The best minds in technology at HPA 2024 all agreed AI will be a game-changer; less clear are where the new goalposts will be and what that event horizon looks like.

by David Geffner / Photos Courtesy of HPA

I arrived at the Westin Mission Hills Resort in Rancho Mirage, CA, early Tuesday morning, for the second day of the 2024 HPA (Hollywood Professional Association) Tech Retreat, and the writing was on the wall – or should I say: the digitally entered text that generated live-action video content loomed large on the venue’s three big display screens.

I’d missed the opening day’s session, kicked off by Seth Hallen, Managing Director of Light Iron and HPA President, along with HPA Board Members (as well as HPA TR-X Co-Chairs) Mark Chiolis (Mobile TV Group) and Craig German, themed around “extreme” workflows. By all accounts, Monday’s session – which included IMAX’s David and Patricia Keighley talking about setting up Oppenheimer for 70-mm celluloid distribution; SMPTE’s Renard Jenkins in conversation with Darryl Jefferson, SVP, Engineering & Technology, NBC Olympics & Sports; and an Extreme Sports panel that included Rob Hammer, SVP Broadcast & Studio Operations, for the World Surf League – was compelling and filled with industry players at the leading edge of live streaming and broadcast content. But it was mainly a prelude for Tuesday (and most every other session that followed), which dove deep into the hopes, wonders, and fears of AI, which nearly everyone at the Tech Retreat described as “the single biggest technological disruptor” since the advent of sound a century ago.

“We’re all intrigued by how these evolving technologies are reshaping our industry, impacting our workflows and processes, and the roles we play in that,” Hallen announced in his opening remarks for Tuesday’s Super Session, which deconstructed the making of the animated short film Ashen in the morning and then checked in with a group of artists and filmmakers behind the AI-animated short Trapped in a Dream after lunch. The final panel on Tuesday brought together participants from both projects to compare and contrast the leading edge of traditional filmmaking workflows (used for Ashen) with the promise (and current reality) of generative AI (used for Trapped in a Dream).

“When we started to engage with Niko Pueringer (co-founder of Corridor Digital, whose YouTube channel is infused with generative AI content), the learning began,” Hallen added. “And when we presented Niko with the script that [Ashen Director/Producer] Ruby Bell’s team was working on, that sparked an insightful revelation. While AI’s potential is undeniable, the narratives best suited to its strengths – at least as of today – require a different approach. AI is a new way of telling stories, so it wasn’t feasible to use the same script for both of today’s case studies.” Hallen noted that “what we came to realize [from conversations with Pueringer and other AI-focused filmmakers] set the stage for an adventure that is engaging, surprising and precisely what HPA’s Super Session is all about – to show, not just tell, how these new technologies – including the cloud workflow employed by a global team of filmmakers on Ashen – are impacting the business of storytelling.”

Along with Bell, writers Jack Flynn and Charlotte Lobdell, and VFX Producer/Animator Shaman Marya, Ashen’s team included ICG Director of Photography Mandy Walker, ASC, ACS, who came on as Executive Producer. Moderator Joachim “JZ” Zell (ACES Project Vice Chair at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Science) introduced Walker as “the person everyone knew when we went to Panavision, ARRI, Sony, and RED needing camera, lighting, or grip equipment for Tangent [the HPA 2021 Super Session short film also directed by Bell]. But now we’re in animation, and no one knows her in this area. And there was a lot of explaining to do. ‘So, Mandy, why did you get involved with this?’”

“As I was an executive producer on Tangent,” Walker shared, “I was excited to come back on another HPA film. I so appreciate the HPA’s support for filmmakers, and they were incredibly generous in facilitating this project we’re presenting today. It was a labor of love for everybody involved; and as the executive producer, I have to thank all the vendors and various people who helped us out. I’ve not had any experience in animation, so as a cinematographer, it was a learning opportunity. I had worked a little bit in virtual production on a movie with Shaman and [Ashen Virtual Camera Supervisor] Jackson [Hayes], and I brought them back.

“In my job on set,” Walker continued, “I am – more and more – interacting with visual effects. So understanding those tools in a cloud-based system, and working with a virtual camera that’s advancing all the time, as well as the Unreal game engine system that’s always getting better, is important to me as a cinematographer. Working all over the world, remotely, has been an exciting journey. A lot of people stepped up to do something they hadn’t done before, or they pushed themselves to use their experience in a new way. That’s been great to see.”

