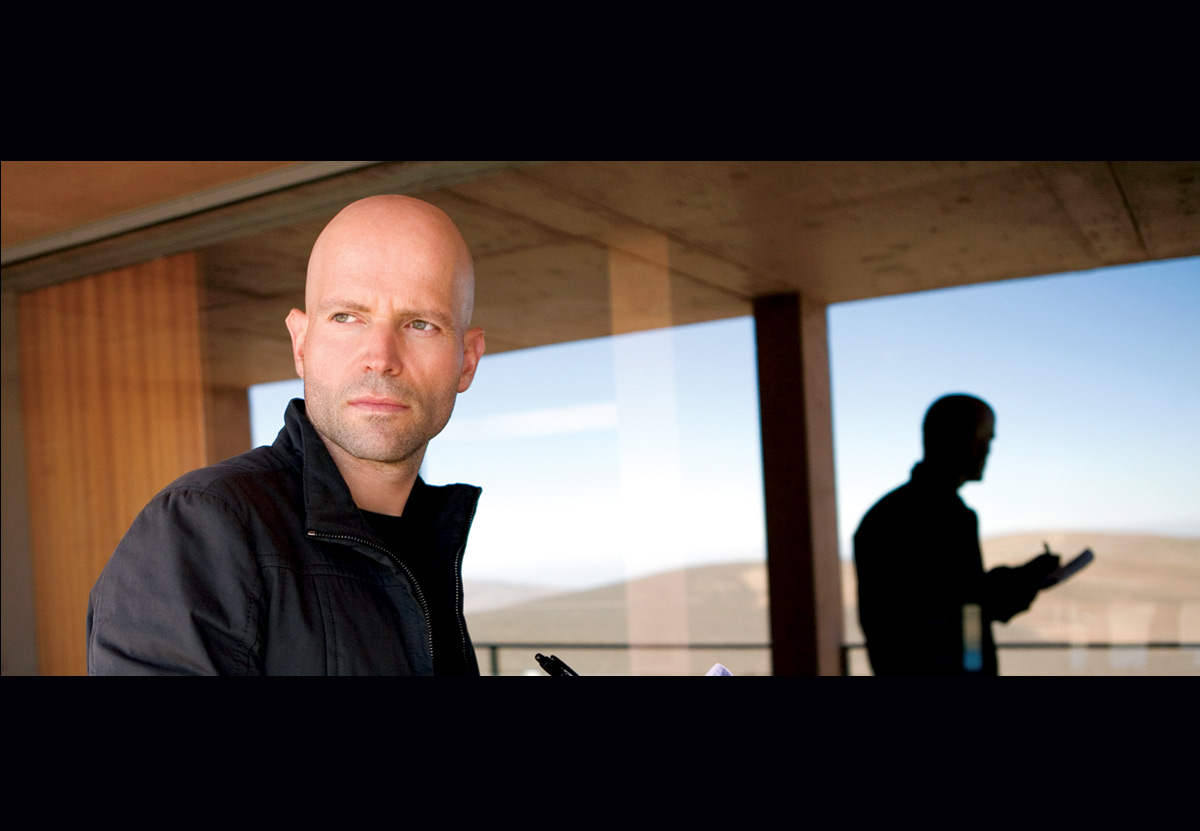

But with this 22nd Eon-produced adventure, Quantum of Solace (one of the few Ian Fleming-penned 007 titles not yet used), producers Michael Wilson and Barbara Broccoli chose a different route, hiring indie/art film director Marc Forster, whose character-driven resume has ranged from Monster’s Ball to Finding Neverland, with zero pit-stops for conventional action-adventure.

Forster’s timing couldn’t have been better, as Quantum of Solace picks up right where 2006’s Casino Royale left off, the series now rebooted (with actor Daniel Craig) as a newly promoted 007 with plenty of hard edges, ala early Sean Connery or Timothy Dalton. Craig’s Bond is at an early stage in his career, lacking the infamous polish typified by Connery’s caveman-in-a-tux and original Bond director Terence Young. Developing that character further, as well as incorporating the larger-than-life scope of a Bond adventure were among the challenges Forster faced, as he sat down to talk with Kevin Martin during Quantum of Solace‘s post-production.

ICG: Taking on the follow-up to a revamped franchise like Bond seems like it might be a lose/lose, creatively at least. Marc Forster: I was at a point in my career where I could do pretty much any kind of film as long as it stayed in the $50-60 million range, with final cut and all the creative control I could want. So why risk making a big commercial $200 million film? If it failed, it could affect my ability to make the smaller films; if it succeeded, I’d just get offers for Hollywood blockbusters, which don’t really interest me. Plus, while they were locked into a release date, there was no script. I did feel it could be a lose/lose, but I did thank the producers for their interest.

ICG: What won you over? MF: It wasn’t till after the meeting that I realized there could be an upside. I mentioned the offer to my creative team [director of photography Roberto Schaefer, VFX supervisor Kevin Tod Haug and editor Matt Chesse], collaborators all who have each done so much to support my vision. Separately they all said, “you’re crazy, you’re turning down being a part of film history.” So I took their input into consideration. Then I read an article about Orson Welles, where he mentioned his only regret in life was not making a commercial movie. So I thought, maybe there is something to making a movie that will be seen by more people than all my previous work combined. It was an interesting dilemma; ultimately I realized that opportunity doesn’t always knock at your door, so my instinct told me to go for it.

