Pete Kozachik, ASC, was that rare filmmaker whose creativity and technical knowledge matched a drive for innovative storytelling.

by Jimmy Matlosz / Photos Courtesy of Katy Kozachik/Anthony Scott

I met Pete Kozachik, ASC, (a 30-year member of this Guild) when he hired me as an AC for Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas. To say I was lucky to work on a film with such artistry and staying power, under such a gifted gentleman (and me only three years out of college), is an understatement. Pete set the bar so high for creativity, humanity, and professionalism that many of us have spent the better part of our careers honoring him. Sadly, he left us on September 12, 2023, at the age of 72, after a 12-year battle with primary progressive aphasia. When the news was released, a collective sigh could be felt far and wide by hundreds of his collaborators.

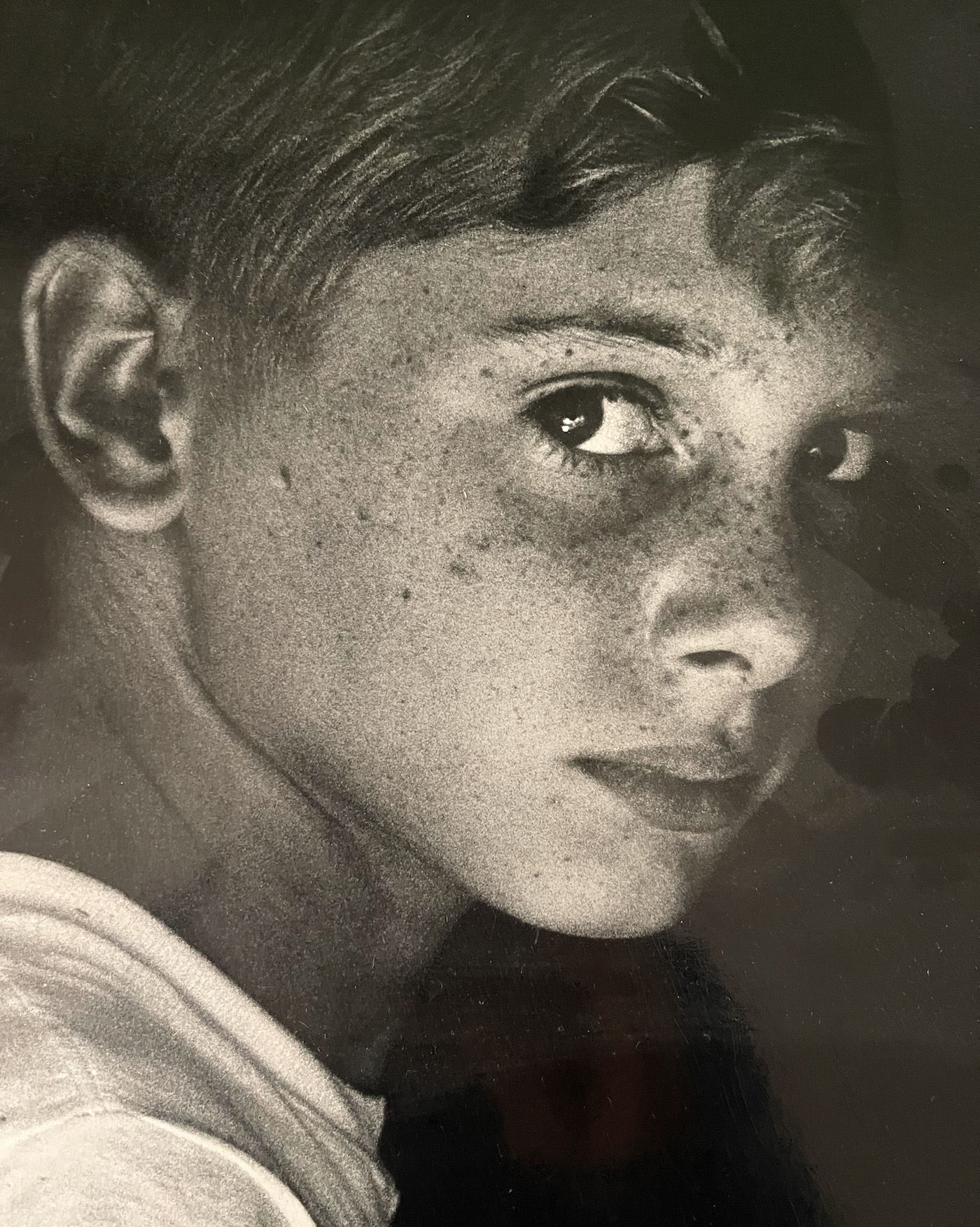

Pete started life in Michigan on March 28, 1951. In the summer of 1958, a seven-year-old Pete was mesmerized by a film that would go on to influence a generation of visual effects professionals – The 7th Voyage of Sinbad. His mother, seeing her son’s curiosity, planted a seed that would sprout into a lifetime of creative achievement, asking the curious youngster if he thought the monsters he was seeing were robots. Months later, when Pete saw King Kong for the first time, he kept a keen eye on the moving monsters, recognizing it was the first time he’d noticed a movie having a “look.”In third grade, the budding filmmaker spent hours at the newsstand studying magazines and comic books, including the highly influential Famous Monsters of Filmland, which offered the first hint that movies were made by regular people. Digging deeper, he discovered photos of Ray Harryhausen with the Cyclops and dragon from The 7th Voyage of Sinbad. By 1963, at the age of twelve, Pete had invested much of his free time into learning photography and how to make puppets, setting himself up to make his own stop-motion animated dinosaur film in his backyard.

