Television’s most heart-pounding action comes from an obstacle-course road show, better known as (cue the announcer) American Ninja Warrior!

Anyone who’s been in the control room during a live sports broadcast – college or pro football, the March Madness basketball tournament, an MBL game – can sniff the air of professionalism that breathes through every monitor and camera angle, not unlike, I imagine, watching a group of flight controllers landing planes at a busy airport. But on my recent visit to Universal Studios, where the team from American Ninja Warrior (the feel-good reality competition show, where contestants are cheered no matter the outcome, and the only villains are the ever-changing physical obstacles they try to conquer) was working, I see every bit the level of professionalism of a Super Bowl control room, but also something else. Emotion.

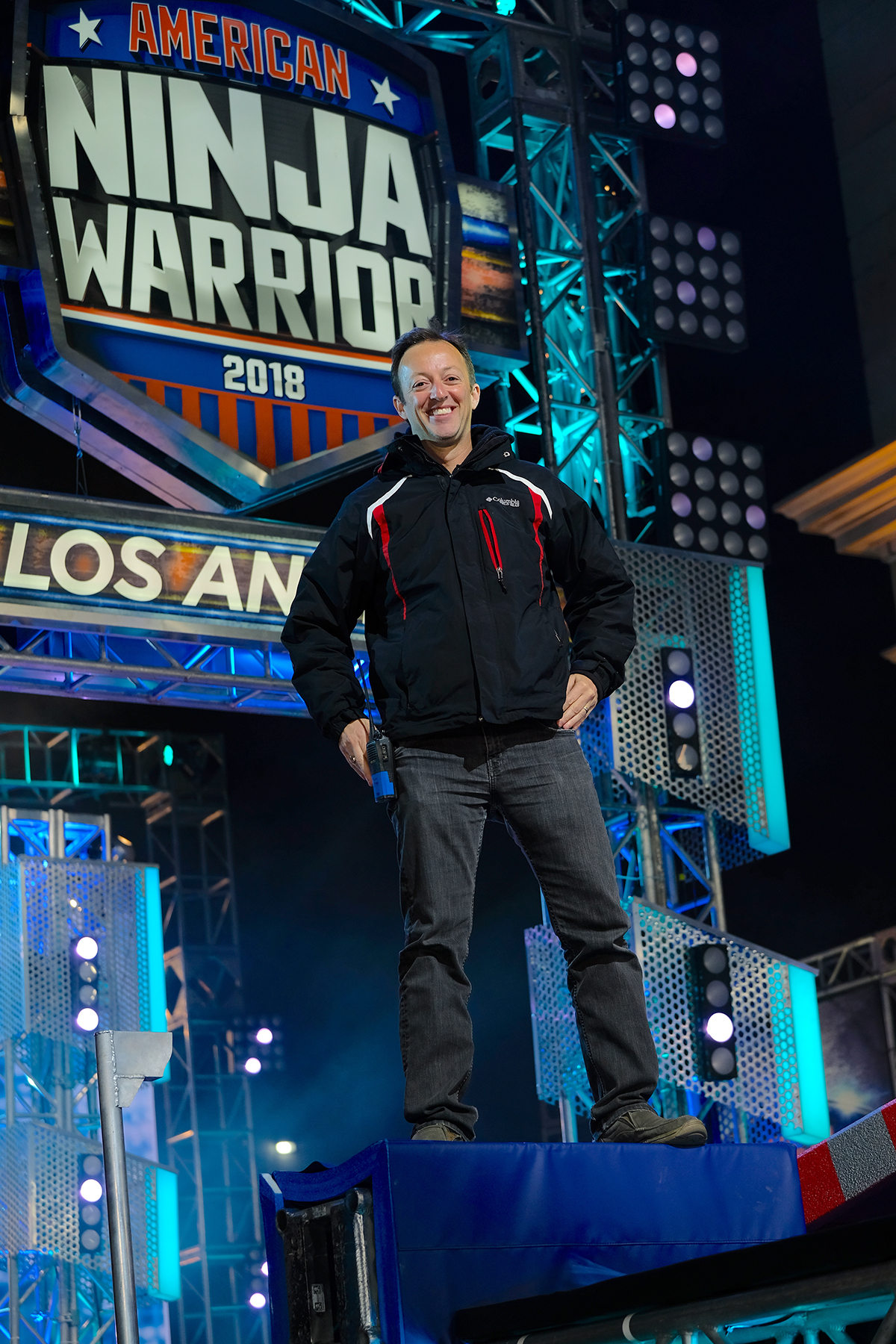

“Any time you have elements like a rooting interest in the contestants, a clock, dynamic personal stories, and friends and family watching from the stands, you’re going to have a control room where people get personally invested,” describes director Patrick McManus, who came aboard in Season 6 and has, according to the show’s longtime DP/Lighting Designer Adam Biggs, brought a new level of production value to Ninja Warrior.

