A Single Frame. By Pauline Rogers. All Images from A Single Frame / Courtesy of SMPSP. Main Image: Colin Firth during a break while shooting The Single Man in South Pasadena, CA (2009) / Photo by Melissa Moseley.

It’s their third book and it’s big, bold and beautiful, as it should be. This hard-cover coffee-table volume, celebrating the 20th Anniversary of the non-profit Society of Motion Picture Still Photographers (SMPSP), shows the enormous talent and creativity it takes to capture that “magic still frame” that may very well become the global face of a cinema or television franchise.

“Creating a single image that evokes the spirit of a two-hour movie from more than 170,000 frames is a daunting challenge,” shares John Bailey, ASC, in his introductory essay for A Single Frame. “Motion picture still photographers embrace that challenge. In fact, the movie we viewers imagine in our mind’s eye is often of a photograph that’s not even in the movie. Many of the most recognizable photographs of movie stars, still in costume for their roles, are created off set, sometimes in elaborate staged environments crated by movie still photographers.”

Bailey goes on to write how “barren our sense of film history would be without the dedicated work of these men and women who, even between setups, and while the rest of the crew is standing around waiting for the actors to appear on set, are always looking for that revealing moment, a gesture or a fleeting exchange that might yield deeper insight to the filmmaking process.”

One can only wonder how the book’s committee of unit photographers – Suzanne Hanover, Melissa Moseley, Nicola Goode, Martha Winterhalter and Phil Bray – made their selections. They culled through five entries from each member to make A Single Frame a reluctant page-turner. And the book begs readers to take their time, drinking in film history with each passing page. The committee’s mission was to find images that might not have made the cut for Hollywood’s publicity machine, or were never intended for mass consumption, but said something to each photographer.

Hanover says that “part of the fun” was putting photos next to each other to see how they looked together. They found images that had a sense of humor in David Strick’s plate from Deck the Halls that broke the fourth wall by including crewmembers – reality versus unreality. And they found iconic images, like Ralph Nelson’s photo of Sharon Stone from Basic Instinct or Peter Sorel’s Dick Tracy.

