The impact of Sol Negrin, ASC, SOC, on the film and television industry will live on long after his passing, as his peers, colleagues, friends, family and students recall in this loving tribute.

By Pauline Rogers

It was 1976. The second unit on John Guillermin’s King Kong starring Jeff Bridges and Jessica Lange was working on Kong’s fall off the Twin Towers. Kong was lying on the ground. “But, someone had stolen one of Kong’s eyeballs,” recalls AC John McCarthy. “Production said there wasn’t a replacement. They were freaking out and didn’t know what to do. Not a problem for Sol Negrin. He suggested painting a 10K or 20K bulb to match the other eye, and put it back into Kong’s head. That’s what they did, and it made the picture.”

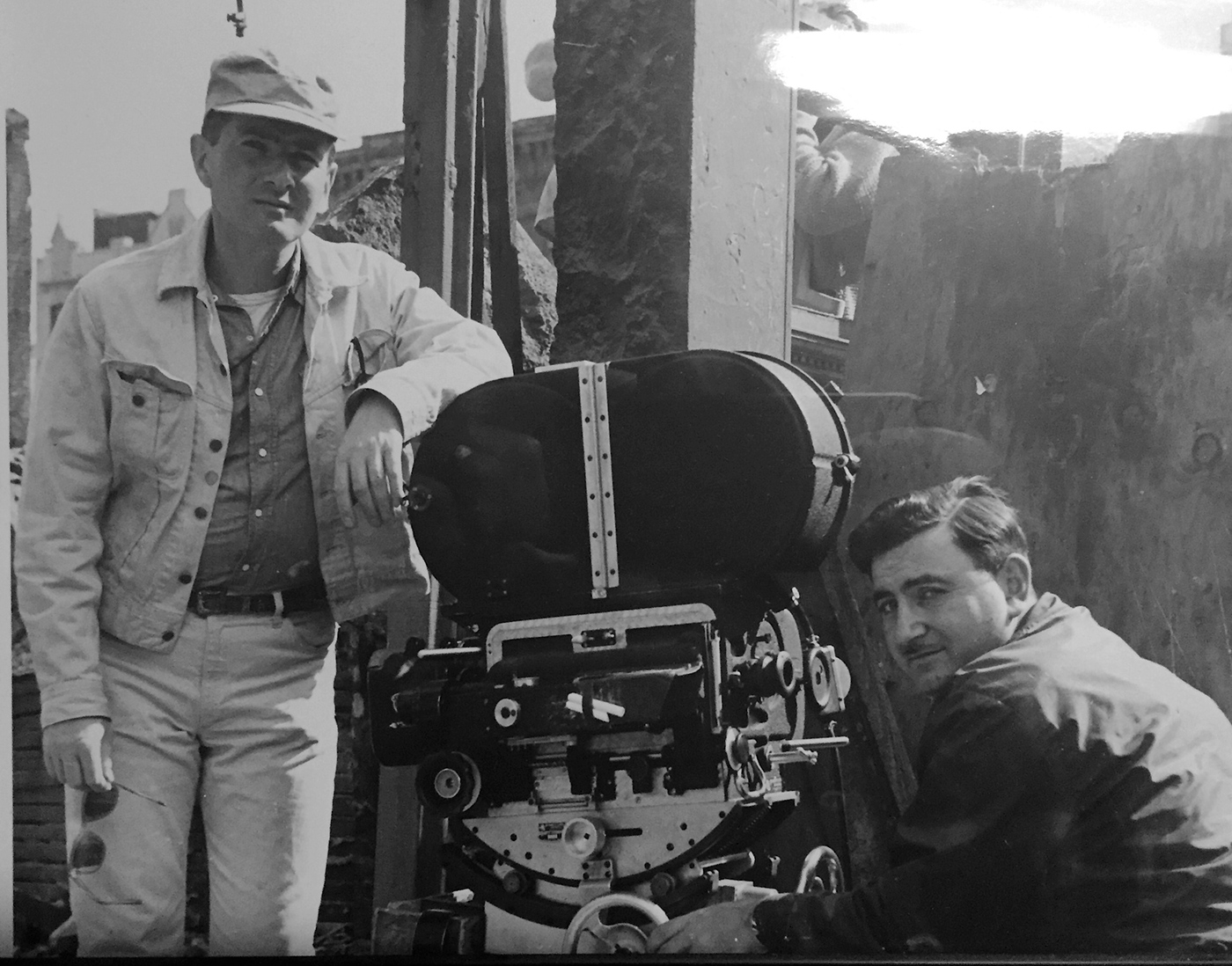

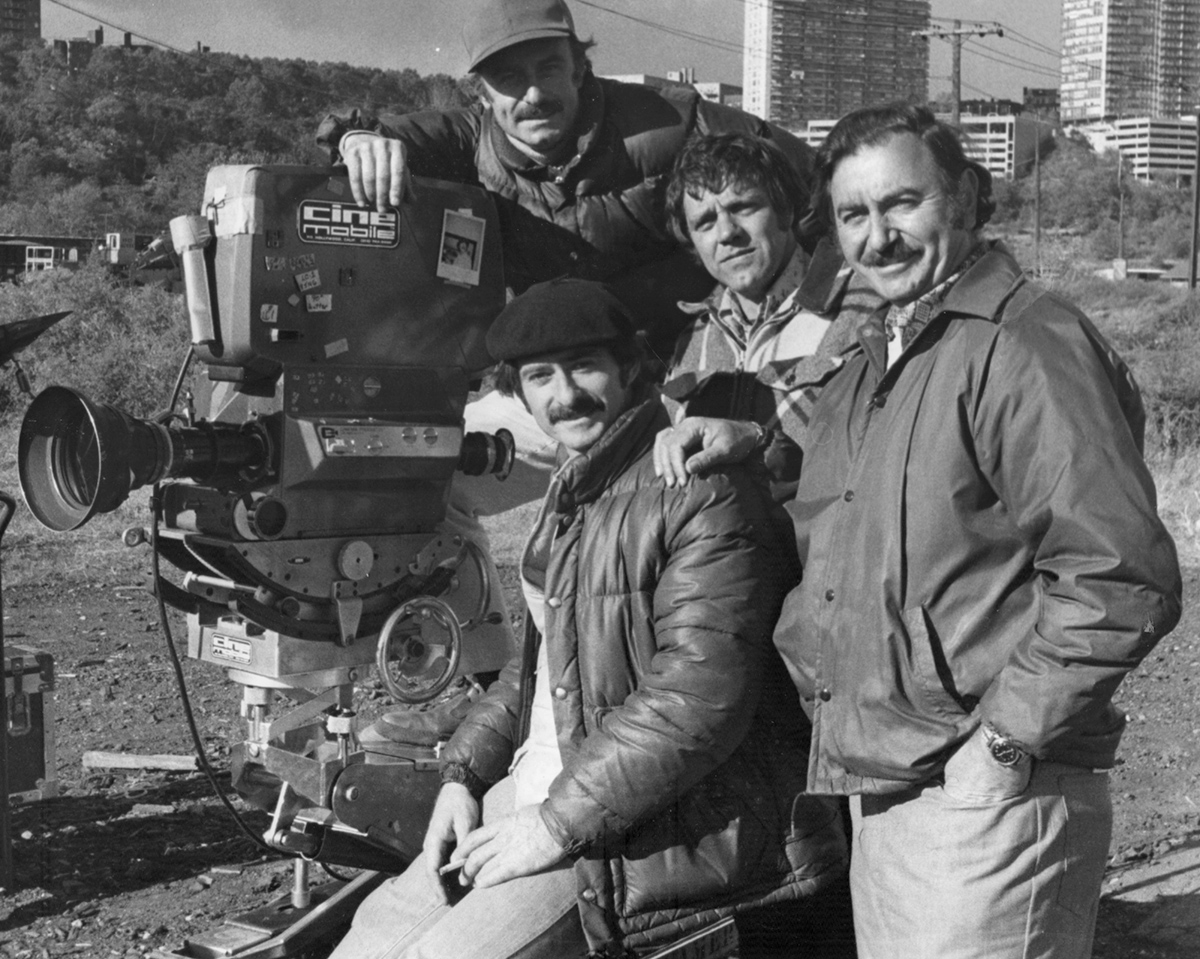

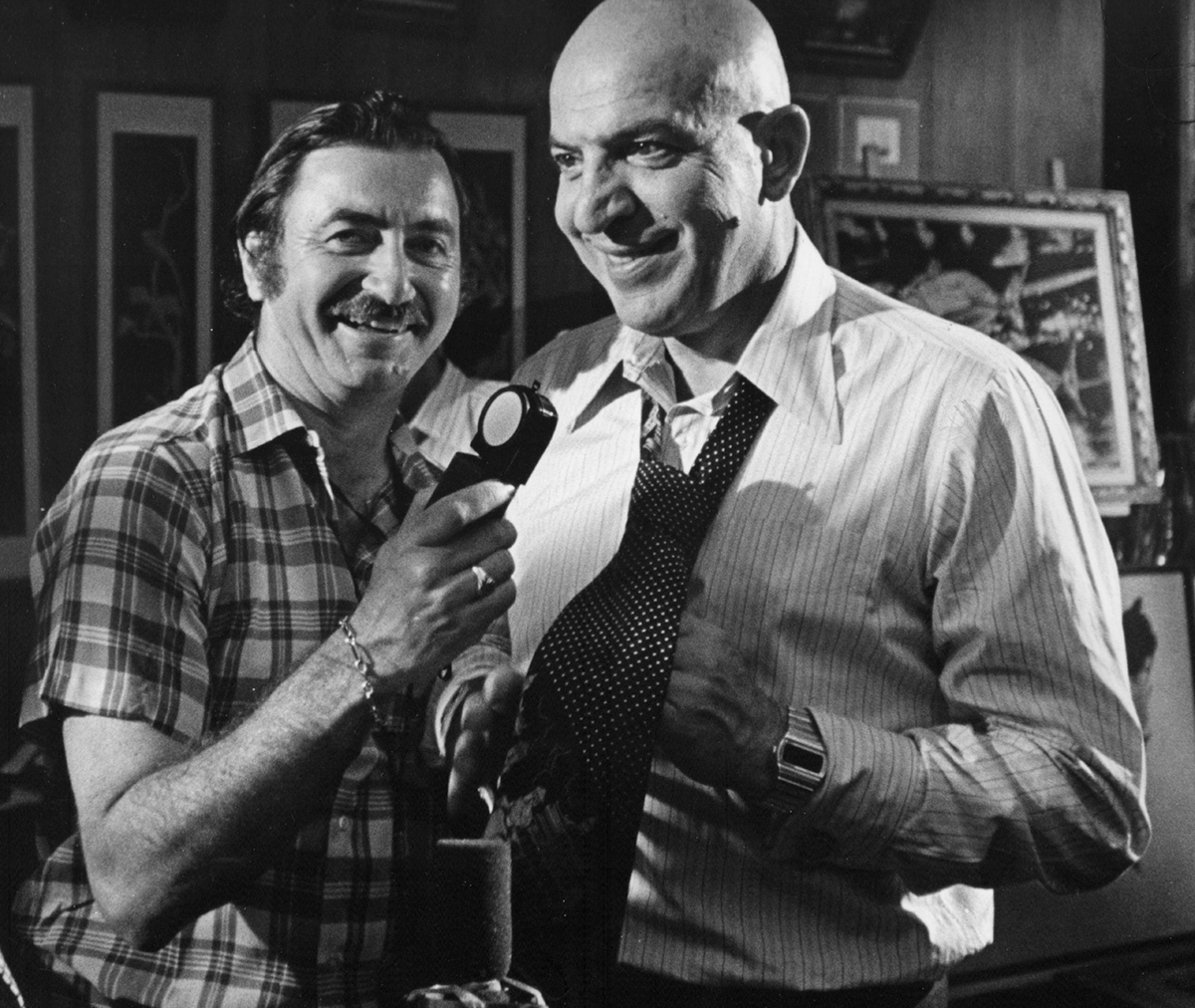

When remembering Sol Negrin, ASC, SOC, who passed away March 20, 2017, there is much to celebrate on the professional side: five Emmy nominations, including Kojak (1974, 1975, and 1976), the telefilm The Lost Tenant (1978) and an episode of Baker’s Dozen (1982); four Clio Awards, one for American Tourister’s memorable “Bouncing Suitcase” campaign in the 1970s. There was also his work on a range of classic TV shows and features – McCloud, The White Shadow, Rhoda, The Patty Duke Show, Superman, Coming to America, Jaws 2 and RoboCop among them. That’s the work – and there was plenty of it.