McManus, whose résuméincludes NFL and NCAA football games and Indy Car racing,makes this comparison: “Baseball doesn’t get cooking until the 7thinning, and by the time you reach the 9thinning, everyone’s on their feet. Every time a Ninja starts the course, it’s the 9thinning! There’s no ramp-up to the drama,and you’re embedded. So when a walk-on gets up the warped wall, you’ll see high-fives around [the control room]. And that emotion carries through to everyone on the set. You can’t help but root for these people.”

The UK-born Biggs, whose broad skillset of documentary, scripted episodic and unscripted reality made him a perfect fit when Ninja co-creator Kent Weed (and the company he co-runs with Arthur Smith, A. Smith & Co.) transposed Japan’s popular Sasuke obstacle show to U.S. television, says he can’t help but root for his large IATSE camera crew and lighting team, who make Biggs “look great” every night.

“NBC’s goal for Ninja,” Biggs relates, in between asks through his com line to any of the 18 camera operators shooting the course, “was how will viewers know the difference between Season 10 and reruns? The answer was more production value, including a second warped wall with new lighting and graphics, another Technocrane, a Cablecam [that runs the length of the course from above] for the city finals, and drones to provide full aerial pullbacks. [At the National Finals, helicopters replace drones, which are not allowed in the Las Vegas airspace.] It’s really a testament to this camera team that as we continue to add more elaborate positions each season, they rise to the challenge without even so much as a hint of compromising safety. Ninja may well be the safest, most well-oiled machine I’ve ever seen.”