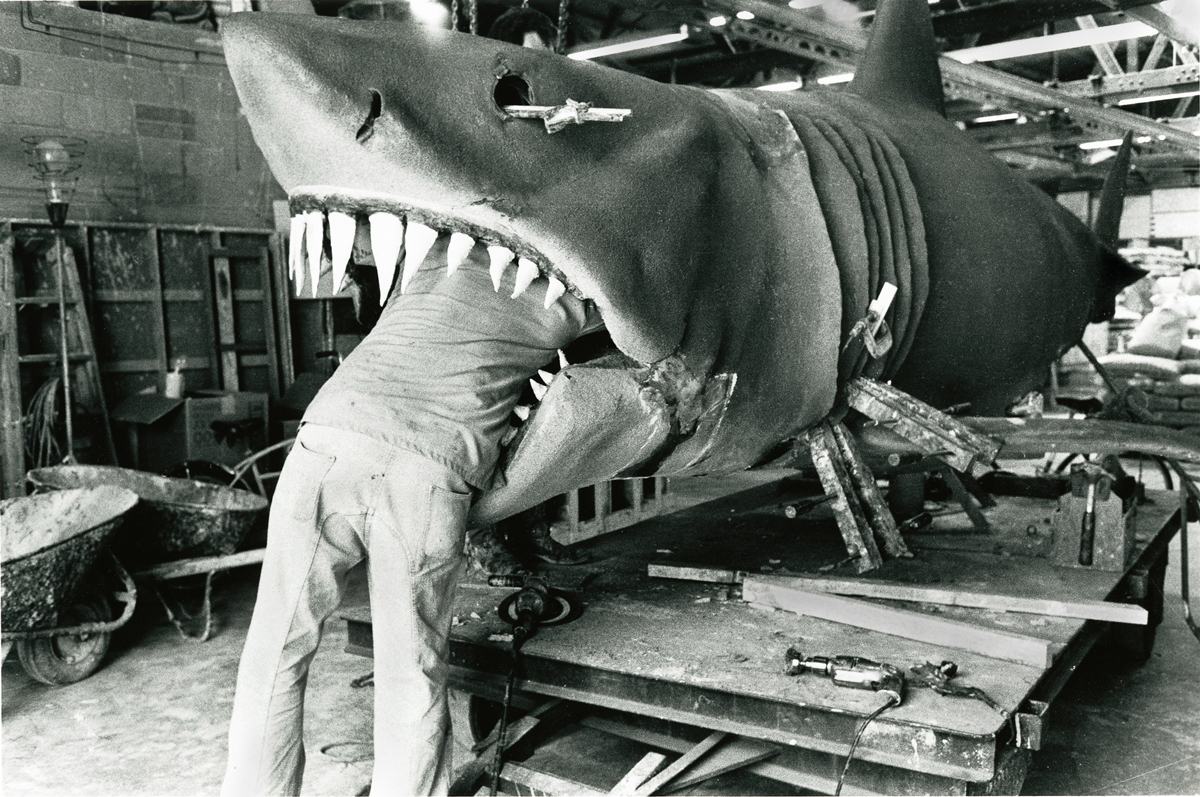

Readers who weren’t around Hollywood in the 1960’s and 70’s will likely linger on images of stars like Gene Kelly, Fred Astaire and Liza Minnelli casually strolling across the MGM lot in 1974 (Wynn Hammer), or the iconic publicity still of Dustin Hoffman and Anne Bancroft from The Graduate (1967), shot by Bob Willoughby. Then there is the mixture of past and present that Melissa Moseley caught in 2008 – an image of Colin Firth, taking a break from shooting A Single Man, as he walks in front of a Psycho mural. Or the behind-the-scenes moments – like Anthony Friedkin’s surreal construction shop photograph of “Bruce” from Jaws, circa 1978.

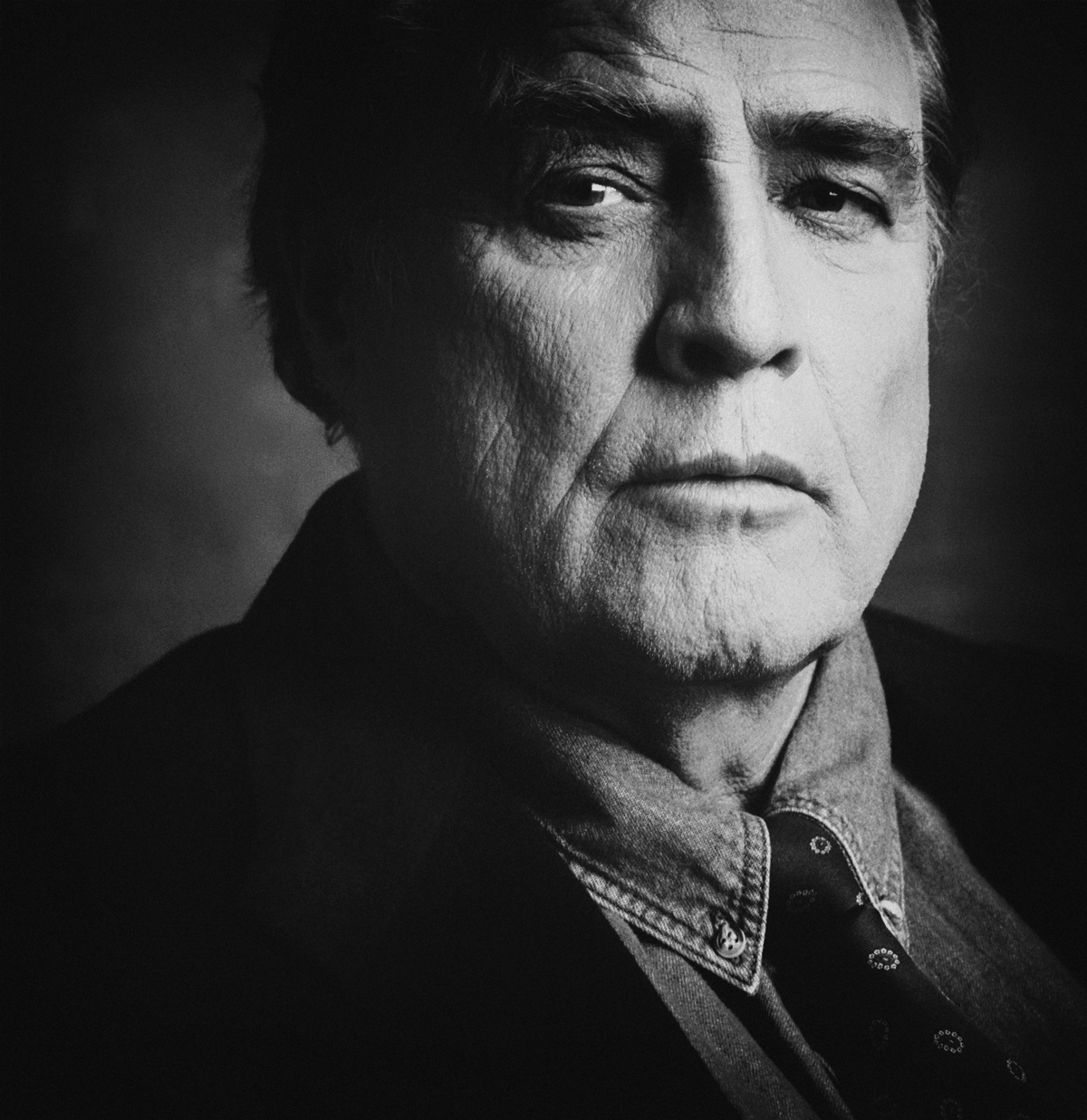

It was a labor of love for the Guild photographers who submitted images. Merrick Morton wanted to show the people who made things happen behind the scenes in one-on-one relationships with the subjects, and his image of Brando says it all.