But there is also Negrin’s personal integrity and character, which encompassed his undying determination to educate – properly – those wanting to become part of the world he loved. Stories like his creative problem solving on King Kong have become timeless memories of the many people Negrin touched.

Cinematographer Patrick Cady, ASC, for example, met Negrin when the latter was a teacher at NYU Grad Film School. He says that while he learned “some pretty cool technical stuff” from Negrin, “Sol also became a true mentor for me – answering all my weird questions with kindness and patience. He championed my second feature, Girlfight, wanting to screen it for Local 600 before I was even a member. He screened Sunshine State – a movie that introduced me to the power of Local 600 – and Sol’s commitment to supporting it. After the screening, I remember going to brunch with him and meeting Geoffrey Erb [ASC] and Dejan Georgevich [ASC].”

And, Cady adds, Negrin’s presence seemed to be everywhere.

“When I was shooting my first series, Cold Case, in L.A.,” Cady continues, “we found a little plastic action figure that, to me (and to those who knew him) looked like Sol. We decided to hide the figure in shots if we could. The set dresser got onboard, and for the second half of that first season, Sol Negrin was a constant presence!”

In fact, it was while Cady was shooting Cold Case that Negrin called Cady on the set to say he’d written a letter to the ASC to recommend Cady for membership. “I thought it was way too early in my career,” the DP remembers. “I said I needed 10 more years of experience. But, I learned that if Sol was a fan – if he took you under his wing – or was excited by your work – you had a cheerleader for life. It took a second letter – at a different time – but because of Sol’s determination, I got in!”

If Sol Negrin couldn’t reach you in person, there were always those famous phone calls. One made to Stefan Czapsky, ASC, was crucially important. “It was 1992, and the Tim Burton movie that I shot, Batman Returns, opened to mixed reviews,” Czpasky recalls. “I was disappointed that the mention of the photography [ranged from sparse to] sometimes negative. USA Today said it looked ‘like it was shot in an inkwell.’ I was feeling unnoticed and unappreciated.”

Czapsky recalls how the phone rang one Sunday evening, in his dark New York City apartment. “‘Hi. This is Sol Negrin,’ I hear a voice say on the other end. ‘I just saw your movie and thought the photography was fantastic. Really good blacks. What film stock did you use?’ I told him the slow film stock – 5248 ASA 100. ‘No kidding,’ was Sol’s reply. ‘Congratulations.’ I had been living in New York since 1993 and had difficulty finding work. To get a call from a New York City ‘elite’ like Sol meant so much, especially when he took ‘shot in an inkwell’ as a compliment.”

Some years later, Negrin sponsored Czapsky into the ASC. “I remain forever grateful for him for reaching out to an outsider. It means a lot to be complimented by your peers,” the DP says.

Connecting with strangers like Czapsky was just something Negrin did if he thought he could help. And, no matter what Negrin offered, that person came away knowing he had support and a new friend. “In 2006 I was contacted by an award-winning music-video director to do a Tupac Shakur shoot,” recalls Paolo Cascio. “I had never been to New York before and didn’t know the town. I immediately contacted my friend Michael Negrin. ‘You are going to have the best time,’ he told me. Then he gave me the best advice – that the light is going to constantly move on me.”

“Let me give you my dad’s number,” Negrin told Casio. “I made the call,” Casio says. “Sol was there for me immediately – not what you expect from someone of his stature. He spent 30 minutes talking about New York, giving me numbers of rental crews – and saying, ‘Just tell them Sol sent you,’” Casio recounts. “He gave me a tremendous amount of confidence to move forward. This 21-day shoot in New York hit seven film festivals. When I saw Sol in person at the ASC, he had a big, beautiful Sol Negrin smile – and a ‘good for you!’”

That positive reinforcement also included vendors whom Negrin could convince to help those students he championed. In film school, Negrin was the person everyone looked up to. “It was early into my college career, when I realized how amazing it was to have someone like Sol Negrin teaching advanced lighting every day,” recalls AC Charlie Foerschner. “He saw the potential in certain students and went out of his way to help everyone, giving them every resource that was possible to complete their projects.”