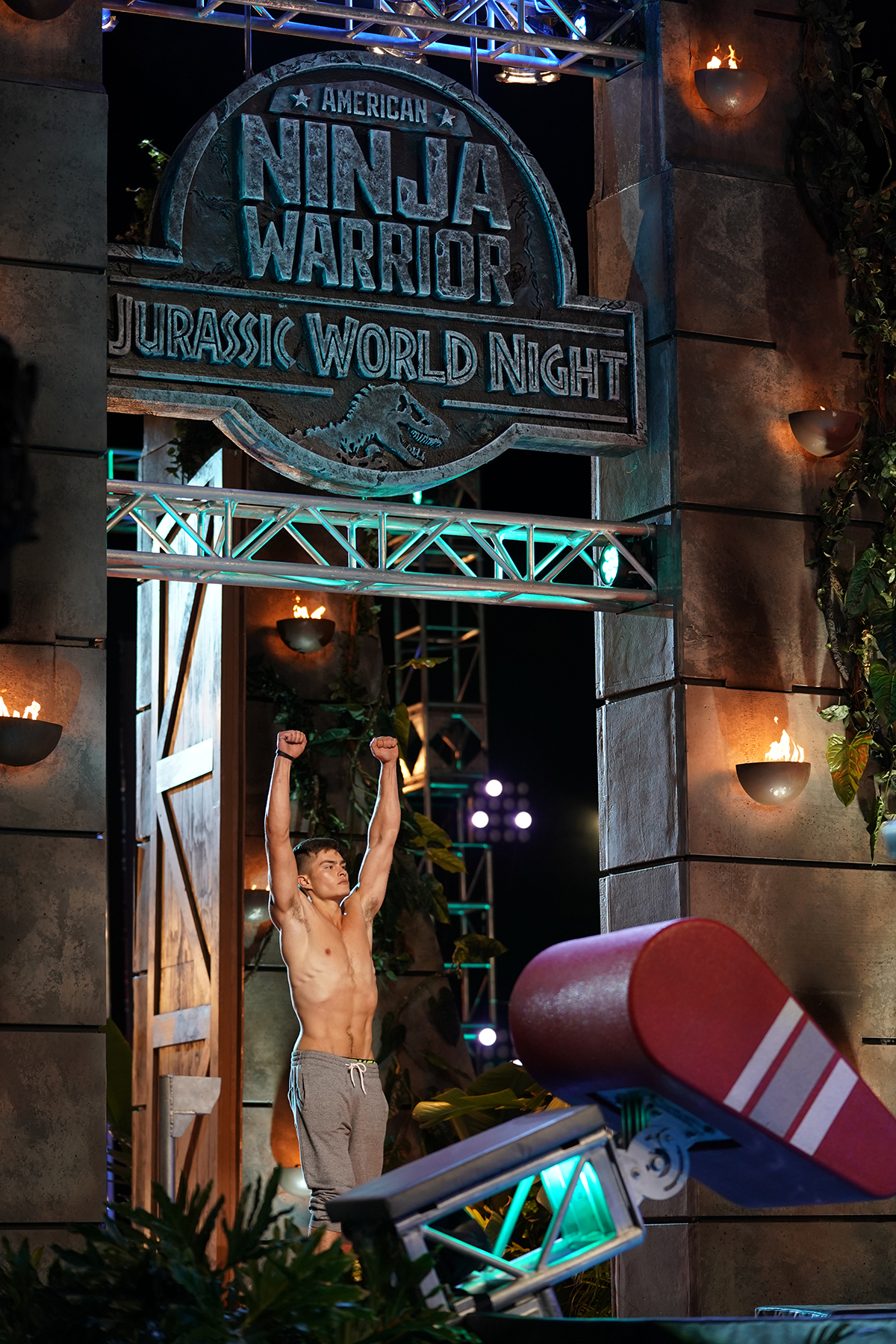

Well-oiled to be sure, but not without its fair share of challenges. The L.A. regional qualifier was spectacular even by Ninja’s epic standards. It featured a Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom promotional set, six months in the making, which had to be shot and struck in a 24-hour period. “For this Jurassic World integration,” Biggs continues, “we had basically two art departments – our regular Ninja look [set by Production Designer Michael Carney] and the special promo look [led by Production Designer Ryan Faught, who pre-visualized the Jurassic set in animatics, and Michael Levinson, who art-directed the final product]. That meant I needed completely separate lighting design and camera coverage for just one taping.”

Well-oiled to be sure, but not without its fair share of challenges. The L.A. regional qualifier was spectacular even by Ninja’s epic standards. It featured a Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom promotional set, six months in the making, which had to be shot and struck in a 24-hour period. “For this Jurassic World integration,” Biggs continues, “we had basically two art departments – our regular Ninja look [set by Production Designer Michael Carney] and the special promo look [led by Production Designer Ryan Faught, who pre-visualized the Jurassic set in animatics, and Michael Levinson, who art-directed the final product]. That meant I needed completely separate lighting design and camera coverage for just one taping.”

