Sundance indie David Lanzenberg leaps forward in size and budget for the time-travel drama The Age of Adaline. By Kevin H. Martin. Unit Photography by Diyah Pera / Frame Grab Courtesy of Lionsgate Pictures.

In The Age of Adaline, beautiful Adaline Bowman (Blake Lively) has led her life out of the limelight. This deliberate decision arises out of a need for secrecy regarding her unusual condition – Adaline stopped aging after a freakish car accident at age 29. But as the saying goes, time is the great equalizer; after being swept up in a grand romance, Adaline re-encounters a suitor from decades past, and complications ensue.

Lakeshore Entertainment spent years developing the property with different leads and directors before Lively and Lee Toland Krieger signed on. “I was intrigued by the theme of ageless beauty and the consequences,” Krieger recalls. “It becomes a kind of curse, and ultimately she sees the beauty in growing old. Given how obsessed our culture is with youth and vanity, it seemed a good subject. The trick was to treat the fantasy aspect as Big had done, as just one element, with the rest played straight and totally grounded.”

Krieger, a USC Film School graduate and lifelong cinephile, pondered the visual aspects that define films made in each of the eras in which Adaline’s story was set.

Essential to Krieger’s visual quest was Guild cinematographer David Lanzenberg, who first met the director in 2011. “I had worked my way up from being a loader and first AC to DP on videos and commercials,” Lanzenberg recalls, “and Lee contacted me on the basis of one he’d seen. He loves moving the camera in a kind of dance with the onscreen action, and so do I. Sometimes my ideas are too out there, and he brings me back to reality.”

The pair’s critically acclaimed indie feature, Celeste & Jessie Forever, premiered at Sundance a few years back, while more recently Lanzenberg lensed The Signal in New Mexico for cinematographer-turned-director William Eubank and Paper Towns with director Jake Schreier.

Adaline is a much bigger picture than either man had tackled, and Lakeshore offered an extended prep period. “We were the young, unproven guys,” admits Krieger, “so all that prep was a good way to indicate to them our approaches and intentions were valid, and we made a huge effort to solve nearly every issue well ahead of shooting. We are huge fans of Harris Savides, ASC, so we looked at The Game, which has a lot of the DNA we wanted, including the San Francisco location. Studying Fincher’s film, we found they didn’t do any conventional postcard coverage of the city, which is something we strove to avoid ourselves.”

Recent films like Rise of the Planet of the Apes, Godzilla [ICG May 2014] and Big Eyes [ICG December 2014] all shot Vancouver for San Francisco, and Adaline followed suit. “Lee pushed to shoot the whole film in San Francisco,” Lanzenberg adds. “But it just wasn’t affordable. In the last 10 years, California has dropped the ball [with film incentives] in my opinion, and a generation of younger crew people may miss the opportunity of being trained by the older guys if Hollywood keeps losing shows. Vancouver-for-San-Francisco can work, but you spend money on CG and set dressing to get it looking as much like the city as possible. We were fortunate our production designer Claude Paré was on the first Apes film, and our key grip [Finn King] had done Big Eyes, so they were both familiar with the issues.”

After shot-listing the film in its entirety and locking in locations, the duo travelled north to photo-board the feature. “Using our 5Ds, which had ground glass marked for the 2.4 aspect ratio, we took stills of every setup,” Krieger reports. “My fiancée stood in for Adaline, and some PA’s acted as the other characters. We printed those stills on pinup boards and put them up in the production office so the whole movie was laid out two weeks before shooting.”

While they were committed to shooting 4K RAW and anamorphic on ALEXA, Lakeshore was adamant about using a RED camera. “They hadn’t done anything fully anamorphic and wanted us to use the Epic,” Lanzenberg recalls. “We did a lot of testing on Red and found Dragon to be far more sophisticated than Epic. But it read more like a 300-speed camera than an 800-speed. We had to push a ton of light through, which meant having to use 20K or 10K units instead of 5Ks. That can explode a lighting budget, so when I was asked, ‘Do you really need that lighting balloon?’ I would say, ‘With this camera, yes.’ But cinematographers should be able to work with any camera, so we shot it using many different kinds of glass to keep from getting that severe HD crispness I feared. We were able to go anamorphic for the contemporary scenes.”