Pete spent a few days repositioning and filming his homemade puppets frame by frame. When finished, he projected his masterpiece and marveled that it was “jerky and halting. But it was alive!” Encouraged, he made another animated short with a Kong and the Allosaurus in his bedroom, learning two important lessons from that experience. One was that he needed to estimate how many frames movement should take, and the other was that he needed a light meter. Going big for his next project, Pete tried a remake of King Kong on 8-millimeter black-and-white film. He petitioned his English teacher to count the film as an assignment and recruited classmates to act, using double exposures to place the actors and animated puppets in the same scene. Over a year later, the film was finished complete with Kong atop the Empire State Building battling biplanes. Pete was 13 years old.

In 1967, Pete’s mother moved the family to Tucson, Arizona – a key event for a promising filmmaker who was now much closer to Hollywood. At the ripe age of 15, Pete sought out film studios in the area and landed on Aztec Studios, where he shared his King Kong film, earning kudos from the filmmakers.

After graduating from the University of Arizona with a degree in engineering and physics in 1974, Pete secured his first job as a middle school science teacher, but that path was never in the cards. Motivated to be a filmmaker, he convinced Tucson TV station KZAZ (the smallest independent station in the country) to hire him (at half the salary of his teaching job). Before long, Pete rose to the roles of technical director and on-air director, calling the shots for news, live shows, church shows, and professional wrestling. He dabbled in commercials and station ID’s with his animation talents and soon made station ID’s. In 1976, just two years out of college, he started his own animation business and lensed local commercials for radio stations and car washes, injecting an animated giant ape or dinosaur whenever possible.