Biggs explains that less than 24 hours before I arrived, he was helping to place a 40-foot t-rexand pteranodon in a way that would work for lighting and cameras, as well creating lighting cues for the huge entrance gates with pyro that each Ninja walks through before starting the course. “Universal has a very specific color palette for the dinosaurs,” he details, “and that factored into how we lit the foreground and background elements, all of which were added for just one night.

“After we finish shooting tonight,” he adds, “we’ll have a daytime crew strike [the Jurassic set] and then reset for our regular show, which shoots tomorrow night! The host tower [where Matt Iseman and Akbar Gbaja-Biamila announce the show] had special lighting just for the Jurassic set. So working with [Gaffer] Jeff Noble and [Lighting Director] Ed Motts, we had to create those cues, as well as the programming for tomorrow night’s final. Also, this Jurassic tie-in night has 120 ninjas running the course, so we, literally, will finish just before the sun can rise and create havoc with the continuity and lighting.”

Talking with 45-foot-Technocrane Operator Jason Kay just after Jurassic World star Chris Pratt has shot a promo on the Ninja set reveals a host of new challenges for the night. “Normally we don’t have to worry about all this set dressing [shrubbery, palm fronds, etc.],” Kay points out. “So [the Jurassic integration] will alter how the cameras fly, and the route the handhelds would typically use to cover the runners, along with the operator shooting the friends-and-family side. The Grip Trix camera car [with Steadicam operator], which always parallels the course, will end up in a different spot as well. We normally duplicate all the different camera positions as we travel from city to city [where the regional finals are held prior to the National Finals in Las Vegas], but tonight is a whole different animal [laughs]. No pun intended.”

Kay, who’s starting his fourth season on Ninja, says bringing in multiple telescopic camera cranes [the 30-foot Techno is set near the parallel 14.5 and 18-foot warped walls, which contestants must climb up to complete their run] is rare for the world of unscripted reality shows. “I would normally not get a Techno call for unscripted,” Kay describes. “But there’s so much production value behind this show, and they keep adding more every year. Last season we had three Technos for the Vegas finals, including a 60-foot Moviebird. It’s always challenging because the space I have to work in is fairly tight and I cannot affect the course or runners in any way.”

All 18 Ninja camera operators have discrete assignments. “My Techno will do a big move-in as the Ninja comes through the Jurassic gates and the pyro goes off,” Kay continues. “Then as they count the Ninja down to start, I’ll do a big move-out. Because I don’t know how it will be put together in editorial, I try to change each move slightly – like using different foreground elements – while being careful not to affect the tight or slo-mo shots from the long-lens [Sony FS700, Sony HDC4300] cameras up on the platforms, or the handheld [Sony F-800 microwaved back to the control room] that sees the run in a wide shot. With so many operators all working in a tight configuration, there’s a different dynamic than a feature [or scripted TV]. Let’s just say the camera channel on our headsets gets a lot of use – we’re always talking to see what shots we can get without impeding lighting, each other, or the course!”

As Art Director Michael Levinson watches over his team finessing the set dressing after Pratt’s promo, Guild member Austin Rock steps off a Condor to tell me about his role as Ninja’s Head Utility. Rock oversees all of the POV cameras, as well as the SMPTE lines that feed the long-lens studio cameras raised up on the platforms. “We make sure all of the GoPros are set up, and basically anything video-related is rigged and working properly,” Rock describes. “We use five lock-off POV cameras mounted to truss, and six [truss-mounted] robotic cameras in the middle of the course that shoot tight and overhead shots. I’ve been on Ninja for seven years, and the growth in the amount of cameras has been tremendous. Back in the day everything was copper, but now we’re all fiber, which makes for a clean and easy feed back to engineering.”

Rock, who has used the same team of four [including himself] describes the overall Ninja operation as “turn-key,” including a level of trust and shorthand that can boast of no gear falls in his seven seasons. “Everything in the air is safety-mounted so that we’ve never had a camera come loose or impact the contestants or the crew in any way,” he continues. “I’ve been a utility [for Steadicam] in other live-event areas, like the Oscars and Emmys. But Ninja is my only show in the reality world. And this team is really tight.”