Walker, who earned an ASC Award and a 2023 Oscar nomination for Elvis, went on to caution the 1000-plus attendees at HPA that “what you are about to see [with Ashen] is a work in progress, and we still have a long way to go. So please be generous and open-minded,” she smiled. Zell then asked Walker if she or her agent had ever been approached by major animation producers, like Sony, Pixar, or Disney, to supervise the cinematic look for an animation project. “Is this happening?” he wondered. “Is this a thing?”

The DP replied that she did get asked “once, a long time ago. But, now, I wish it would happen more because I find it all incredibly interesting. The virtual production part of it, especially, is becoming more integrated into what we do as directors of photography. And getting involved, very early on, with the VFX Supervisor [on a new project] is becoming a standard thing. Understanding all of these new tools is important.”

To highlight Ashen’s complex preproduction process, Bell presented a series of slides that included lookbook imagery and environmental/character thematics. She explained that “a lot of us come from live action, so we had to lean on the skills we knew. We had to do a lot of rehearsals on Zoom, with our actors, who were all over the world. So, we needed to develop a visual language early on, so everyone had a sense of what a child’s horror film felt like.”

Marya, who’s worked extensively with Unreal Engine in his previsualization work, added that “the thing I’ve always struggled with is: how do we finish in Unreal Engine? That’s not a new conversation, but when Mandy and Ruby said, ‘We want to make an animated film and we don’t have any budget,” my response was: ‘I guess we have to finish in Unreal Engine. That’s the only way it will work.’ It seemed like a crazy idea, and we’re still only about 70 percent there.”

The VFX producer, who joined the project in the summer of 2022, was given character and environmental mock-ups by Bell, which he calls “the first sprinkling of generative AI to make its way into our workflow. Ruby had these great comps, and we had a concept artist coming in soon after,” Marya continued. “The idea was: how could we provide material to the concept artist that would elevate [the building of the characters and environments] to another level? I was two days away from canceling my [AI art generator] Midjourney subscription when Ruby asked for our help, and I was like: ‘Okay, I guess I’ll pay a little more.”

Global Strategy Leader, Content Production, Media and Entertainment for Amazon Web Services Katrina King supplied a key piece of Ashen’s workflow puzzle when she spoke to the audience about color finishing in the cloud. “Last year on this stage, Annie Chang said she thought that would be the last thing we addressed in fulfilling MovieLab’s 2030 Vision,” King said. “But I’m going to challenge that because, without the ability to finish in the cloud, it doesn’t make a whole lot of sense to ingest your assets in the first place. The next time you’re using them would be for VFX pulls, conform, and finishing. So moving all of that to the cloud [without finishing capabilities] would be akin to building a bridge to nowhere.”

King then ran down a visual presentation that revealed how AWS designed a comprehensive production/postproduction workflow for Ashen that included asset management and encoding, transport protocols, color grading, and more. “We did a Flame implementation with the framebuffer feeding to the Colorfront Screening Server,” she explained. “That supports 12-bit 444 input, streams over 10-bit over SRT, and encodes on the player side, using a Colorfont Streaming Player that’s routed through an HAA card – either 10- or 12-bit – to a reference monitor. The Colorfront Streaming Server also supports Dolby Vision tunneling.”

Pointing to the large room displays, King added, “This is the implementation we used for a Flame conform in the cloud to connect to a reference monitor. For color grading, we’re using Resolve, which leverages the Nvidia on-board encoder that feeds up to a 10-bit 444 encrypted signal over WebRTC to a client machine, which is then fed to a Blackmagic Design Decklink or Ultrastudio. The final mile is over copper SDI to the monitor itself.”

AWS Technologist Jack Wenzinger led off Tuesday’s afternoon session with thoughts about disruptive technology, noting that “JZ came up to me in 2019 to propose the [HPA short film project] Lost Lederhosen. Back then, the cloud was considered disruptive, but no one was sure what it did,” he recounted. “Game-engine technology was also coming into our space, and we weren’t sure what that meant for virtual production and VFX. We answered a lot of those questions that year. And since then, [HPA] has continued to bring forth projects that push the needle of innovation. We owe a lot of thanks to people like Mandy Walker, JZ, Ruby Bell, and the many cinematographers who have helped build this out.”

Wenzinger said the key to all of the HPA-featured projects has always been, “How do we go from disruption to adoption? Everyone’s wondering what generative AI is and how it will impact our industry. But disruption has always been there,” he continued. “All the innovation happens when we harness the disruptive technologies that are mature enough to create a new workflow. Have you ever once read about a new movie that’s come out where they said, ‘Yep. We did it exactly the same as the last one!’? That just doesn’t happen.”