Preferring the visual dialog offered by prime lenses, Lanzenberg relied upon Hawk’s anamorphic V-Series and V-Lites. “The Hawks were a little more clinical in look,” he relates, “working well with the more contrasty modern-day tones.” Though the DP had to resort to shooting wide open on a few occasions, he was able to maintain a stop between 2.8 and 3.5 for most of production.

For scenes set in the 1960s, Kowa anamorphics – rehoused by Clairmont – were employed. “Their warmth and softness worked very well for that section of her story,” Lanzenberg describes. “Then we had Bausch and Lomb Super Baltars for the pre-forties era, which was shot spherical. They had their own nice quality, a great falloff on the frame edges, because the Dragon’s large sensor would see irregularities in the glass in an unusual way – the lenses were never designed to be used with such a large gate or sensor. DIT James Notari and I built some looks during prep, which were like a different film stock for each time period.”

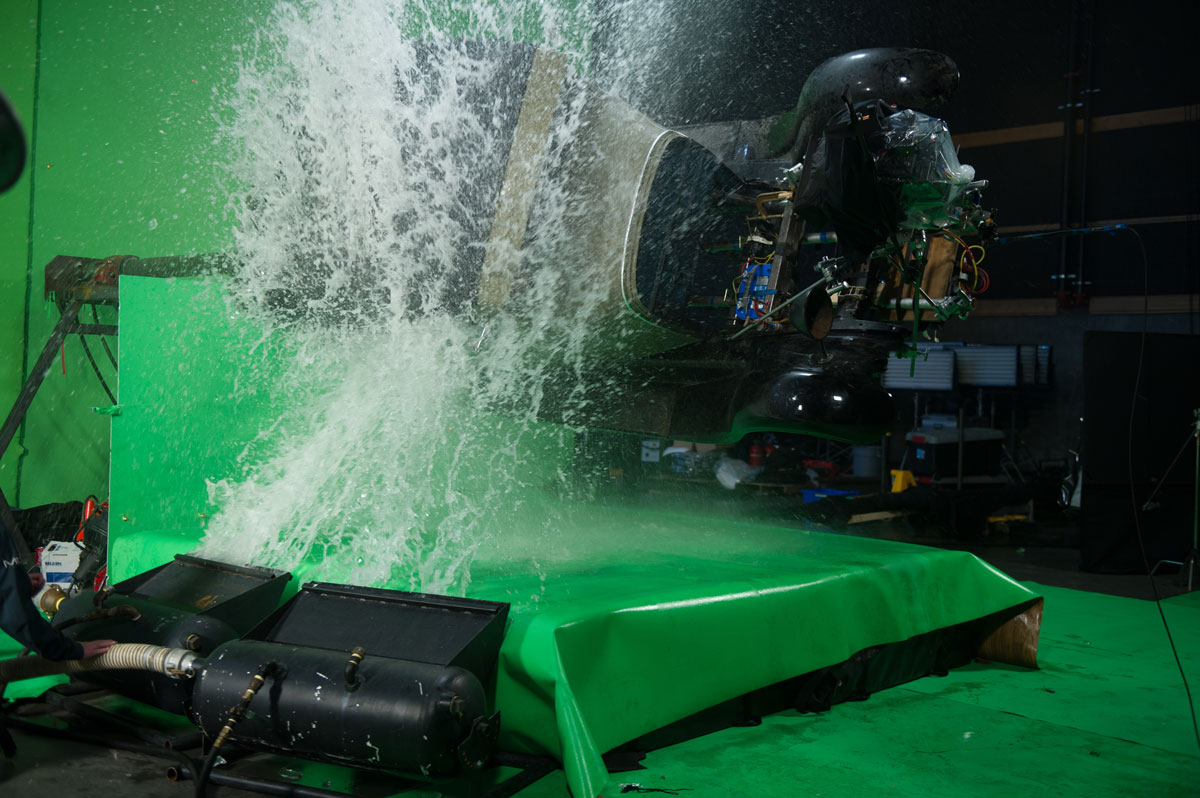

Adaline’s immortality begins in the 1920s, and as Lanzenberg wryly observes, “she is a terrible driver, winding up in accidents at both the beginning and end of the film. For the first one, she is driving a Model-A that ends up in a pond. We shot in March, when there are very low temperatures and various restrictions in Canada, so our production designer built this amazing set on stage with the car leaning on its side.”