Dominck DeFrank, now in his sixth season as Lead AC, says his team of AC’s (James Martinez aka “JMart,” Jesse Martinez, Shelby Cipolla and Patrick Bellante) are required – like the Ninjas they chase after – to bring their A-game every night. “It’s a very fast-paced, leap-frog environment that keeps us constantly on the move,” DeFrank describes. “We are [literally] racing along side each competitor as they make their way down the course, sometimes up to 125 times a night for city qualifiers. I’ve always found multi-cam obstacle course shows very challenging; we watch each other’s backs, forever focused on keeping our ops and each other safe.”

The cohesion that envelops the entire Ninja set is no accident. The show is one of the most demanding and unique in the industry, as it requires a multitude of complementary skillsets to fulfill its hybrid format – equal parts live sports, live event, and personality-driven storytelling. Nowhere is that blend more evident than amongst Ninjas’ operators. Co-Executive Producer Kristen Stabile says many are handpicked for their experience.

The cohesion that envelops the entire Ninja set is no accident. The show is one of the most demanding and unique in the industry, as it requires a multitude of complementary skillsets to fulfill its hybrid format – equal parts live sports, live event, and personality-driven storytelling. Nowhere is that blend more evident than amongst Ninjas’ operators. Co-Executive Producer Kristen Stabile says many are handpicked for their experience.

“Ninja is unique in that we have handheld reality shooters [covering the Ninjas on the course, the friends and family, and post-run Ninja interviews] along with experienced long-lens sports camera people, who are very skilled at following action at varying rates of speed,” Stabile tells me. Biggs says sports shooters are a different breed than “operators who do reality or handheld follow-docs, because they have to anticipate where the action is headed. It’s a different technique – focus, zoom, panning, etcetera – when you’re on a long-lens broadcast camera versus having a camera on your shoulder. The reality operator, on the other hand, is usually very adept at single, handheld coverage, and knowing how to discretely follow a conversation on set, often on a wide lens. Both skillsets are invaluable on Ninja Warrior.”

“Since [Patrick McManus] comes from broadcast sports,” Stabile explains, “he has a shorthand with those long-lens operators, who are skilled at shooting the Ninjas who move very quickly through the course. They are great at capturing that hand or finger as it slips off a bar, or holding focus in frame as the athletes are literally flying through the air.”

McManus says operators that are experienced with “sports-lens cameras” are used to shooting athletes moving quickly at distance [like on a football field]. “On this show, they need to hold focus under dark conditions, and face other similar challenges,” he observes. “Handheld operators need to be strong and durable, and have framing skills that include catching background and foreground elements of the various cities we travel to, while always keeping sight of the objective, which is to reveal all of that emotion during the Ninja’s run.”

While the director admits different operators have different strengths, he says it’s Ninja’s camera team’s ability to operate multi-camera positions that is most beneficial to his show call. “With the exception of a Techno or a Fly Cam, most everyone can do hard cameras well as RF handhelds, which is key if someone twists an ankle and we’re down a position,” McManus adds.

“We have operators on this show who can carry 50 pounds of camera on their shoulders, no problem. It’s a smart and savvy crew, meaning they keep track of each other’s shots. If two operators are standing next to each other, they know I want one shooting tight, hands and face, and the other head to toe showing the whole obstacle. It’s that perfect mix of hard cameras that capture emotions, faces, handgrips on the obstacles, and those handhelds who can move dynamically with the Ninja on the course so we see the connection with the audience.”