Foerschner remembers how he wanted to shoot his senior thesis on film, “but I definitely did not have the money to buy and develop film – what people were doing at the time was shooting with HD cameras, which was the cheaper route,” he states. “Sol got us thousands and thousands of feet of film from Kodak New York, free. And, when it was ready to be developed, he sent it over to Technicolor – no charge! Once our film was completed, Sol was so proud of us, he played our movie to a group of Local 600 members at the monthly screening in Tribeca.”

Negrin was there for anyone who wanted to be part of the industry – and his beloved union family, Local 600. He was calm, authoritative, and knowledgeable on and off the set, but he also knew how to keep things light. “When I first expressed interest in the business as a kid, my dad emphasized that the best way to learn cinematography was through understanding basic photography,” recalls his son, Michael [ASC]. “It was an important lesson – but so was maintaining a sense of humor and fun while still getting the work done.”

The younger Negrin remembers his father’s often goofy impressions. “Instead of asking the dolly grip to boom up for a shot, he would sound like a German U-boat commander and yell, ‘Up shcope (up scope)! Load torpedo tubes von and two!” he shares. “When he needed electricity to pump the dolly, he – being Jewish – could get away with lines like, ‘I need Jews (“juice”) for za dolly, and if you don’t have any Jews, get me some gentiles.’ Silly stuff like that.

“When [my dad was] operating a camera, a director might ask him if the shot worked well and was sharp,” Negrin adds. “My dad would look up at him with one crossed eye and a very foolish smile and say it was fantastic. That always broke any tension there might be on a tough day.”

Long-time operator Maurice “Mo” Brown remembers how Negrin took as well as he gave, partially because of his natural sense of goodness and gullibility. Both Brown and DP Lou Barlia, SOC, recall the infamous “turkey day.” It was on the set of Kojak, when the gaffer came in one day and asked if the crew had gotten their turkey for Thanksgiving.

“Before the Teamsters had got them,” recalls Brown. “I knew that the ‘turkey’ thing was fictitious – but we all played along. Sol got pissed. When the production manager walked through the set, Sol practically accosted him. ‘Where are our turkeys?’ Caught in the gag, the production manager said he’d see what he could do. Of course, no turkeys appeared!”

“A month later, we pulled the same thing on Sol again,” Brown adds. “This time it was show jackets. ‘This production company is cheap not to get jackets,’ someone said. Lo and behold, Sol championed up, and everyone ordered jackets. Three days later, when they were ‘supposed to be delivered,’ he sent an assistant to get them. The answer – ‘the Teamsters got everything.’ Sol wasn’t too happy with the production manager.”

There was also one sweltering New York day when Negrin decided to buy the camera crew ice cream. Brown’s assistant asked how many. “‘Eight,’ is what Sol called,” Brown remembers. “I was concentrating on something else. ‘You want me at an eight?’ I called. Without missing a beat, Sol yelled, ‘No, eight ice creams. You’re on a 5.6.’”

Crewmembers also say Negrin was never intimidated. “I remember a big commercial shoot for High Point coffee featuring Lauren Bacall,” Brown continues. “The production was nervous, because she was a challenge to work with. The first day on the set, she came up to Sol with a look, like, ‘Make sure you make me look good.’ Without batting an eye, he turned to her and said, ‘For you, I will shoot through linoleum.’ No one believed he said that to Lauren Bacall. The next day, however, after dailies, she came over to Sol and gave him a hug.”

ICG, ASC members, students and former students report there were enough such “Sol-isms” to fill a book. But Michael Negrin remembers his father’s memorial service and funeral, and how many friends, colleagues and students showed up. “It simply overwhelmed my family,” he shares. “This outpouring of love and admiration not just for my dad’s dedication to the craft of cinematography but for his selfless determination to help people get a start and to guide them into the Guild, as well as all the new faces he brought into the ASC.

“I was so taken by the number of women cinematographers who expressed their gratitude for his desire for them to get a fair break in the industry,” he adds. “[New York-based Guild member] Reed Morano [ASC] in particular expressed in an email to me how far ahead of his time my dad was in regard to supporting women to get their fair chance to succeed.”

As Dejan Georgevich said at Negrin’s service: “He was a great man – a legendary cinematographer, trade unionist, beloved educator whose capacity for giving to others was always inspiring. He taught us all something about giving back to the next generation of motion-picture artists and technicians. He was forever helping others to be better craftsmen and craftswomen, as artists and as family. Role models of his kind are an influence for generations.”