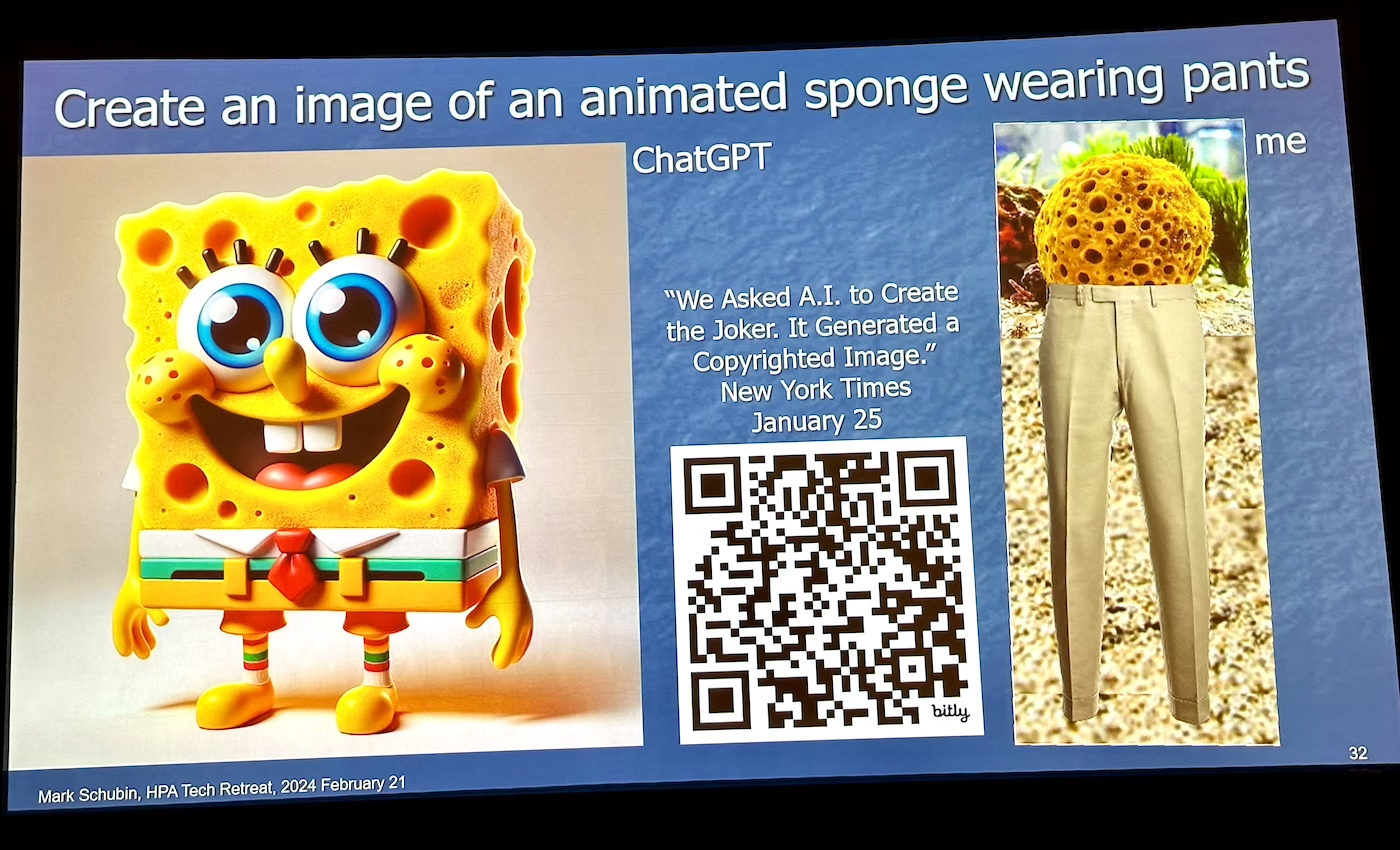

Corridor Digital’s Pueringer was next up, explaining that “AI software is changing so fast, the original idea Seth and Jack brought to me, about comparing a film like Ashen – created with leading-edge animation tools like CG, Unreal Engine, cloud management, et cetera – with an AI animation, which, in itself is a super-broad, non-specific designation, was not going to hold up. The AI-animated short [Trapped in a Dream] you’re going to see was created with software that came out three weeks ago! With such rapid change and an inherently experimental medium, it didn’t make sense to present a workflow that we couldn’t check back in on. The next best option was to showcase an experimental AI project and include on-stage demos, along with artists committed to the space who have a lot of experience.”