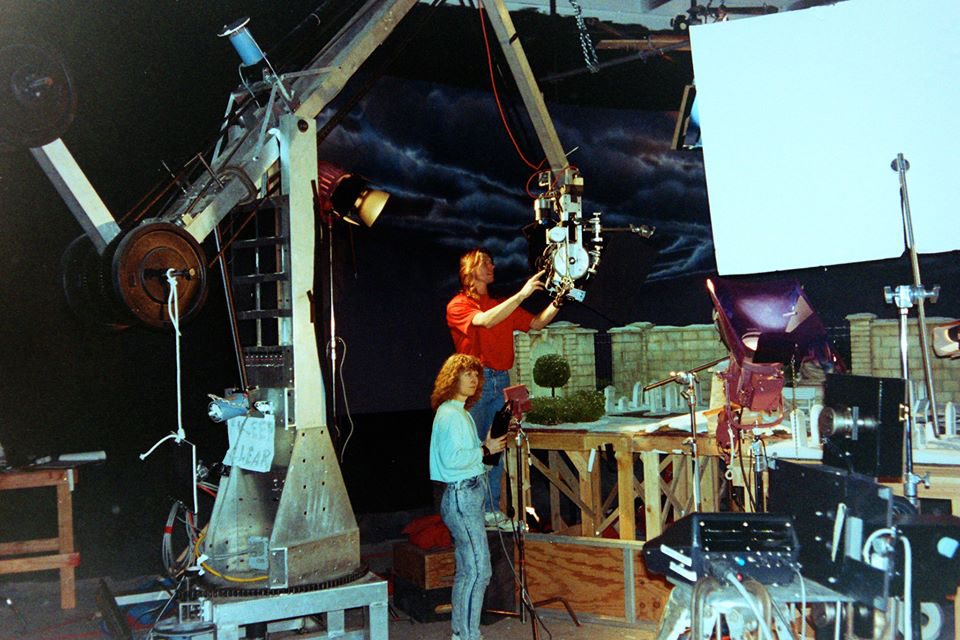

Venturing off to Hollywood with his nine-minute film reel of commercials and station ID’s, Pete focused his sights on established VFX studios. He found opportunities at Coast FX, Excelsior! Animated Moving Pictures and Introvision. These opportunities offered a glimpse of the new motion-control rigs used in the burgeoning VFX field. His first job was at Excelsior!, where he learned the realities of entry-level film work included cleaning up the sidewalk in front of the Hollywood studio for a visiting VIP. In Hollywood, Pete learned to work with bigger crews on bigger projects – as a puppet maker, animator, AC, and camera operator – earning his education on multi-day stop-motion or effects sequences where crews would struggle to stay awake to avoid costly mistakes.

Eager to spread his wings, he set his sights on a then-burgeoning VFX house called Industrial Light & Magic (ILM), where a recommendation found him working alongside Star Wars legends Dennis Murren and Ken Ralston and starting as an AC to effects camera operator Pat Sweeney. Pete’s time at ILM saw him working on Howard the Duck, Innerspace and Star Trek: The Voyage Home. When he left ILM, he landed at Colossal Pictures, where he met Director Henry Selick, who was seeking someone with Pete’s skills and enthusiasm for his MTV pilot, Slow Bob in the Lower Dimensions. When the show was not picked up, Kozachik was recruited by legendary ILM animator Phil Tippett to work with him on a new dinosaur film for Steven Spielberg.

Meanwhile, across town, Selick was developing his own project with Tim Burton. They invited Pete to an informal meeting, at which Burton agreed Pete would be a great director of photography for The Nightmare Before Christmas. In the foreword of Kozachik’s autobiography, Tales From the Pumpkin King’s Cameraman, Burton praised the cinematographer. “It takes an unusual person to work in stop-motion: Imagine patience, technical ability, and a strong artistic vision – Pete’s style gives you an insight into this special world and the weirdness, excitement, depression, humor, anger, loneliness, and creativity of it all.”

Although helming an entire stop-motion feature film was enticing, the uncertainty of an experimental movie with no script and a first-time director was a long shot compared to the opportunity to fulfill a lifelong dream of animating dinosaurs for Steven Spielberg. But, ultimately, the experimental stop-motion movie won out and the animated dinosaurs were rendered to computers. As Sweeney (Kozachik’s first hire on Nightmare) reflects, “Pete trusted his camera people. We were free to express our creativity within the constraints of the movie. I did a shot with Lock, Shock, and Barrel in their clubhouse pushing Santa Claus down a tube to Oogie Boogie’s lair. After the scene was animated, I asked Pete if he was going to add flames in post to the candles. He shocked me by telling me to rewind the film – containing two weeks of precious frame-by-frame animation – light the candles, and shoot them close to real time. Shouldering the responsibility for this in-camera effect on a tight schedule, Pete believed we could pull it off. He brought the best out of everyone.”

Here are Selick’s thoughts on his collaborator: “Pete was a totally hands-on guy, who reinvented what stop-motion animation could be, building motion-control rigs to fly those old Mitchell cameras around Jack Skellington – whom he called ‘that dorky skeleton’ – lighting shots like Vittorio Storarro, doing in-camera effects shots that got him nominated for an Oscar, leading, and lifting his lighting team to a level of excellence no one could have imagined. He worked his ass off, never raised his voice, and cracked me up with a fake machismo act. Yes, he was utterly normal looking but was actually a wonderfully weird, super talented artist with an incredible eye, always a pleasure to work with and completely reliable. I’d like to think I helped launch his career; I know he made my handful of features infinitely better than they would have been without him.”

What’s This was the first sequence filmed (without a script), and it took over six weeks to film, which was oddly motivating for Kozachik. He would be putting every bit of his years in the trenches to the test. As Art Director Deane Taylor reflects: “Everything Pete did was calculated spontaneity fueled by genuine talent. As a result, when it came to meetings around shot setups, I made sure to keep my mouth shut until Pete had constructed the scaffold of the shot. At that time, we could all then climb over and add notes to enhance the shot.”

Kozachik was managing eight camera teams, delving into management, and reading books about making films. The Nightmare Before Christmas took almost three years to complete, earned him a VFX Academy Award nomination, and cemented his name in filmmaking history. (Pete also got the cover story in the December 1993 issue of American Cinematographer.)

