Greig Fraser, ACS, ASC, explores dark new worlds for Denis Villeneuve’s newest incarnation of Frank Herbert’s celebrated novel, Dune.

by Kevin H. Martin / Photos by Chiabella James / Warner Bros. Pictures

Classics of sci-fi literature have proven to be challenging source material when it comes to film adaptations. In the case of Frank Herbert’s Dune, an interplanetary adventure that delved into nascent ecological concerns while offering a study of Messiahdom, the 1965 novel drew considerable Hollywood interest, fueled further by the pop-culture fervor for Herbert’s sequels. After false starts with some notable filmmakers, the project fell to David Lynch. Released in 1984, the visually striking adaptation (shot by Freddie Francis, BSC) failed to thrill movie audiences or Herbert devotees. A 2001 miniseries (shot by Vittorio Storaro, ASC, AIC), while more faithful to the novel, suffered from budgetary considerations that kept it largely stagebound.

Denis Villeneuve, a fan of the book since his teens, eagerly seized the reins for this new incarnation, which covers roughly the first half of the novel. Villeneuve re-teamed with several past collaborators, including Editor Joe Walker, Production Designer Patrice Vermette, Special Effects Supervisor Gerd Nefzer and VFX Supervisor Paul Lambert. Joining them was Oscar-nominee Greig Fraser, ACS, ASC, who had filmed his share of desert worlds for Disney’s The Mandalorian [ICG Magazine April 2020], though those employed virtual production instead of the extensive location work utilized for Dune.

“Through CG, worlds can be created infinitely large in scale, but we always tried to look for the best ways to service the story,” Fraser relates, “The novel by its very nature was a complex beast, one that caused problems with past attempts to make Dune, along with the variety of environments mandated.”

Fraser says he was impressed by the results achieved from the Villeneuve/Vermette team-up for Arrival (shot by Bradford Young, ASC) on a relatively modest budget. For Dune, Vermette enjoyed a lengthy prep that enabled him to work out the visual details of the many planets and vessels as well as the lifeforms populating them. “Denis offers his collaborators freedom in making their contributions, so there’s never a feeling of constraint when it comes to voicing an idea,” Vermette explains. “After I showed him some early material based on the script draft, he shared some of his scribbles, and it was clear we were on the same page, architecturally speaking. We were both striving to achieve a feeling with our imagery, something like Richard Avedon’s black-and-white photography inspires in a viewer.”

In fact, a full seven months were spent on conceptual artwork. “We start with a sketch and then a 3D model,” Vermette continues. “Even in wireframe form, I’m already asking where the light is coming from. With the model, it is easy to zoom-in to view details. I also orbit around the model to find interesting angles, which is going to be significant on set later, since everybody can see which angles look best and plan accordingly.”

Early concept art revealed the differences between the harsh desert dune world of Arrakis and Caladan, home planet to the Atreides clan, including young Paul (Timothée Chalamet.) “Portraying differences in culture is achieved through economics and landscapes,” Vermette adds. “Caladan is a blue and green world, a planet of water and island cliffsides, where there is always mist.” Vermette’s architecture for the city of Arrakeen is designed to look as though the structures could withstand 800 km/hour winds. Somewhat utilitarian in appearance, the city buildings were inspired to a degree by the look of WWII bunkers – about as removed from the moist comfort of Caladan as one could imagine.

“Normally the artwork is used to get the conversation going,” Fraser describes. “But this was so precise and wonderful that my main challenge was to honor those designs and intentions. I took massive inspiration for the lighting from the conceptual art, attempting to recreate what was on paper in a way that would be achievable on set.”

The level of preplanning allowed department heads, including Nefzer, to organize teams with great efficiency. “If there isn’t enough prep time, you inevitably face compromises, and often things won’t work as well as when you have time to plan things out,” he says. “But with Denis, everybody knows what is needed well in advance of shooting. That’s not to say he doesn’t have on-set inspirations; but I had an on-set crew taking care of everyday work, in addition to specialist groups handling flying rigs and pyro, so if Denis decides to add steam or drifting dust to a scene, we can often devise an on-the-spot practical solution. And there’s always the option to handle it later through visual effects.”