Pueringer said that one of the main goals of his HPA presentation was “to dispel all the hype about AI and show you tools that can be used right now in your pipelines. As I said, AI animation can be many things: a way to generate imagery, a way to generate motion, a way to render existing motion, a fancy filter to use for previsualization, and the list goes on. As long as it’s based on some sort of statistical machine learning model that’s giving you imagery, AI animation can be anything you want it to be.”

Describing AI animation as a “new software paradigm,” Pueringer added, “You guys are probably all used to non-linear editing, node-based and layer-based compositing, and various ways of managing your data. AI animation is a new piece of software that’s never existed because you need to have a way to manipulate and adjust these trained statistical models – to pull something out that is your creative vision. There’s no traditional workflow with AI, and the software is being developed open source by thousands of different users, with thousands of different goals. Which can lead to a few downsides. It’s very fast-moving, and mostly experimental, so things break all the time.

“What I’m showcasing today is centered around latent diffusion, a way of generating and understanding images in a machine learning model. This was a breakthrough that basically started with training a computer to de-noise an image. We add more noise, it takes it away until you are giving the computer pure noise – no image at all – and, as it turns out, the computer can imagine an image from all that noise.”

The AI short Trapped in a Dream was a psychedelic, color-saturated video meant to visualize the potential of AI tools in content creation. With a background in VFX, Pueringer detailed how “there are three ways for us to generate a visual asset at this point. Photograph it with a camera or physically render it, whether that’s digitally or with a paintbrush or a stick in the sand. The third way, which came to light in the 1990s, is computer renderings of geometry, aka CGI, 3D animation, et cetera. That’s pretty much it. Photography, illustration, or computer math. However, with AI, we have a fourth way of creating a visual asset, and that’s with a neural network, which is distinctly different from computational geometry. We’re looking at inference instead of calculations, imagination instead of math.”

Tim Simmons, whose background includes sharing an Oscar with the New Line Cinema team from Lord of the Rings, came onstage to supply a recent history of AI content creation. Simmons’ YouTube channel, Theoretically Media, aims to demystify AI in a way that’s accessible to creatives of all skill levels. “Because I come from the same traditional world of filmmaking that many of you do, I have created all my AI tutorials with that in mind.” Simmons presented various examples of generative AI content over the last two years, including Will Smith eating spaghetti, The Family Guy, and his own fake AI documentary that imagines a “lost film” in the Alien series directed by John Carpenter using voice cloning of British legend Michael Caine.

“The world changes when Runway Gen-2 AI is announced, and we all kind of lose our minds and feel, for a moment, that we all just stepped into the future,” Simmons added. “Synthetic Summer [created with Runway Gen-2] was an AI-generated beer commercial that went viral in May 2023; and while it was weird, it was also kind of awesome. In July 2023, a mysterious video appeared on the scene from an AI generator called Pica, and that was also equally weird and surreal. People discovered that if you play around with an area the AI model knows, you can get some remarkable results. The Dor Brothers did this with the video Can You Paint a Taste? The Dors figured out that Pica knew who Van Gogh was. You could prompt for actions in a Van Gogh style and end up getting something very cool.

“The Dors video runs at eight frames per second and yet is still very smooth looking. The next big leap, literally two weeks later, was image-to-video, and thus began the era of ‘parallaxing people staring at nothing,’” Simmons announced to much laughter. “The natural place people leaned into for this was making trailers, and one of the best early examples was Nicolas Neubert’s trailer for the sci-fi epic Genesis. But there started to be a backlash against generative AI as people were mostly doing the same thing and not using the tools to innovate. That’s when people like Sway Molina, using an early version of Kaiber AI, came along to add a lot more stylization to the technology. One of my favorites was a short film called Sh*t!, from Abelart, where everything is run through After Effects with tilt shift, out of focus, and camera shake, to create a much more cinematic look with generative AI.”

The last panel of the day, Bringing It All Together, was moderated by Hallen and included many of the participants from throughout the day. As Hallen noted: “A lot of people came up to me during the breaks today with questions that I couldn’t answer, so I’d like to open this up to our audience and have the panel help them out.” One attendee announced that “this is kind of a ‘bummer’ ethics question that has to be asked. Everyone has talked about how these new AI tools will democratize what it means to be creative. But for those who are trailblazing AI, how do you ensure that the knowledge created by those who pioneered all of these filmmaking techniques AI is building on is carried forward? Eventually, if it’s model on model, how do we source that knowledge back?”