Selick and Kozachik reunited for James and the Giant Peach, continuing to push the filmmaking limits with computer-based VFX. As Peach ended, Kozachik jumped at the opportunity to work on Starship Troopers as a motion-control camera operator. It was a chance to shoot some of the last model spaceships before CGI took over. When Trooperswrapped, Kozachik returned to his role as cinematographer with the live-action/stop-motion picture Monkey Bone, directed by Selick. Their challenge was to work with live-action and animation crews to ensure a seamless blend of the two disciplines. Soon after wrap, he returned as a VFX camera operator on Star Wars: Episode II – Attack of the Clones, reuniting him with Sweeney and a handful of Nightmare alumni.

More importantly, at the company Christmas party, Pete, the odd man out since his fellow VFX compadres didn’t attend, met his future wife – painter and art teacher Professor Katy Moore. The pair danced the night away and were married shortly after. Wanting to stay in the Bay Area, Pete took the job of VFX camera operator for the Matrix sequels, where he and his team built and operated the largest motion-control rig to date, outfitted with a 30-foot extension arm, attached to an old gantry mounted in hanger rafters and parked level of 21 feet overhead.

When stop-motion came knocking again, it was director Mike Johnson, an alumnus from Nightmare who teamed up with Burton to bring Corpse Bride to life. Kozachik had to interview for the project, which had a budget only slightly more than Nightmare and was slated to be filmed in England. Convincing the producers he was the right DP, Pete flew off to England with more than 25 Mitchell film cameras and a handful of his custom MoCo rigs. During pre-production, they were faced with the question of why they weren’t shooting digitally. After many tests in a short amount of time, Corpse Bride flipped to all-digital capture, utilizing Canon DSLR cameras, with Pete calling the results “stunning.”

Of Kozachik, Johnson states, “Pete’s love of stop-motion was inspiring. He faced seemingly impossible technical challenges with calm, dry wit, and artistic creativity. On Nightmare, he brought life and fluidity to the camera that had never been seen in stop-motion before. On Corpse Bride, Pete went out on a limb by convincing Warner Bros. that we could achieve rich, cinematic visuals using the new and unproven technology of digital cameras for the first time in a stop-motion feature film. Pete was a great artist and technician, a kind-hearted, sharp-witted perfectionist. He gave so much to the world of stop-motion and VFX, and his spirit lives on in his films.”

In fact, Selick was unsure if digital capture was the way to go, and Kozachik assured him it was. That may be why their next film together, Coraline, ventured to take a deep dive into 3D digital technology. Exercises in interocular and convergence were new challenges for both filmmakers and animators. Where do you place the lens when your puppet’s eyes are centimeters, yet the human eye is measured in inches? There would be an increasing reliance on post-FX and less on the practical. The film was a triumph for both men, landing the rank of the third-highest-grossing stop-motion film of all time. Kozachik praised his crew for delivering one of the most technically challenging and ambitious stop-motion films to date. When Coraline wrapped, Pete had no idea it would be his last film.

Shortly after settling in at home, Kozachik set about pursuing a childhood dream: to build and fly his own plane (which he did successfully). However, a few tongue-tied moments and confusion of terms led to a doctor’s visit and the diagnosis that would ultimately silence this gifted artisan. In his biography, Tales from the Pumpkin King’s Cameraman, penned by Pete and his wife Katy over the following decade, fans get a glimpse into the wonderment and innocence of discovery that Kozachik brought to his life’s work.

For me, it’s difficult closing the book on this talented mentor, happy-go-lucky genius, and friend, whose career was blessed with daunting technical challenges that he embraced with such enthusiasm as to invite a greater peak to scale each time. I’ll leave ICG readers with the words of Pete’s friends and fellow VFX professionals.

“The term ‘wizard’ gets thrown around a lot in our industry,” states Eric Swensen. “But in all my years, there has been only one that I have ever known that personified that moniker, the rare human Pete Kozachik.”

“The thing about Pete that I really appreciated was that he was always curious,” adds nine-time Oscar-winner Dennis Murren. “He would look at the situation and he would think about it quietly, and come at it with a very mechanical understanding.

“Pete was a dedicated and talented cameraman who was an expert in [filmmaking] tools and creating the images. Always looking ahead as a way of doing something better or more precisely. Nightmare was a revelation… amazing, the work and discipline and continuity, the way Pete set it up and not taking no for an answer, creating great camera moves and lighting. I think it was pretty mind-blowing that he offered Nightmare a cinematic point of view with a moving camera for the first time.”