VFX supervisor Paul Lambert, who shared an Oscar with Nefzer for Villeneuve’s Blade Runner 2049 [ICG Magazine October 2017], agrees with Fraser about the usefulness of comprehensive artwork. “My collaboration with Greig was one of the most critical associations on this film,” he states. “Since we knew what the background would be and how the lighting was going to bake in, we met every day during preproduction to produce some inspired ideas. For example, we put a sand-colored screen on our backlot in Budapest. Everything on the planet was going to be that color, so our light hitting the screen would reflect an appropriate hue, instead of blue or green screen where you’ve got the wrong values. By inverting the sand screen in post, Double Negative could still do matte extractions, as the sand-colored screens effectively became blue-colored screens but without the limitations of having shot blue screen on set.”

Fraser’s camera testing ranged from 35- and 65-mm film to the large-format ALEXA 65. Fotokem DI Colorist Dave Cole remembers that “the grit and sand seemed rife with problems for shooting 65 millimeter. We thought 35 millimeterwould win out, but for desert scenes, the stock was too grainy, given we intended to do a lot of IMAX work.” (Along with Top Gun: Maverick, Dune was among the first films to shoot with IMAX certification.)

Other factors mitigated against celluloid. “For Denis, film felt too nostalgic, almost like telling the story while in the past, and this story is set in the future,” Fraser notes. “I’ve shot ALEXA since Zero Dark Thirty, so we went with the LF and Mini, which responded well in both extremes of climate: the desert scenes shot in Jordan and Abu Dhabi as well as the very wet Norway shoot for Caladan. The LF also let me go up to ASA 2000 without any noise issues.” Camera prep was at Panavision Woodland Hills, where Dan Sasaki performed his typical wonders in refining lenses to fit production’s needs. Panavision H-series and Ultra Vista lenses were used on both ALEXAs throughout.

Given the title planet’s arid conditions, the filmmakers avoided saturated colors and a classic blue sky/yellow soil palette. “Denis wanted a bleached-out look, so Dave built us a LUT that gave us a white-sky desert,” Fraser elaborates. “We tried a straight bleach bypass, but that was too much like Jarhead [shot by Roger Deakins, ASC, BSC], which wasn’t quite where we wanted to be.”

Cole recalls that Fraser came up with a still image that all parties accepted as a look for the desert, one using highlights from the bleach-bypass LUT, combined with a different look in the shadows. “Our modified skip-bleach look’s customization was done to keep the low end from getting too contrasty. If you’re on the driest planet in the universe, unprotected, you will die – and quickly, before there’s a chance to run into sandworm creatures or anything else.” Interiors used a separate LUT. “The day interiors are lit by sunlight pouring in through massive slits. As a viewer, you will ‘iris open’ on these interiors, but then upon cutting outside, you again feel the burn and heat of the ferocious sun on this bleak planet.”

While VFX would create set extensions to extend vast interiors, the art department helped Fraser by creating volumes on set that suggested what was to be added later. “We built these pieces in appropriate colors from flat fabric that Greig could light through,” Vermette describes. “If there were supposed to be beams extending up out of frame, we built those from fabric as well, to create a light/shadow aspect. This element would still need to be clad in post, but if the camera tilted up, it would again see correct color and texture.”

Fraser cites the ingenious design of the Budapest stages, which were built out of concrete, with speedrail rigging extending to their exteriors. “That is what allowed us to build this outdoor stage,” he explains, “which was like a huge silo, topped with a star-shaped gobo that let us light with the actual sun. We could never have found a big enough light to illuminate down to the floor. My assistant, Nicholas Turner, and I had done light studies so we knew when the sun would be in the right position to achieve this series of shots. We scaled it so the amount of sunlight admitted matched what the theoretical ceiling would be, at 200 feet in height, even though ours was only 40 feet above the ground.”

Ideally, Fraser adds, the gobo would have been a proper rigid structure. “But there was no infrastructure to achieve such scale,” he continues. “Instead, the Budapest riggers used lines so it could be let out like a sail. The wind was a problem, but we were able to keep it taut most of the time. To succeed, the gobo required successful collaboration between the art and electrical departments.” Transforming the Origo Film Studios backlot into a match for the deep desert required an exhaustive search for the proper shade of reddish-brown Jordanian dust that was also safe for cast and crew.