Caleb Ward, who along with his wife, Shelby Ward, runs Curious Refuge, an online platform pioneering the use of AI in filmmaking, said the best AI films they’ve seen through their online school have come from “people who have preexisting skillsets in storytelling. We feel these tools will become even more user-facing and easier to use so that people who are classically trained can take these tools, contextualize them, and learn how to supplement their work to get even more content out there.”

Notably, just before the start of the 2024 Tech Retreat, OpenAI debuted its new text-to-video generator Sora. A demo of Sora onstage at HPA was impressive, with various environments portrayed – a woman walking down a rain-washed Tokyo street at night, a spotted Dalmatian dog leaning out a window on a street with richly saturated colored houses, a cat gently nuzzling its sleeping master in bed, and more. While the initial reaction was positive, with many HPA attendees expressing surprise at how realistic the generative AI looked, that was quickly followed by questions of caution, fear, and even trepidation that Sora (and others to follow) may supplant a century of traditional filmmaking. (Not coincidentally, the CEO and COO of OpenAI, Sam Altman and Brad Lightcap, gave demos of Sora to representatives of at least three Hollywood studios a month after HPA, to quash fears that was OpenAI’s intent.)

There’s no doubt Sora’s text-to-video generation was better than anything generative AI has yet produced. But thankfully, the final two days of sessions at HPA – while still AI-heavy – included many filmmaking veterans intent on updating attendees on advances in capture and on-set technology that uphold Hollywood’s human-driven production model, one not ready to be taken over by machine learning anytime soon.