Megan Drew, who was on a long-lensed platform camera (shooting high-speed frames for close-ups and slow-motion replays) for the Jurassic night shoot, is a prime example of Ninja’s skill diversity. “My background is mostly unscripted,” she explains. “But I’ve been asked to work every camera and support setup out there, short of swinging a jib! For the hard cameras, we usually shoot at a 3.4 stop, at the long end of a 95×lens. When a super Ninja is racing straight toward you at speed, and you have no time to look with the naked eye to see where the athlete is geographically, you have to be super sharp and dialed-in to make sure you get the necessary moments focused and clean. It’s a constant challenge on every run, and one I love.”

Drew also loves the magical moments Ninja provides. “My first season on the show,” she continues, “I got to shoot Kacy Catanzaro as she became the first woman to make it up the Warped Wall. Getting the hero shot as Kacy celebrated provided a sense of pride that I was a part of a groundbreaking moment. The unique thing aboutNinja is that Patrick brings his best crew from sports to mix with his new stable of unscripted operatorsand crew.We all have different working stylesand habits, and it’s fun and interesting to compare notes.”

McManus says every Ninja show includes foreground and background elements, along with overhead, side angles, close-up, slo-mo, etc. “It’s often the personality-driven aspect of the series that drives the coverage,” he describes. “The big difference between Ninjaand more traditional broadcast sports is that when you walk into the Superdomeor the Indy 500, everything’s done – you’re not thinking about lighting, set design, or decorative elements. On a Ninja set, we look at every possible angle – not to show sky but to show background, not to show shadow but to reveal faces in the crowd or a key part of an obstacle that’s tripping everyone up. And it falls on Adam to bring all those elements together with lighting and camera placement.”

Many consider “Biggsy,” as he’s known around theset, the connective tissue that links Ninja’s hybrid elements. Drew says she’s continually impressed by Biggs’ lighting, “which keeps getting more nuanced and sophisticated, even though he has the impossible job of lighting a several-hundred-yard course over multiple obstacles and rest areas,” she adds, “with cameras on the ground, on process vehicles, on jibs, on tower platforms and in the air on wires, not to mention in-the-moment interviews and audience reactions, as well as success and fail cues, all on a different location every two weeks, six times per season – without visible shadows!”

Many consider “Biggsy,” as he’s known around theset, the connective tissue that links Ninja’s hybrid elements. Drew says she’s continually impressed by Biggs’ lighting, “which keeps getting more nuanced and sophisticated, even though he has the impossible job of lighting a several-hundred-yard course over multiple obstacles and rest areas,” she adds, “with cameras on the ground, on process vehicles, on jibs, on tower platforms and in the air on wires, not to mention in-the-moment interviews and audience reactions, as well as success and fail cues, all on a different location every two weeks, six times per season – without visible shadows!”

Weed first hired Biggs as his lighting designer on The Swan (2004), which Weed directed. “I basically fell in love with Adam’s whole approach,” the EP admits. “Like me, he has a very diverse background – live event, variety, and reality – and his flexibility onset is fantastic.”

While Weed says he’s worked with many Emmy-winning LD’s (Guild members Oscar Dominguez and Kieran Healy being the two most celebrated), he’s continued to hire Biggs, because he thinks just like a director. “Adam’s more like an old-school film DP,” Weed adds. “He not only understands lighting for television, which all LD’s do, but he also has a broad knowledge of cameras and lenses, and those abilities really make him a director’s friend. Adam was there when Ninja first started in daytime [on the now defunct G4 cable channel], and he’s been essential to all the growth we’ve seen, in this our tenthseason.”

While all of what Weed describes is true, it’s Biggs’ overriding concern for the safety of his crew that shines through on the night I visit. Standing near the newly added 18-foot warped wall, which is inset on both sides with lighting patterns and colors Biggs designed, he explains how Ninja’s growth has been great fun, but not at the expense of safety.