Save for the large-scale action scenes, Dune was primarily shot single camera. “There’s virtually nothing in the way of unmotivated camera movement,” Fraser shares. “All of the camera motion is quite considered, so we’re moving with the characters as they proceed through their environment.” Fraser operated A-camera himself, often using a “fantastic” KFD Aurora remote head that let him sit beside Villeneuve during scenes.

Camera Operator/Steadicam Operator Bela Trutz, SOC, came on during the Jordan shoot. “On location, lots of the sequences were handheld, as well as many with crane and dolly,” Trutz recalls. “The few times on Steadicam were a challenge using the ALEXA LT studio body, but doable. The second unit was more like a splinter, shooting sequences at different times of the day for the best lighting setup, [and] I did join them on a couple of occasions.”

Second unit Director of Photography Katelin Arizmendi’s credits reflect her experience in the indie sector [ICG Magazine January 2020], and she readily admits, “I didn’t know much about second unit, though the idea of working closely with Greig and Denis to ensure the shoot stayed cohesive throughout was appealing. Greig gave me a lot of freedom to go after whatever looked interesting when shooting pickups.”

One example was “over the Duke’s back that could be done using a body double,” Arizmendi describes, “and Denis wanted to capture a unique refracted light coming through the window. We got to spend six hours breaking mirrors and cutting up weird gels to get this unusual light spilling in and across the wall. Then I got to shoot some 16-millimeter footage while in Jordan. Paul views a documentary about Arrakis, and my stuff – mostly long-lens views of Fremen in the desert – after being pushed two stops, was used as the projected image.”

Arizmendi says there was previsualization for scenes featuring VFX and crowds, “and enhancing explosion scenes was a lot of fun for me and my gaffer. Using [Chroma-Q] Studio Forces and a dimmer board let us refine interactivity motivated by the blasts. There were huge softboxes up above when pyro was involved, so we could dial everything up and allow the explosions to expose correctly instead of blowing out the image.”

Shots of the aerial craft [mock-up] blowing up were reset for multiple explosions, because, as Nefzer describes, “we created fireballs instead of blowing the ships up for real, and then the ships were added in CG. We did some blasts on the ground, with others up on scaffolds as if the ships were flying by and could reset quickly for additional takes.”

Nefzer faced an elaborate challenge for a scene when Paul and his mother Jessica (Rebecca Ferguson) crash-land in the deep desert, just before their close encounters with a huge sandworm and Fremen natives. “We built a special sled rig because Denis wanted to see the approach and impact from within the cockpit,” Nefzer continues. “The challenge with towing this thing through impact was that real sand would be too heavy, so we used a kind of wheat called spelt. We put a plow with steel sheets on the ship’s front that guided the spelt dust over the cockpit. We had seventy meters to get up to speed – 50 to 60 kilometers per hour for the crash, and the ship, after leaving our sled, traveled 150 feet through our sandpit.”

Other full-sized mockups, built in the U.K. and disassembled and shipped to the location, were also facilitated by Nefzer and BGI. A combination of gimbals and cranes allowed the craft – “ornithopters” in Dune vernacular – to move on multiple axes, and a landing ramp was made practical through hydraulics. Fraser, a recent convert to RGB LED tech, relied extensively on Digital Sputniks and Creamsource units to create “headlights” for aircraft.