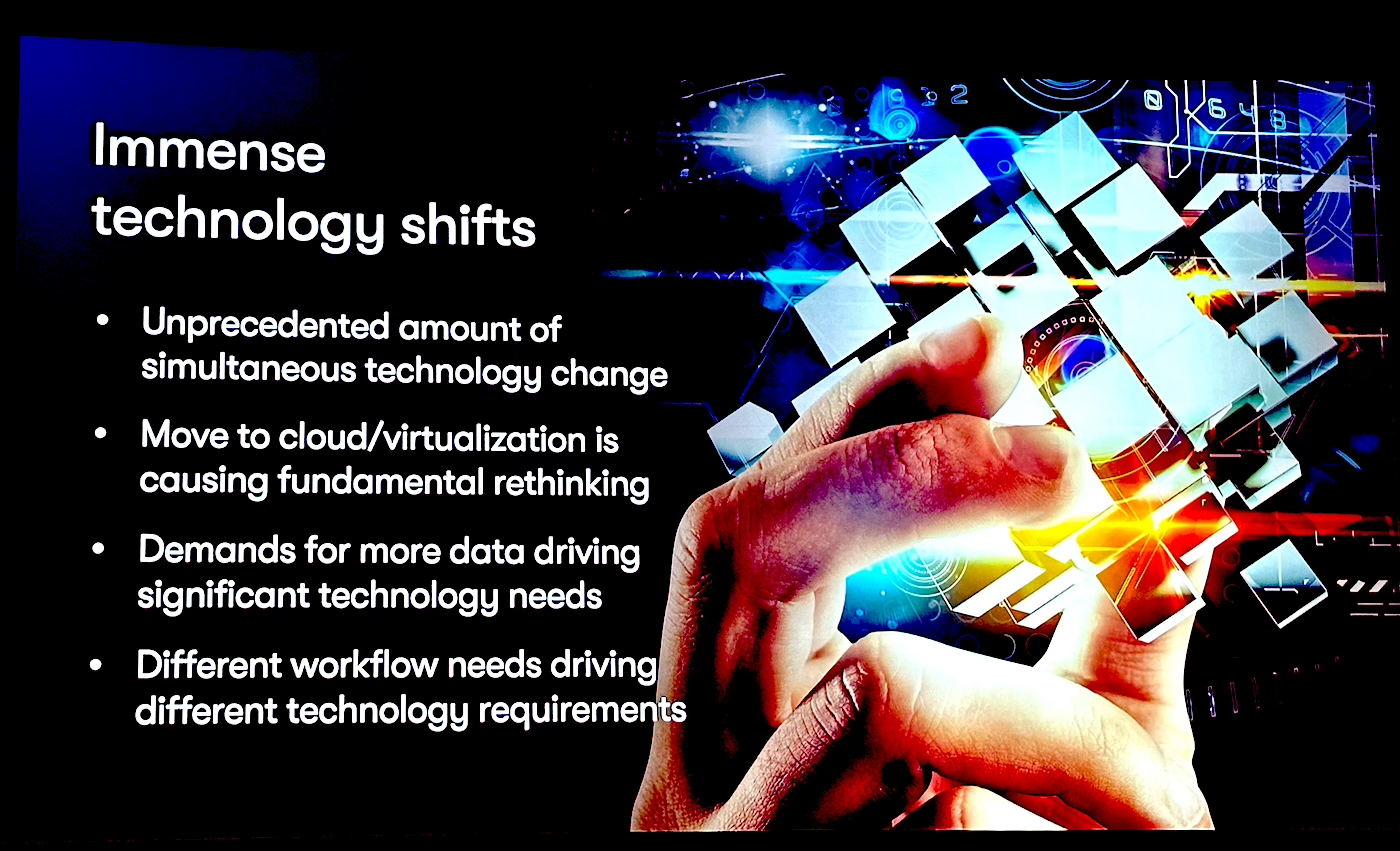

That included Mark Harrison, CEO of DPP, an international network for media and technology Harrison founded that counts more than 500 companies as members – from global tech giants to broadcasters, and from media tech vendors to production companies. Harrison’s annual role at HPA is to report back on the trends he sees at CES (Consumer Electronics Show), many of which are precursors to tech innovations in the professional space.

“With the lines between business and consumer technology blurred,” Harrison announced during his PowerPoint presentation, “CES is an opportunity to take stock of where we are in the global battle for a finite resource, which is the time, attention, and money of consumers. Where are we on that battlefield?” Harrison turned to a slide representing the last 20 years of original content created in the U.S. alone, “which,” he pointed out, “increased 10-fold, year-over-year, creating an unsustainable bubble. This bubble burst before the SAG and WGA strikes. And when times are tough and revenues are down, what’s the other thing that has to come down? Cost. So after years of seeing companies pitch innovation at CES that encourages us to spend money, we are now seeing innovation that, potentially, encourages us to save it.”

Other Wednesday sessions included “New Developments in Open Source Software for the Motion Picture Industry,” moderated by David Morin (Academy Software Foundation) and featuring professionals from Autodesk, AWS, Netflix, Frame.io and Foundry, and Eluvio’s Michel Munson discussing Content Authenticity and Provenance: Protocol versus Workflow.

Morin opened with a recollection from his breakfast roundtable earlier that morning about workflow. “I was speaking with a post supervisor who told me that when a shot is cut from a movie, you want them to stop working immediately because that saves tons of money. That sounds obvious, but it’s often not the case. Because of the complexity of pipelines, people will keep working on a shot that’s been cut from a movie for quite some time. So we have on this panel people who are close to the ground and working to improve these kinds of workflows, particularly trying to enable the interoperability aspect we’ll be talking about today.”

Munson, co-creator of the content fabric protocol, an open and decentralized Internet protocol for owner-controlled streaming, storage, and monetization of digital content at scale, is an Emmy-award-winning technologist who previously co-founded Aspera in 2004 and led the company as CEO until May 2017, including through acquisition by IBM in 2014. Munson, who co-invented the Aspera FASP™ transport technology, told the room she wanted to “tackle this topic for obvious reasons, given the theme this year of both the threat – and the opportunity – of large language models, generative AI, and their impact on the creative industry. I also want to tell you a little bit about the backstory of the community around that of the last year. I want to frame this with a certain point of view, and timeclock, which is end-to-end design that is the foundation and bedrock of how the internet was built.”

Tony Guarino, Head of Paramount Global’s Production and Studio Technology Group, talked about how his team at the studio is onboarding new and emerging technologies in the production space, including generative AI applications for content creation. “Regarding Gen AI,” Guarino announced, “2023 was the beginning of a lot of discovery and some experimentation for us, and 2024 is shaping up to be heavy experimentation and preparing onboarding and tooling for the creative community. AI will have a major impact on our studio as well as all the other major Hollywood studios. I’m here today to talk about responsible AI, from the studio perspective, and how it’s impacting the content creation lifecycle. Used properly, gen AI can be a tool to assist creators by augmenting and enhancing their ideation. Also working in the background, for example, embedded in workflow software, it can speed up creators’ ability to get their work done faster, and, ultimately, reach audiences faster as a result.”