Two tanks were employed for the sinking vehicle, one for everything shot above the waterline, the other for underwater views. “The second was a 35-foot tank, maybe twenty feet deep,” the DP adds. “We had a 4K Phantom camera for that to capture anything going on underwater.”

For the night driving scenes preceding the crash, an age-old issue reared its head. “How do you light a night scene on a road that has no street lamps [as motivation]?” asks Lanzenberg. “In our case, that meant four 135-foot Condors at each edge of the road, all pushing Maxis. How do you justify light coming from everywhere? We were helped by the fact there is a very surreal aspect to this movie, so claiming this is moonlight makes sense, and it looked beautiful with some depth. Arc lights would have been even more fitting had they been available.”

Discussions with Gaffer Dave Tickell and Key Grip Finn King followed the Lanzenberg/Krieger plan to keep things more classical in feel. Daytime scenes, which included many tight practical locations, were accomplished with minimal HMI and bounce lighting, using small controllable units whenever possible.

“We had several Chimeras with the hard honeycomb crates, along with Crone cones with either 30-degree and 90-degree crates attached to Tweenie 650-watt or open-face units,” states Lanzenberg, “to keep the light soft and directional.”

Driving scenes relied upon poor man’s process, but the director’s critical eye impacted how the plate work was recorded. “The defocusing properties of anamorphic lenses differ from spherical ones,” observes Krieger, “which affected how we achieved composite shots. I hate seeing poor-man’s stuff where the plate is shot spherical at a deep stop but then gets defocused in post – the out-of-focus bits don’t have that distinctive almond shape. David and I shot our own plates whenever possible, but when we didn’t, we made sure it looked like we did.”

Toward this end, they made good use of Lakeshore’s jack-of-all-trades, James McQuaide. “Working as both VFX supervisor and second unit director seems a very natural marriage,” reflects McQuaide. “On effects-driven pictures, I find it easier to direct plates required for a particular shot rather than explain what’s needed [and why] to someone else. One challenge of this picture, given its tone and style, was that VFX shots really did need to be invisible, as if they had been photographed practically. The falling snow, the San Francisco set extensions and even the car comps had to seem almost mundanely real to go unnoticed; there was none of the usual wiggle room you typically have on a genre picture where spectacle is nearly as important as photo-realism.”

The VFX professional’s history with primary vendor Luma [see Invisible VFX, ICG April 2011] spans two-dozen projects and goes back to his first-ever supervisory gig. “Luma handled the first car crash [including the falling snow] as well as all three ‘celestial’ sequences in the picture,” McQuaide reveals. “Aesthetically, these space shots proved a challenge, since there isn’t any reference to draw from – no one has witnessed these events from [this] perspective.” Those include views of Earth from space that bookend the film, along with a passing comet and an asteroid that strikes the moon.

Australian VFX facility Cutting Edge was also used. McQuaide describes the company as “very filmmaker friendly” and obsessive about delivering on time and on budget. “It was an extremely efficient workflow – by the time their day begins, I’ve had hours to review work from the previous night,” he adds. Among other duties, Cutting Edge was responsible for compositing San Francisco cityscapes into Vancouver live-action.

“From a technical perspective, the use of Hawk V-Lite anamorphic lenses proved a much greater challenge than expected,” McQuaide adds. “Because these lenses so significantly vignette and distort the image, even simple comping required a great deal of ‘hunting and pecking.’”

Adaline’s digital intermediate proved fairly straightforward, with Company3’s Stephan Nakamura handling colorist duties. “It was mostly just a matter of tweaks, Krieger states. “We did have to make more adjustments on skin tones than we might have with Alexa, but it didn’t slow things down excessively. I think the heavy prep we did also helped us as we weren’t having to look for answers after the fact; I’m going to want to do that on every movie from now on.”

Lanzenberg concludes by describing Adaline as “a fantastic experience and another great collaboration with Lee. Most of all, I’m very proud of how well we all managed to stay on the same page creatively while telling this story.”