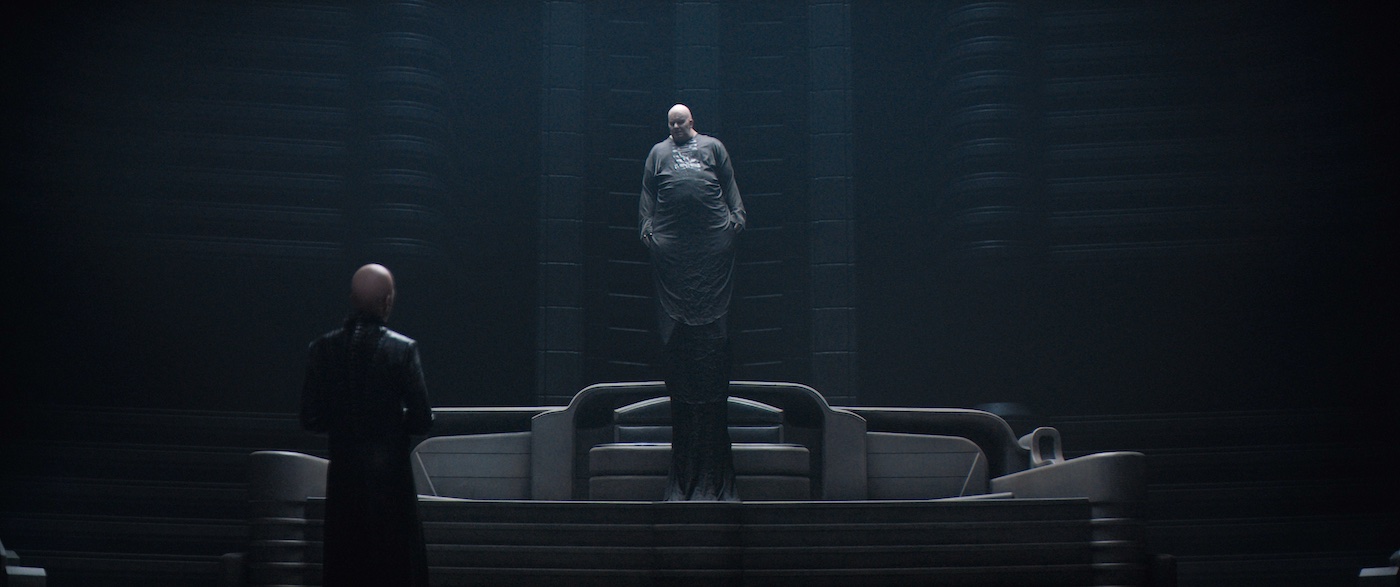

“Being able to refine color on-stage instead of just in the grade is very helpful,” Fraser notes. “We could put them on scaffolding or hang them off cranes; the arrival of Reverend Mother (Charlotte Rampling) was a moment we wanted to dramatize with lighting emanating from her ship, which was achieved with Sputniks.”

The other flying component fell to Aerial Director of Photography Dylan Goss, a veteran of two past Villeneuve films. “Greig’s dailies were truly memorable, in the best sense of the word,” Goss recounts. “His choices were so daring, with respect to the number of inky blacks and also the use of short-focus. We wanted to be in that same world with him visually, so we used heavy ND and Greig’s regular prime focal lengths.”

Working with aerial coordinator Cliff Fleming and camera tech Eric Dvorsky, who saw to the K1 Shotover system provided by Team5 Aerial Systems, Goss flew a military helicopter in Jordan (private aircraft are not permitted), often using the same technique employed on Blade Runner 2049, where he shot copter-to-copter for scenes that would later have VFX ships replacing the practical aircraft.

As Goss describes the challenging workflow: “When the instruction is that you follow a ship swooping by and darting down, it’s pretty hard to figure out where to shoot and for how long if you just have an empty frame. Our proxies were MD-500s, small five-bladed copters that already look a little like insects, and a lot like the film’s ornithopters. We spent some time building lighting rigs with cross beams on the proxy, which is a great in-camera way to get the right interactives; you’d see the mushrooming dust effect during a descent.”

Besides working to a shot list, Goss would occasionally get “free mission” days. “That meant I could go off and hunt stuff, a liberty afforded me by Denis’ faith,” Goss emphasizes. “He liked some unique formations we happened over – in those desert canyons, there were formations thousands of meters high, actual monoliths.” There was also a multi-camera array assembled and flown when shooting in Abu Dhabi, facilitating background imagery for cockpit scenes, operated through a Semote wireless camera menu control.

After an abortive attempt to shoot Norway-for-Caladan during an unusually warm summer, Goss returned in fall. “In terms of embracing atmospherics, the ‘put your money where your mouth is’ moment came in Norway,” he declares. “Caladan is extremely verdant, so it was more than just filming water – we needed to feel a constant surrounding mist as well as rain. So, we flew with a rain spinner on the K1 – water with a side of water!”