The final day at HPA began with Jim Helman, CTO of the nonprofit MovieLabs (a joint venture of five major Hollywood studios that has put forth a 2030 vision plan for media creation in the cloud), moderating a panel on enabling interoperable workflows. It included technology experts from Universal, The Walt Disney Studios, Adobe, and Autodesk. Following that discussion was a Local 600-sponsored panel titled “Stepping Up to Color Managed On-set HDR/SDR Workflows.” Moderated by ICG Technology Expert Michael Chambliss, the conversation featured Greg Smokler, VP/GM of Cine Products at Videndum Creative Solutions, whose product teams include Teradek Cine, SmallHD, and Wooden Camera; Rory Gordon, Supervising Colorist for ArsenalFX, who has finished more than 130 episodes of television in HDR10 and Dolby Vision; and ICG Director of Photography Tommy Maddox-Upshaw, ASC, whose Hulu series Snowfall won an ASC Award for Best Cinematography for a One-Hour TV Series, making Maddox-Upshaw the first black ASC member ever to win the honor.

Chambliss got the discussion going by referencing an HDR projection demo from Barco from Monday night that, “portaging an HDR image from a smaller envelope, like a Rec.709 container into a P3/PQ HDR space, can reveal a host of issues,” he explained. “But the forward march of intrepid engineers is making on-set HDR monitoring and color-managed HDR workflows an efficient way of preserving creative intent, as well as keeping that intent through the pipeline with both SDR and HDR dailies and on through postproduction. HDR has been around for a while now, so we’ve assembled this panel of really smart folks to tell us why we can do something we couldn’t do four years ago.”

Smokler was first to reply, noting that “we’ve been capturing in HDR for some time, and finishing in HDR for a decade-plus. But throughout this time, cinematographers never could see full [native] HDR during the capture phase. For us at SmallHD, we’ve always been focused on making small, portable, very rugged monitors that are extremely useful for framing and analyzing exposure, ultra-bright with a rich software feature set, et cetera. But we didn’t tackle the ‘shooting for the stars’ goal of making displays that were reference-quality-ready and worthy of judging a final image on set. We’ve had the capacity and expertise, but we didn’t start until about five years ago. The goal was a 1000-nit HDR monitor that could go anywhere in the world filmmakers need to go, and would have all the requisite software tools.”

Chambliss quizzed Smokler about any feedback he’s gotten, “about the types of things that need to be built into the software since the monitor has become not just an extension of the viewfinder but much more of a high-end production tool.” Smokler replied that for SmallHD, “We take a holistic approach to the technology, with custom-designed platforms that make the software user experience in harmony with all of the engineering that goes into the electronics. That enables us to have this ultra-rich operating system that creators and technicians can utilize and customize in an endless way on set. From a tools perspective and software, the things that allow cinematographers to get their lighting levels/ratios done quickly. These are the same tools you might find in a color bay to assess and dial in things to be incredibly accurate. We want to bring those tools to the fingertips of a cinematographer to allow them to deploy them in the specific, bespoke way they want to for every production.”

Maddox-Upshaw, who just finished a film that used an HDR/SDR color-managed workflow, spoke about how that changed his process on set. “The impact with the HDR workflow starts in prep and doing a camera test, where my final colorist is involved as we structure the LUT,” he began. “Seeing how far the roll-off is, and the highlights, and how much more on the bottom end we can see. With the construction of the LUT, I have art department and wardrobe examples in the frame, and in the camera test, I can see the high and low points and the color shifts. Seeing HDR/SDR simultaneously, and seeing that the HDR is more saturated, I know I can always come down off that HDR peak for the final product if needed. So to see all the HDR and SDR values on a set is a great advantage, but to have it pay off, it all starts in prep.”

Chambliss added that “what Tommy is referencing is a conversation we had just before this panel about the challenges cinematographers have when monitoring on set.” “That’s right,” Maddox-Upshaw picked up. “Evaluating footage on set, we’re not always in the most pleasant viewing environments, in which case you have to fly by the instruments, the values of the monitor. The numbers and values are dictated by the final colorist in terms of the LUT construction, the gamma curve, and all that we established in prep. I’m always metering those values from the waveform [or other features on the monitor] and aiming for the nit values of the high IREs in terms of skin values and highlight blowout points. If I’m out on a bright sunny day, I’m aiming for those value numbers that have been determined by the final colorist and myself for the final image to look a certain way. I can be flying the airplane by the instruments while [the colorist] is in the tower telling me to ‘pull up,’” he laughs. “It comes down to the parameters you set up in prep with your color scientist to make it all work.”