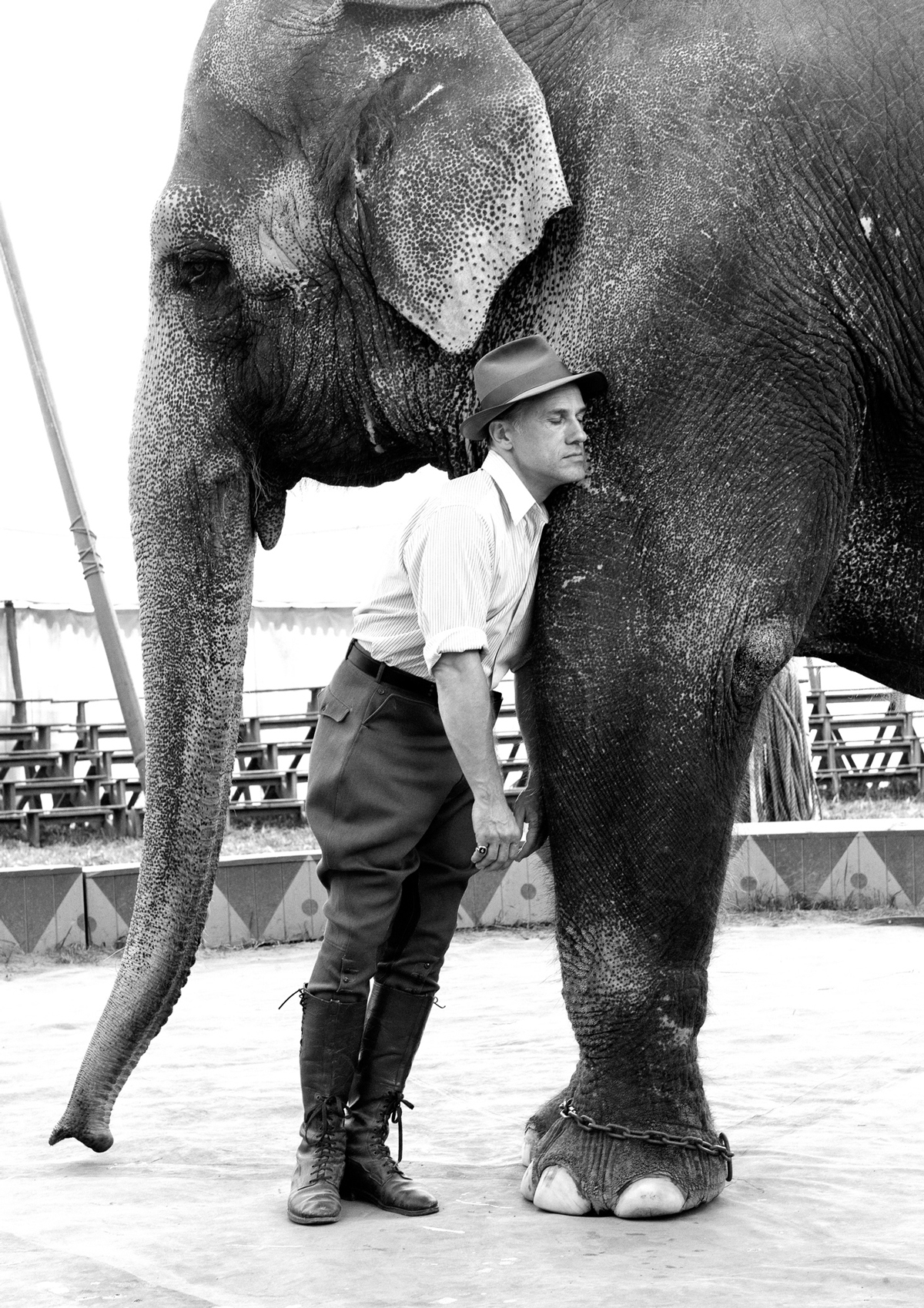

David James, on the other hand, chose a chance moment for which photographers aren’t often looking but are grateful for finding, like Christoph Waltz with the pachyderm from Water For Elephants. James remembers telling Waltz: “Don’t stroke her, lean against her,” and Waltz did, creating a once-in-a-lifetime moment for star and shooter.

In the book’s Forward, Wes Craven quotes Vladimir Horowitz. “Playing the piano is a combination of brain, heart and means. All three must be even. If one falls short of the others, the music suffers. Without brains, you are a fiasco. Without means, you are an amateur. Without heart you are a machine. It has its dangers, this occupation.”

Craven describes the “brains, heart and technique, all in balance,” that comprise the set photographer’s craft. “Get great shots, and all the while remain invisible. No small feat,” he writes.

Likewise, this book was no small feat. ICG congratulates SMPSP members (all of whom are also Guild members) for providing a window into that balance and creativity that make the unit photographer so vital to this industry. Keep working on archival preservation of historically and culturally important stills. Keep serving as a forum for exchanging ideas and the ever-changing issues facing still photographers today. And, please, put together another book to showcase even more of this time-honored film craft.