While in-camera was always the goal, Dune still relied upon extensive VFX, which were based on live-action aspects whenever possible. One example is when Paul is pursued by a hunter-seeker device sent to eliminate him and hides within a holograph of vegetation.

“We devised a technique that allowed us to track the actor on set,” Lambert recalls. “Knowing where he would be in the physical space, we used a projector to put a slice of this holographic bush onto him. The projector updated that image with each subsequent frame as he walked through it. Projecting real lighting onto Paul worked out well, and while there were CG aspects to the shot, the lighting and interaction were real and integrated perfectly.”

What would Dune be without the planet’s most famous inhabitants, the huge sandworms living in the ground? “There isn’t much existing reference for things that big disturbing sand,” Lambert admits. “I did request that Production detonate some explosions in the desert to get a real-life reference but given that we were shooting in the Middle East, that kind of thing could be mistaken for an attack and was frowned upon!” Consequently, procedurally based simulations were used to generate the wake of the worm and much of its interactions.

Once the film was in post, Fraser cut together a color bible with the assistant editor, including a wide and close view from each scene. “That ensured we wouldn’t need to make a lot of changes in the final grade,” he states. Cole had done the majority of his past work on Lustre but here used Da Vinci’s Resolve. “We include Arrakis’ two moons in the sky,” Cole notes, “which are small, but in some night scenes, they register sufficiently that you will see multiple shadows. A lot of the end of the movie takes place in dark conditions, but you can still see everything. There was intense rotoscoping needed to ensure you could see eyes and faces. We rode a very fine line between pre-dawn darkness and the point after the sun rises. It’s not a sci-fi lit thing, with lurid neon, but instead, like just about everything on this, was very well thought-out, like the changes in aspect ratio; something over half of the movie is 1.43, including the whole last stretch of the movie.”

There was one new step added to postproduction, an innovation that first occurred to Fraser while shooting Vice. “I thought that after the DI, we could spin the final out to film before scanning neg back in,” he says. “The idea was to see if that got us back some of the intrinsic beauty of film, specifically its contrast range and how it exposes highlights. We discovered that it also served to take the digital edge off the bright sun highlights.”

Cole and Fraser had tried the approach before on a music video. “We found shooting to a digital negative that has the exposure level of 1 ASA, like a dupe stock and with the smallest possible amount of grain, was very similar to what true 15-perf, originated-on-film looked like when you put them up on IMAX screens,” the colorist reveals. “It wasn’t about grain per se, but all the aspects that one might describe as film artifacts: interlayer halation, the nonlinearity of density across the frame and even allowing some dust to come through. The weave, blur, and slight density breathing of film – the latter is something we had tried emulating digitally – were organic qualities that in the past we did everything possible to mitigate against, but here we were trying to bring them to the fore since they don’t exist in digital. They added a sense of life, especially in the 1:1.43 aspect ratio, and that includes the many VFX shots, which, while they were the best I’ve ever seen, still benefited from this.”

Posting Dune at FotoKem – a film lab still prospering in the digital era – was key to working out those methodologies. “We’d take it as far along in the DI as possible, then scan out to film and match it back,” Cole adds. “The negative was not a printing stock. It was a nonprintable digital negative, optimized for this specific process, and used as a data storage device. Scanning it back in afterward used scientific procedural processes to bring the image back into ARRI’s Log-C world. I had to employ the same lookup tables used for the creative DI. This also accounts for all the film quirks, and matches that procedurally; and I’d do a trim pass after that, just for a final polish, the last two percent.”

In addition to at least one follow-up feature, Villeneuve has a spinoff TV series being developed based on other Herbert material, and Vermette is already enthusiastically developing concepts for Dune, Part 2, which will include the material covered in Herbert’s first novel. “The book was just so prescient and so accurate in presenting questions we now face every day in this century,” Vermette states. “Good sci-fi resonates because it is about us. If we want to have a better world tomorrow, we had better keep thinking about these aspects. Dune isn’t just a coming-of-age story; it’s for people everywhere who want to deal with these world-changing events.”

Dune – Local 600 Camera Team

Director of Photography: Greig Fraser, ASC

2nd Unit Director of Photography: Katelin Arizmendi

Aerial Director of Photography: Dylan Goss

K1 Technician: Eric Dvorsky

Still Photographer: Chiabella James