Colorist Gordon quickly added, “We live in a multiple-color-target world now. That’s the big difference now from five years ago. One of the first shows at Arsenal that used on-set monitoring was Raising Dion, and that was with [AJA Video Systems’] FS-HDR. Colorfront’s engine was in that rack as well so you had an SDR feed, an HDR feed, and a Rec.2020 container, which was required [by Netflix]. But now I think color management has gotten to the point where, in the LUT design, we can make choices that allow us to have easy parody with the LUTs we send to set. As Tommy was saying, if we know we’re going to want to rescue detail from a specific situation on set, or we’re pretty close to the walls and we don’t want to have detail in this situation. The biggest difference now – from five years ago – is that we now live in a world where both an SDR and an HDR color target can coexist.”

ICG Director of Photography Andrew Shulkind [ICG Magazine April 2024], who is SVP Capture & Innovation at MSG Sphere Studios, put an exciting technological button to the end of the Tech Retreat, with his thoughts during a panel about the making of Postcard from Earth, which was directed by Oscar-nominee Darren Aronofsky as the first film ever to screen at Sphere in Las Vegas. The panel, which included Picture Shop Colorist Tim Stipan and Picture Shop President Cara Sheppard; along with Josh Grow, Senior Vice President, Studio Core Technology at Sphere Entertainment, and Toby Gallo, Digital Intermediate Pipeline Supervisor at Sphere Studios; broke down a film that was so groundbreaking, it required creating a capture device, pipeline, and proof of concept process that had all never been tried.

Moderator Carolyn Giardina prefaced the panel by noting that “Sphere is a 60,000-square-foot 16K LED display, that if you haven’t seen it, and you are going to NAB, it needs to be seen in person as it’s difficult to explain what the Sphere experience is like. This film, which last night won an award [Outstanding Visual Effects in a Special Venue Project] at the Visual Effects Society Awards, takes viewers on a trip around the world, and is bookended by a space-set story that’s presented in a different aspect ratio from the rest of the project.”

When Giardina asked Shulkind to break down the many challenges inherent in shooting and posting a film for the world’s largest viewing venue, Shulkind smiled and said, “I’d love to. And we call [those challenges] ‘opportunities.’ As Carolyn described, the interior screen is 16K by 16K, so 16.384 by 16.384, and no camera could provide a one-to-one image for that – until we designed and built it. One of the biggest challenges was that the screen didn’t turn on until July. We finished shooting in August. So, we weren’t able to proof any of our work until the venue opened [in September 2023]. The venue, and the way we photographed for it, is 60 frames per second, so our baseline frame rate and our aspect ratio were basically one-to-one because we’re photographing inside of a fisheye. Sphere seemed like the craziest idea, being built during COVID. And then suddenly, it became something really important, as we all realized the power of the collective experience. If you go see the U2 concert, or Postcard, or any of the things that are coming, I think that’s obvious by the crowds of people that go who are enthralled by [the Sphere experience].”

Shulkind went on to break down the one-of-a-kind camera built for Sphere. “We recorded to 32 terabyte mags, in 18K by 18K, with the idea that some of the wasted pixels would be on the outside as we were putting a circle inside of a square. It was an incredible achievement, designed and built by Deanan DaSilva [Camera, Optics, Display, and Imaging Systems Product Development and Strategy for MSG] and some great people we have internally. I think the theme of this discussion, and the expertise everyone here brings, is that the technologies we’ve been applying to create something for this venue didn’t exist before, and often weren’t ever applied to the motion picture industry. Pulling these different tools from various places to figure out what works is part of what excites us. But also the heart of this project. That has to do with [image] stabilization, data storage, frame rate, color, and the way the screens weren’t profiled. Everything we were dealing with was new.”

Ironically (given how much of the conference was given over to the potential power of machine learning), Shulkind’s words about the importance of the collective human experience were reflected consistently throughout my three days at the HPA Tech Retreat. Yes, AI has arrived, and it may well impose some far-reaching and radical changes on the entertainment industry, the likes of which many HPA attendees have not even seen in their lifetimes. But, for me, the imprint of just how key union craftspeople are to the process of content creation, and why AI will never supplant human labor, came after ICG’s Color Managed Workflows panel ended, and ICG Director of Photography Maddox-Upshaw was surrounded by attendees. Maddox-Upshaw’s real-world experience and talent were the big draw that day, besieged with questions and requests for selfies as he was. One attendee turned to me and said, “It’s so great when we can hear about all the new and emerging technology directly from the filmmakers.”