ICG: How did you go through prep with Roberto Schaefer? Were things different than your previous collaborations because this time it was Bond? MF: I told the producers that I was going to approach it the same as any other project, like an art film. It may have a commercial audience built in, but I can’t make my films in any other way. I imagined what it would be like as a filmmaker to work under a repressive political regime: facing strong censorship, some very creative ideas can and often do arise. So even though I saw this as a direct continuation of someone else’s film, one made under the producers’ auspices, I could still be creative and true to myself while working within that framework.

ICG: Stranger Than Fiction seems set in our world, but with an overt element of the fantastic. Is Bond more a matter of being set in a fantastic world, with elements of reality grounding it? MF: Hmm, I suppose so. Bond locations are characters in themselves, so it was crucial to capture that aspect. I think director Terence Young’s Bond films did this well. [Production designer] Dennis Gasser and I flew around the world scouting even before the script was fully worked out. I chose locations purely on aesthetics; then we wound up writing bits around these locales tying them into the action.

ICG: Based on the trailer, your locations capture some of the early Bond flavor, something they didn’t always stick with in later films. There was an opera scene in The Living Daylights, but set at a traditional locale, whereas your Tosca opera has that huge eye on stage … MF: That eye is very compelling. They had done Tosca on stage in Austria, and we used it for a secret meeting that Bond eavesdrops on. The eye reflects a lot of iconic Bond imagery, such as the iris effect of the gun-barrel seen at the beginning of the films. Although this is a direct continuation of Casino, I tried to make it more like a ‘60s film in some ways. The work of [production designer] Ken Adam is a huge part of what makes those films work.

ICG: Your visual effects supervisor Kevin Haug mentioned your interest in architecture, and that your style runs toward Bauhaus. Is that reflected in the film’s design? MF: I wanted to mix differing architectural styles throughout, and in the Bond universe this kind of thing is permitted. Incorporating aspects from different eras also impacted the shooting. I love North By Northwest and The Parallax View, which are from different times but remain exciting to look at.

ICG: Roberto Schaefer cited Gordon Willis’ work on Parallax as a major influence on this, as well as 60’s-era spy films like The Quiller Memorandum and The Ipcress File. He said you wanted to avoid what he called the Bourne look, with shaky camerawork and overcutting. MF: Cutting fast to make up for a lack of excitement in the action isn’t what either of us wanted. We didn’t want to be divorced from the action either, where the other units would be doing something that didn’t match to our own style.

ICG: With all the turmoil Bond experiences, Roberto Schaefer said there was a chance to go very high-contrast on the imagery, i.e., really dark shadow work. MF: Part of the Bond tradition kept the character’s origin a mystery, but the last film changed that. I felt it was important to understand the shadow, the dark side of Bond. Is he just a hero? Is he operating only on a revenge motive or trying to figure out the larger issue of this secret organization? In the Cold War Bond films there was a clear line between good and bad. Now things are much more blurred, and it is harder to see where governments stand. Intelligence agencies operate under such a black cloud that good guys can be as bad as the bad guys, and vice versa. The power of politicians resides in large part with their nation’s resources, and that of course blurs the line between nations and corporations who own those resources. To walk that blurred line is interesting. For example, our villain accomplishes good things for the environment, but he does other things for his own capitalistic needs to enrich himself.

ICG: In fact, your hero looks incredibly bedraggled in some of the trailer shots, emotionally as well as physically; about as far from the cliché of James Bond in the spotless tux as you could go. MF: Exactly. The idea of Bond in the desert excited me because it was a visual representation of the state he finds himself in. Being isolated, lonely and without water brings out a certain desperation, so that was all good for putting the character across. I felt Bond was in such an interesting state — vulnerable, betrayed – and these were emotional components that I wanted to push further. If character weren’t at the core, it would all fall apart for me.

ICG: You originate on Kodak 35mm for most of the film, but one sequence employs several 4K Dalsa cameras to generate virtual camera moves. MF: Due to insurance, you can’t throw actors out of a plane; when you shoot them with fans in front of blue or green, it doesn’t look or feel real. But using this BodyFlight facility where people are doing it for real [suspended in air by powerful fans], the actors didn’t have to work at pretending to fall. You connect with their struggle from being in that wind tunnel, which reads so powerfully in the way it ripples their faces. The 4K virtual cameras let us get a variety of moves that would have otherwise been impossible to achieve, and these are cut with live close-ups of the actors shot in the tunnel. [See Quantum of Solace VFX story for details.]

ICG: Your more conventional work with actors — the kind that doesn’t involved hanging in a wind tunnel – included stars like Halle Berry, Sean Combs and Will Ferrell, sharing the screen with relative unknowns. How do you get all those big names to wind up on the same page together? MF: I love collaborating with actors to find a handle for what the part requires. In Will Ferrell’s case, I mentioned that his role would have been perfect for a toned-down Peter Sellers, and we also talked about Jacques Tati’s Playtime. Talking of tone and detail was enough so that when Will started, he got it right immediately. Every actor is different, but the goal is always the same; try to create a character who is naturalistic and believable, even when circumstances in the script might be slightly less than credible. [Laughs]