“We have four shock blocks to protect us from electricity concerns with all of the many moving and fixed lights rigged throughout the course,” he gestures. “And those long-lensed hard cameras you see, which are 12 to 15 feet up in the air, are, of course, all safety-railed. They used to be up on scaffolding, but now it’s all truss platforms, which are more secure. In past seasons, we used operators harnessed in Condors for high shots, but we’ve replaced that with Cablecam, for similar safety concerns. Of course, no one ever climbs up on a platform without a harness on this show…except me,” he laughs. “I’ve been known to jump up with my meter, after we’ve pre-lit, to make sure the levels are correct. Bad Adam!”

Biggs’ self-assessment may be harsh, but his praise for his camera team (and how they execute McManus’ call) is all-out. “We have 18 cameras, but not on every obstacle,” he explains. “That means an operator covering obstacle one will [literally] run full speed down the course to get to, say, obstacle four; each camera will have two or three positions to cover in the first half of the course.”

The key to Ninja’s appeal, Biggs feels, is audiences grasping the various Ninjas’ individual challenges (and each one different), conveyed by each camera’s unique assignment – the wide shot for geography, the close shots and POV’s for the eyes, hands, and feet. “The ‘friends and family’ camera is incredibly important,” he says walking back to the control room. “There may be a half-dozen people all yelling, ‘Beat that wall! Beat that wall!’ And there’s only one operator in that right spot, with only one chance to get their reactions. It’s absolutely crucial to the story.”

As is the line cut McManus delivers each night after exiting the control room. While footage like the Ninjas’ “hometown stories” (shot by Guild operator Brian Connolly in a style consistent with Biggs’ look for each city qualifier and final) will be added in editorial, the veteran director says his line cut is often for the benefit of Iseman and Gbaja-Biamila, whose voice-overs are key to the narrative. “Those guys come up with brilliant lines reacting to [the camera angles] that show all of the personal connections,” he concludes. “Last season we had a female Ninja whose son did back flips every time she ran the course. Of course we need to include that in my line cut, no matter what [the producers] end up keeping in post.”

As midnight approaches, the Jurassic night has produced few keeper runs, much to the dismay of Ninja’s control room. With two preteens in tow, my night is over; but with some 90 more Ninjas yet to run, Biggs, McManus and company will strafe close to their sunrise deadline. Just after the DP whispers into his com line for more flare off a fixed camera, the room erupts in laughter – a walk-on named “Chivo the Goat” has raced through the first few obstacles, then paused to blow a kiss to “Camera 10” on the friends and family side. Moments later, when a prominent Ninja goes out much earlier than expected, groans of disappointment engulf the crowded trailer, and 1200 lights that encircle the course all go simultaneously red.

“That’s a single button the board operator pushes when a Ninja falls,” Biggs nods.

“I want that raptor to sneak up and scare him,” McManus tells an operator as the pyro pops and the next Ninja moves through the big Jurassic World starting gate. “That’ll be good!”

by David Geffner

photos by Tyler Golden/NBC Universal

LOCAL 600 CREW LIST

American Ninja Warrior

Director of Photography/Lighting Designer

Adam Biggs

Lighting Director

Ed Motts

Camera Operators

Derk Anderko

Jay Mack Arnette

Tim Baker

Cameron Cannon

Brian Connolly

Megan Drew

Malkuth Frahm

Brian Freesh, SOC

Jason Hafer, SOC

Will Hooke

Jeff Rhoads

Rodrigo Rodrigues

Brett Smith

Jed Udall

David West

Danny Whiteneck

Brenda Zuniga, SOC

Technocrane Operators

Steve Ritchie

Adam Vessels

Technocrane Technicians

Michael Fletchall

Jason Kay

Drone Crew

Mike Fortin

Mike Solomon

Falcon Operator

Darren Sanders

Falcon Pilot: Eric Foster

Camera Assistants

Patrick Bellante

Shelby Cipolla

Dominic DeFrank

James Martinez

Jesse Martinez

Loader

Lorie Moulton

Head Utility

Austin Rock

Utilities

Tim Farmer

Ryan Jordan

Video Controller

Alan Pineda

Still Photographer

Tyler Golden